world.wikisort.org - USA

Winston-Salem is a city and the county seat of Forsyth County, North Carolina, United States.[4] In 2020, the population was 249,545, making it the second-largest municipality in the Piedmont Triad region, the 5th most populous city in North Carolina, the third-largest urban area in North Carolina, and the 90th most populous city in the United States.[5] With a metropolitan population of 679,948 it is the fourth largest metropolitan area in North Carolina. Winston-Salem is home to the tallest office building in the region, 100 North Main Street, formerly known as the Wachovia Building and now known locally as the Wells Fargo Center.

Winston-Salem, North Carolina | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Winston-Salem | |

Skyline of Winston-Salem with the redeveloped Bailey Power Plant in the foreground and 100 North Main Street, Winston Tower, and the Reynolds Building in the background | |

Flag  Seal  Logo | |

| Nickname(s): Twin City, Winston, W-S, The Dash City, The 336 | |

| Motto: "Urbs Condita Adiuvando" (A city founded on cooperation) | |

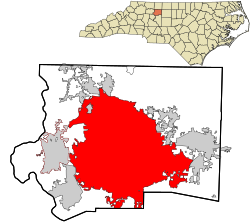

Location in Forsyth County and the state of North Carolina. | |

Winston-Salem, North Carolina Location in the contiguous United States | |

| Coordinates: 36°6′9.95″N 80°15′37.77″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | North Carolina |

| Counties | Forsyth County |

| Founded | 1766 (Salem), 1849 (Winston) |

| Consolidated | 1913 (Winston-Salem) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Allen Joines (D)[1] |

| • City Manager | Lee D. Garrity [2] |

| Area | |

| • City | 134.74 sq mi (348.98 km2) |

| • Land | 133.53 sq mi (345.84 km2) |

| • Water | 1.21 sq mi (3.14 km2) |

| Elevation | 970 ft (300 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 249,545 |

| • Rank | 5th in North Carolina 89th in United States |

| • Density | 1,868.82/sq mi (721.55/km2) |

| • Urban | 391,204 (US: 96th) |

| • Metro | 10 (US: 88th) |

| • CSA | 1,699,123 (US: 36th) |

| Demonym | Winston-Salemite |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 27023, 27040, 27045, 27101-27110, 27113-27117, 27120, 27127, 27130, 27150, 27152, 27155, 27157, 27198-27199, 27284 |

| Area code | 336/743 |

| FIPS code | 37-75000 |

| Primary Airport | Piedmont Triad International Airport |

| Interstates |

|

| U.S. Routes |

|

| Website | www |

In 2003, the Greensboro-Winston-Salem-High Point metropolitan statistical area was redefined by the OMB and separated into the two major metropolitan areas of Winston-Salem and Greensboro-High Point. The population of the Winston-Salem metropolitan area in 2020 was 679,948. The metro area covers over 2,000 square miles and spans the five counties of Forsyth, Davidson, Stokes, Davie, and Yadkin.

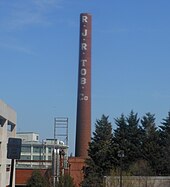

Winston-Salem is called the "Twin City" for its dual heritage, and "the Camel City" is a reference to the city's historic involvement in the tobacco industry related to locally based R.J. Reynolds' Camel cigarettes. Many natives of the city and North Carolina refer to the city as "Winston" in informal speech. Winston-Salem is also home to six colleges and institutions, most notably Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem State University, and the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, which ranks as one of the best arts schools in America. In 2021, the city ranked No. 46 out of 150 cities on the "Best Places to Live" list from U.S. News & World Report. In April 2021, a study from Lendingtree's Magnify Money blog ranked Winston-Salem the second-best tech market for women.[6]

History

The city of Winston-Salem is a product of the merging of the two neighboring towns of Winston and Salem in 1913.

Salem

The origin of the town of Salem dates to January 1753, when Bishop August Gottlieb Spangenberg, on behalf of the Moravian Church, selected a settlement site in the three forks of Muddy Creek. He called this area "die Wachau" (Latin form: Wachovia) after the ancestral estate of Count Nicolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf. The land, just short of 99,000 acres (400 km2), was subsequently purchased from John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville.

On November 17, 1753, the first settlers arrived at what would later become the town of Bethabara. This town, despite its rapid growth, was not designed to be the primary settlement on the tract. Some residents expanded to a nearby settlement called Bethania in 1759. Finally, lots were drawn to select among suitable sites for the location of a new town.

The town established on the chosen site was given the name of Salem (from "Shalom", meaning "Peace", after the Canaanite city mentioned in the Book of Genesis) chosen for it by the Moravians' late patron, Count Zinzendorf. On January 6, 1766, the first tree was felled for the building of Salem. Salem was a typical Moravian settlement congregation with the public buildings of the congregation grouped around a central square, today Salem Square. These included the church, a Brethren's House and a Sisters' House for the unmarried members of the Congregation, which owned all the property in town. For many years only members of the Moravian Church were permitted to live in the settlement. This practice had ended by the American Civil War. Many of the original buildings in the settlement have been restored or rebuilt and are now part of Old Salem Museums & Gardens.[7]

Salem was incorporated as a town in December 1856.[8] Salem Square and "God's Acre", the Moravian Graveyard, since 1772 are the site each Easter morning of the Moravian sunrise service. This service, sponsored by all the Moravian church parishes in the city, attracts thousands of worshipers each year.[9]

Winston

In 1849, the Salem Congregation sold land north of Salem to the newly formed Forsyth County for a county seat. The new town was called "the county town" or Salem until 1851, when it was renamed Winston for a local hero of the Revolutionary War, Joseph Winston.[10] For its first two decades, Winston was a sleepy county town. In 1868, work began by Salem and Winston business leaders to connect the town to the North Carolina Railroad.[11] That same year, Thomas Jethro Brown of Davie County rented a former livery stable and established the first tobacco warehouse in Winston. That same year, Pleasant Henderson Hanes, also of Davie, built his first tobacco factory a few feet from Brown's warehouse. In 1875, Richard Joshua Reynolds, of Patrick County, Virginia, built his first tobacco factory a few hundred feet from Hanes' factory. By the 1880s, there were almost 40 tobacco factories in the town of Winston. Hanes and Reynolds would compete fiercely for the next 25 years, each absorbing a number of the smaller manufacturers, until Hanes sold out to Reynolds in 1900 to begin a second career in textiles.[citation needed]

Winston-Salem

In the 1880s, the US Post Office began referring to the two towns as Winston-Salem. In 1899, after nearly a decade of contention, the United States Post Office Department established the Winston-Salem post office in Winston, with the former Salem office serving as a branch. After a referendum the towns were officially incorporated as "Winston-Salem" in 1913. Robert Gray was the first to mention the two towns as one as a featured speaker at the 1876 centennial celebration.

The Reynolds family, namesake of the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, played a large role in the history and public life of Winston-Salem. By the 1940s, 60% of Winston-Salem workers worked either for Reynolds or in the Hanes textile factories.[12] The Reynolds company imported so much French cigarette paper and Turkish tobacco for Camel cigarettes that Winston-Salem was designated by the United States federal government as an official port of entry for the United States, despite the city being 200 miles (320 km) inland.[12] Winston-Salem was the eighth-largest port of entry in the United States by 1916.[12]

In 1917, the Reynolds company bought 84 acres (340,000 m2) of property in Winston-Salem and built 180 houses that it sold at cost to workers, to form a development called "Reynoldstown."[12] By the time R.J. Reynolds died in 1918, his company owned 121 buildings in Winston-Salem.[12]

In 1920, with a population of 48,395, Winston-Salem was the largest city in North Carolina.[13][14][15]

In 1929, the Reynolds Building was completed in Winston-Salem. Designed by William F. Lamb from the architectural firm Shreve, Lamb and Harmon, the Reynolds Building is a 314 feet (96 m) skyscraper that has 21 floors.[16][17] When completed as the headquarters of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, it was the tallest building in the United States south of Baltimore, Maryland, and it was named the best building of the year by the American Institute of Architects.[18] The building is well known for being the predecessor and prototype for the much larger Empire State Building that was built in 1931 in New York City.[19] In 1892, Simon Green Atkins founded Slater Industrial Academy, which later became Winston-Salem State University, a public HBCU University.[20] In 1956, Wake Forest College, now known as Wake Forest University would move to Winston-Salem from its original location in Wake Forest, North Carolina.[21]

Notable early businesses

- In 1799, the Winkler Bakery, famous for its Moravian cookies, was commissioned, and in 1807, the congregation brought in Christian Winkler of Pennsylvania to operate the bakery; his family owned and operated the business until 1929. It continues to operate today as part of Old Salem.

- In 1875, R J Reynolds founded R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company later famous for branded products such as Prince Albert pipe tobacco (1907) and Camel cigarettes (1913). Other brands which it made famous are Winston, Salem, Doral, and Eclipse cigarettes. The Winston-Salem area is still the primary international manufacturing center for Reynolds brands of cigarettes, although employment is down from its peak of nearly 30,000 to under 3,000.

- In 1901, J. Wesley Hanes's Shamrock Hosiery Mills in Winston-Salem began making men's socks. Shortly afterward, his brother Pleasant Henderson Hanes founded the P.H. Hanes Knitting Company, which manufactured men's underwear. The two firms eventually merged to become the Hanes Corporation, now known as Hanesbrands, innovators in the textile industry.

- In 1906, the Bennett Bottling Company produced Bennett's Cola, a "Fine Carbonic Drink." The name was changed to Winston-Salem Bottling Works in 1915.

- In 1911, Wachovia Bank and Trust was formed by the merger of Wachovia National Bank (founded in 1879 by James Alexander Gray and William Lemly) and Wachovia Loan and Trust (founded 1893). The company was purchased by First Union in 2001, which changed its name to Wachovia. Wachovia was purchased by Wells Fargo in 2009, and the Wachovia name was retired in 2011.[22]

- In 1928, Miller's Clothing Store was opened by Mrs. Henry Miller. Miller's Variety Store operated at the same location at 622 North Trade Street until closing at the end of 2016.[23] Miller's was the first store in Winston-Salem to offer bell-bottoms in the area in the 1960s. Millers was listed by Playboy magazine in 1968 as a popular place to shop.[24]

- In 1929, the local T.W. Garner Foods introduced Texas Pete, a popular hot sauce.[25]

- In 1929 Quality Oil Company was organized in December 1929, initially to launch a distributorship for the then little known Shell Oil Company.

- In 1934, Malcolm Purcell McLean formed McLean Trucking Co. The firm benefited from the tobacco and textile industry headquartered in Winston-Salem, and became the second largest trucking firm in the nation.[26]

- In 1937, Krispy Kreme opened its first doughnut shop on South Main Street.[27]

- In 1945 Piedmont Bible College opened (now Carolina University).[28]

- In 1948, Piedmont Airlines was formed out of the old Camel City Flying Service. The airline was based at Smith Reynolds Airport in Winston-Salem but marked its first commercial flight out of Wilmington, North Carolina on February 20, 1948. Piedmont grew to become one of the top airlines in the country before its purchase by USAir (later US Airways, merged with American Airlines in 2015) in 1987. American Airlines maintains a reservation center in the old Piedmont Reservations office.

Government

Local government

The governing body for the City of Winston-Salem is an eight-member City Council. Voters go to the polls every four years in November to elect the Mayor and Council. The Mayor is elected at large and council members are elected by citizens in each of the eight wards within the city. The City Council is responsible for adopting and providing for all ordinances, rules and regulations as necessary for the general welfare of the city. It approves the city budget and sets property taxes and user fees. The Council appoints the City Manager and City Attorney and approves appointments to city boards and commissions.[29]

As of September 2020[update], the mayor of Winston-Salem was Allen Joines (D), who was first elected in 2001 and is longest-serving mayor in the history of the city.[30] The members of the City Council were Mayor Pro Tempore Denise Adams (North Ward), Barbara Hanes Burke (Northeast Ward), Annette Scippio (East Ward), James Taylor, Jr. (Southeast Ward), John Larson (South Ward), Kevin Mundy (Southwest Ward), Robert Clark (West Ward), Jeff MacIntosh (Northwest Ward).

City officials appointed by the City Council included City Attorney Angela Carmon and City Manager Lee Garrity.[31]

Emergency Services

This section does not cite any sources. (November 2022) |

The city of Winston-Salem is patrolled by the Winston-Salem Police Department, and the Chief of Police is Catrina A. Thompson. The city is provided fire protection by the Winston-Salem Fire Department, and the Chief of the Department is Trey Mayo.

Geography

Winston-Salem is in the northwest Piedmont area of North Carolina, situated 65 miles (105 km) northwest of the geographic center of the state. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 133.7 square miles (346.3 km2), of which 132.4 square miles (343.0 km2) is land and 1.2 square miles (3.2 km2), or 0.93%, is water.[32] The city lies within the Yadkin–Pee Dee River Basin, mainly draining via Salem Creek, Peters Creek, Silas Creek, and Muddy Creek.

Less than 30 miles (48 km) north of Winston-Salem are the remains of the ancient Sauratown Mountains, named for the Saura people who lived in much of the Piedmont area, including what is now Winston-Salem.[33]

Winston-Salem is located 16.66 miles northwest of High Point,[34] 25.32 miles west of Greensboro,[35] 69.04 miles northeast of Charlotte,[36] and 80.20 miles east of Boone.

Neighborhoods and areas

The City of Winston-Salem consists of 66 constituent neighborhoods and covers 25 zip codes and a total area of 133.8 square miles. Winston-Salem is the 72nd largest city by area in the United States and the fourth-largest community in North Carolina.

Downtown

Downtown, the central business district of Winston-Salem, is the largest in the Piedmont Triad region. With a population of approximately 14,000 and a workforce of over 27,000, downtown Winston-Salem is a hotspot for growth. Fourth Street, the "main drag" consists of bars, restaurants, retail, hotels, and luxury residential units. The area is surrounded by Northwest Boulevard to the north and west, Salem Parkway to the south, U.S. Route 52 to the east. Downtown features major attractions such as Innovation Quarter, Truist Stadium, Old Salem and Benton Convention Center.

West End

One of the most notable neighborhoods in the city, West End, features the West End Historic District which covers an area of 229 acres and predominantly residential. Most of the buildings in West End were built between 1887 and 1930. Major thoroughfares in West End are West End Boulevard, Northwest Boulevard, and First Street that all lead to downtown Winston-Salem. The neighborhood offers an urban lifestyle with shops, parks, restaurants, and services all being located within the area.

Ardmore

Ardmore, one of the largest neighborhoods in Winston-Salem features Ardmore Historic District which contains over 2,000 buildings and two sites. Ardmore is near Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center which is the second largest hospital in North Carolina. Wake Forest Baptist Health is the largest employer in Forsyth County with over 13,000 employees and serves North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and South Carolina. Major thoroughfares in Ardmore are South Hawthorne Road, Miller Street, Cloverdale Avenue, and Queen Street.[37]

Buena Vista

Sitting northwest of downtown, the neighborhood is in close proximity to a wide range of activities and services such as the Reynolda House and Reynolda Gardens. It is known around Winston-Salem for its quiet tree-lined streets that give it an "exclusive" feel. About ten minutes from downtown and five minutes from one of the city's upscale shopping centers, Thruway. The Thruway Center features national chains such as Trader Joe's, Athleta, and J.Crew. Most homes in Buena Vista cost between $600,000 to several million dollars.[38]

Hanes Mall Boulevard/Stratford Road

Located seven miles southwest of downtown is the busiest shopping district in Winston-Salem and Forsyth County. The corridor has a variety of national retailers like Target, Costco, and Ethan Allen. Two major companies, Novant Health and Truliant Federal Credit Union call the boulevard home. The intersection of Hanes Mall Boulevard and Stratford Road is the second-busiest intersection in Winston-Salem, with an average daily traffic count of 54,000.[39]

North Winston

North Winston is located three miles northeast of downtown, with Patterson Avenue running north to south and 25th Street serves as the east-west thoroughfare. The area is bound by University Parkway to the west and U.S. Route 52 to the east, stretching from 13th Street to 30th Street.

University area

The university area is situated in the north-central and northwestern sections of the city. University Parkway, the 4-8 lane boulevard named after Wake Forest University serves as the downtown-north connector. Neighborhoods in the area include Alspaugh and Mount Tabor, and contains some of Winston-Salem's busiest throughafares. It is bound by North Point Boulevard to the north, Coliseum Drive to the south, University Parkway to the east, and Silas Creek Parkway and Reynolda Road to the west. Other roads in the area are Polo Road, Reynolds Boulevard, and Deacon Boulevard. Attractions in the area the Winston-Salem Entertainment-Sports Complex which includes LJVM Coliseum, the Winston-Salem Fairgrounds, Winston-Salem Fairgrounds Annex, Truist Field, Truist Stadium, and David F. Couch Ballpark. The Winston-Salem Fairgrounds also host the Carolina Classic Fair, formerly the Dixie Classic Fair. The fair is one of the most visited fairs in North America; the second-most visited in North Carolina, next to the North Carolina State Fair.[40]

Renovations

Community renovations are planned for the corner of Peters Creek Parkway and Academy Street. On September 11, 2018 The Winston-Salem Journal reported that The City of Winston-Salem Committee approved the Peters Creek Community Initiative project, which is a collaboration of The Shalom Project, North Carolina Housing Foundation, and The National Development Council. The group plans to purchase property where the Budget Inn currently stands and build 60 apartment units with a 4,000 square foot community space.[41] PCCI plans to build a four-story building that will house The Shalom Project in the bottom floor, along with other businesses.[42]

Climate

The city of Winston-Salem has a humid subtropical climate characterized by cool winters and hot, humid summers. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is Cfa.[43] The average high temperatures range from 51 °F (11 °C) in the winter to around 89 °F (32 °C) in the summer. The average low temperatures range from 28 °F (−2 °C) in the winter to around 67 °F (19 °C) in the summer.[44]

| Climate data for Winston-Salem, North Carolina Smith Reynolds Airport 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1899–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 79 (26) |

83 (28) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

101 (38) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

96 (36) |

84 (29) |

79 (26) |

104 (40) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 48.8 (9.3) |

52.8 (11.6) |

60.8 (16.0) |

70.6 (21.4) |

77.9 (25.5) |

84.9 (29.4) |

88.0 (31.1) |

86.1 (30.1) |

80.1 (26.7) |

70.6 (21.4) |

60.1 (15.6) |

51.7 (10.9) |

69.4 (20.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 39.8 (4.3) |

43.0 (6.1) |

50.4 (10.2) |

59.4 (15.2) |

67.5 (19.7) |

75.1 (23.9) |

78.6 (25.9) |

77.0 (25.0) |

70.6 (21.4) |

59.9 (15.5) |

49.6 (9.8) |

42.6 (5.9) |

59.5 (15.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 30.7 (−0.7) |

33.2 (0.7) |

40.1 (4.5) |

48.3 (9.1) |

57.0 (13.9) |

65.4 (18.6) |

69.2 (20.7) |

67.9 (19.9) |

61.2 (16.2) |

49.3 (9.6) |

39.1 (3.9) |

33.6 (0.9) |

49.6 (9.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −10 (−23) |

−1 (−18) |

10 (−12) |

21 (−6) |

30 (−1) |

40 (4) |

48 (9) |

47 (8) |

36 (2) |

21 (−6) |

7 (−14) |

−3 (−19) |

−10 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.35 (85) |

3.89 (99) |

3.60 (91) |

3.71 (94) |

3.76 (96) |

3.64 (92) |

4.24 (108) |

4.51 (115) |

3.86 (98) |

3.28 (83) |

3.06 (78) |

3.30 (84) |

43.20 (1,097) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.5 | 9.4 | 11.2 | 10.2 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 11.9 | 11.1 | 10.0 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 9.2 | 125.5 |

| Source: NOAA[45][46] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 443 | — | |

| 1880 | 4,194 | 846.7% | |

| 1890 | 10,729 | 155.8% | |

| 1900 | 13,650 | 27.2% | |

| 1910 | 22,700 | 66.3% | |

| 1920 | 48,395 | 113.2% | |

| 1930 | 75,274 | 55.5% | |

| 1940 | 79,815 | 6.0% | |

| 1950 | 87,881 | 10.1% | |

| 1960 | 111,135 | 26.5% | |

| 1970 | 133,683 | 20.3% | |

| 1980 | 131,885 | −1.3% | |

| 1990 | 143,485 | 8.8% | |

| 2000 | 185,776 | 29.5% | |

| 2010 | 229,617 | 23.6% | |

| 2020 | 249,545 | 8.7% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 250,320 | [47] | 0.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[48] 2020[49] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 109,714 | 43.97% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 79,788 | 31.97% |

| Native American | 607 | 0.24% |

| Asian | 6,275 | 2.51% |

| Pacific Islander | 191 | 0.08% |

| Other/Mixed | 10,129 | 4.06% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 42,841 | 17.17% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 249,545 people, 94,884 households, and 53,708 families residing in the city.

Winston-Salem's population grew by 9.2% from 2010 to 2020,[51] making it the fifth largest city in North Carolina.

2017

As of the estimate of 2017,[52] the population was 244,605, with 94,105 households and a population density of 1,846.08 people per square mile.

Winston-Salem was 53.0% female, and 27.8% of its firms were owned by women. The median age was 35 years. 23.9% of the population was under 18 years old, and 13.7% of the population was 65 years or older.[53]

The racial composition of the city in 2017 was 56.1% White, 34.7% Black or African American, 2.2% Asian American, 0.3% Native American, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific native alone, and 2.3% two or more races. In addition, 14.8% was Hispanic or Latino, of any race. Non-Hispanic Whites were 45.8% of the population in 2017.[54]

38.4% were married couples living together, 17.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.7% were non-families. 33.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 3.06.[55]

The median income for a household in the city was $41,228, and the median income for a family was $53,222. The mean income for a household in the city was $60,637, and the mean income for a family was $74,938. Males had a median income of $41,064 versus $33,683 for females. The per capita income for the city was $24,728. 20.6% of the population and 15.7% of all families were below the poverty line. 26.2% of the total population, 31.6% of those under the age of 18 and 8.2% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[55]

Religion

The city has about 54.14% of the population being religiously affiliated. Christianity is the largest religion, with Baptists (15.77%) making up the largest religious group, followed by Methodists (12.79%) and Catholics (4.39%). Pentecostals (2.97%), Episcopalians (1.3%), Presbyterians (2.59%), Lutherans (0.96%), Latter-Day Saints (0.90%) make up a significant amount of the Christian population as well. The remaining Christian population (11.93%) is affiliated with other churches such as the Moravians and the United Church of Christ. Islam (0.43%) is the second largest religion after Christianity, followed by Judaism (0.20%). Eastern religions (0.02%) make up the religious minority.[56]

The city's long history with the Moravian church has had a lasting cultural effect. The Moravian star is used as the city's official Christmas street decoration. In addition, a 31-foot Moravian star, one of the largest in the world, sits atop the North Tower of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center during the Advent and Christmas seasons.[57] Another star sits under Wake Forest University's Wait Chapel during the Advent and Christmas seasons as well. Also, Moravian star images decorate the lobby of the city's landmark Reynolds Building.

Economy

It is the location of the corporate headquarters of HanesBrands, Inc., Krispy Kreme Doughnuts, Inc., Lowes Foods Stores,[58] ISP Sports, Reynolds American (parent of R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company), Reynolda Manufacturing Solutions, K&W Cafeterias,[59][60] and TW Garner Food Company (makers of Texas Pete).[61] Blue Rhino, the nation's largest propane exchange company and a division of Ferrellgas, is also headquartered in Winston-Salem. Wachovia Corporation was based in Winston-Salem until it merged with First Union Corporation in September 2001; the corporate headquarters of the combined company was located in Charlotte, until it was purchased by Wells Fargo in December 2008. PepsiCo has its Customer Service Center located in Winston-Salem. BB&T was also based in Winston-Salem until it was merged with SunTrust Banks in December 2019; the corporate headquarters of the combined company were relocated to Charlotte.

Although traditionally associated with the textile and tobacco industries, Winston-Salem is transforming itself to be a leader in the nanotech, high-tech and bio-tech fields.[62] Medical research is a fast-growing local industry, and Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center is the largest employer in Winston-Salem. In December 2004, the city entered into a deal with Dell, providing millions of dollars in incentives to build a computer assembly plant nearby in southeastern Forsyth County. Dell closed its Winston-Salem facility in January 2010 due to the poor economy.[63] In January 2015, Herbalife opened a manufacturing facility in the space left vacant by Dell.[64]

Public and private investment of $713 million has created the Wake Forest Innovation Quarter, an innovation district in downtown Winston-Salem which features business, education in biomedical research and engineering, information technology and digital media, as well as public gathering spaces, apartment living, restaurants, and community events.[65]

Largest employers

According to the Winston-Salem Business Inc.'s 2012–2013 data report on major employers,[66] the ten largest employers in the city were:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center | 11,750 |

| 2 | Novant Health | 8,145 |

| 3 | Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools | 6,692 |

| 4 | City/County Government | 4,689 |

| 5 | Reynolds American, Inc. | 3,000 |

| 6 | Wells Fargo | 2,800 |

| 7 | Hanesbrands Inc. | 2,251 |

| 8 | Truist Financial | 2,200 |

| 9 | Wake Forest University | 1,680 |

| 10 | Lowe's Foods | 1,500 |

Major industries

According to the Winston-Salem Business Inc.'s 2012 data report on major industries,[67] the major industries in Winston-Salem/Forsyth County are by percentage:

| # | Employment by Sector | % Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Health Care and Social Assistance | 29% |

| 2 | Trade, Transportation and Utilities | 19% |

| 3 | Professional and Business Services | 14% |

| 4 | Manufacturing | 10% |

| 5 | Leisure and Hospitality | 10% |

| 5 | Financial Activities | 6% |

| 7 | Public Administration | 4% |

| 8 | Construction | 3% |

| 9 | Other Services | 3% |

| 10 | Information | 1% |

Attractions

- Bethabara Historic District is a site where Moravians from Pennsylvania first settled in North Carolina, the 195-acre (0.79 km2) area includes a museum and a Moravian church and offers hiking, birdwatching and many varieties of trees and plants.

- Old Salem is a restored Moravian settlement founded in 1766. Seventy percent of the buildings are original and the village is a living history museum with skilled tinsmiths, blacksmiths, cobblers, gunsmiths, bakers and carpenters practicing their trades while interacting with visitors.[68] Along with the original 18th-century buildings, Old Salem is also home to the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), a gallery of 18th- and early 19th-century furniture, ceramics, and textiles. In addition, Old Salem hosts the Cobblestone Farmers Market every Saturday during the spring season through early autumn.[69] The market is dedicated to providing the public access to sustainably grown food and products.[70]

- Reynolda Gardens is a 4-acre (16,000 m2) formal garden set within a larger woodland site, originally part of the R. J. Reynolds country estate.[71]

- The Wake Forest University Museum of Anthropology is an anthropological museum, maintained by Wake Forest University, that has many artifacts and other pieces of history.

- Kaleideum North (formerly SciWorks) – An interactive museum for children, SciWorks has 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2) of exhibit space, 119-seat Planetarium and 15-acre (61,000 m2) outdoor Environmental Park. Permanent exhibits include: Foucault Pendulum, PhysicsWorks, SoundWorks, HealthWorks, BioWorks and KidsWorks. The Environmental Park includes habitats for river otter, deer and waterfowl.[72]

- Kaleideum Downtown (formerly the Children's Museum of Winston-Salem) offers exhibits and programs designed to develop creative thinking, strengthen language skills, and encourage curiosity for children ages birth to eight. Despite the name, it is primarily an indoor playground for children with activities (admission fee or membership required).[73]

- New Winston Museum is the community history museum for Winston-Salem and Forsyth County. It focuses on time periods since 1850 and features exhibitions and public programs.[74]

- Truist Stadium is a minor league baseball stadium primarily used for baseball with a seating capacity of 5,500. The stadium is located near downtown Winston-Salem and is home to the Winston-Salem Dash. The stadium broke ground in October 2007 and officially opened in April 2010.

- Tanglewood Park is a recreation center in Clemmons, North Carolina located on the Yadkin River between Clemmons and Bermuda Run with a pool, lazy river, tennis courts, and walking trails. Tanglewood Park hosts the Festival of Lights every year. The Festival of Lights is a drive-thru light show that celebrates the holidays. The Festival is ranked as a " Top 100" event in America and a "Top 20" in the southeast.[75]

- Winston-Salem Fairgrounds Annex is an event venue that hosts the Carolina Classic Fair (formerly Dixie Classic Fair) every year in autumn. The fair is located across from the Lawrence Joel Coliseum. In 2007 it had a record-breaking attendance with over 371,000 visitors. This ranked the fair the 50th most attended fair in North America. The Winston-Salem Fairgrounds also holds hundreds of events and has a capacity of 7,000.[76]

- Salem Lake is a lake located in southeastern Winston-Salem. Salem Lake features a seven-mile trail, a lake, and wildlife. The walking trail offers an abundance of activities such as hiking, walking, fishing, biking, dog leashing, running, and more. Salem Lake is often referred to as the "hidden diamond in the city."[77]

- Hanes Mall is a two-story shopping mall that has over 200 stores and five anchor tenants. Hanes Mall serves 25 counties in North Carolina and Virginia. It is the largest shopping mall in the region and covers 1,558,860 square feet and over 200 stores.[78]

- Reynolda House Museum of American Art is an American art museum with collections from the colonial period to present-day art. The museum was built in 1917 by Katherine Smith Reynolds and her spouse R.J. Reynolds. The museum became an art museum in 1967 and first started as a center for education and arts in 1965. Behind the house is a 16-acre lake called "Lake Katherine" and was reverted into wetlands and has a wide variety of wildlife. Many of buildings were changed into shops, boutiques, and restaurants that still operate today. This house still is a main attraction in Winston-Salem.[79]

- Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art is a multimedia contemporary art gallery in Winston-Salem that was founded in 1956 and was accredited by the American Alliance of Museums in 1979. One of 300 museums to receive this accreditation. There is no permanent collection of art exhibits but includes art by artists with regional, national, and international recognition. SECCA has three exhibits with 9,000 square feet obtaining a 300-seat auditorium.[80]

City of Arts and Innovation

Winston-Salem was officially dubbed the "City of Arts and Innovation" in 2014.[81]

Arts

The city created the first arts council in the United States, founded in 1949, and because of the local art schools and attractions. These include the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, The Little Theatre of W-S, Winston-Salem Theatre Alliance, Spirit Gum Theatre Co., the Piedmont Opera Theater, the Winston-Salem Symphony, the Stevens Center for the Performing Arts, the Downtown Arts District, the Milton Rhodes Center for the Arts, the Hanesbrands Theater, Piedmont Craftsmen, and the Sawtooth School for Visual Arts.

The city's Arts District is centered around Sixth and Trade Streets, where there are many galleries, restaurants and workshops; nearby is also the ARTivity on the Green art park, established by Art for Art's Sake.[82]

It is also home to the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art (SECCA), and the Reynolda House Museum of American Art (the restored 1917 mansion built by the founder of the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company[83] and now affiliated with Wake Forest University).

The city plays host to the National Black Theatre Festival, the RiverRun International Film Festival and the Reynolda Film Festival.[84][85]

Winston-Salem is also the home of the Art-o-mat and houses nine of them throughout the city.[86]

The city is also home to Carolina Music Ways, a grassroots arts organization focusing on the area's diverse, interconnected music traditions, including bluegrass, blues, jazz, gospel, old-time stringband, and Moravian music.[87]

Once a year the city is also the home of the Heavy Rebel Weekender music festival, featuring over 70 bands, primarily rockabilly, punk and honky tonk, over three days.

Innovation

The east end of downtown Winston-Salem is anchored by the Innovation Quarter, one of the fastest growing urban-based districts in the United States. Governed by Wake Forest School of Medicine, the Innovation Quarter is home to 90 companies, over 3,600 workers, 1,800 students seeking a college degree, and more than 8,000 workforce trainees. The Innovation Quarter is a place for research, business, biomedical science, digital media, and clinical services. It consists of over 1,900,000 square feet (180,000 m2) feet of office, laboratory, and educational space covering more than 330 acres (130 hectares). There are more than 1,000 residential units within the Innovation Quarter. The goal is to drive even more economic development and create programs for tenants and residents for new ideas. Because of its location in downtown Winston-Salem, the Innovation Quarter serves as an urban, creative, and welcoming place for scientists, innovators, and technology leaders.[88]

In 2019, the Innovation Quarter became one of the first nine steering committee members of the Global Institute on Innovation Districts, making it one of the leading districts of its kind in the world.[89]

Shopping

Winston-Salem is home to Hanes Mall, one of the largest shopping malls in North Carolina, The area surrounding the mall along Stratford Road and Hanes Mall Boulevard has become one of the city's largest shopping districts.[90]

Other notable shopping areas exist in the city, including The Thruway Center (the city's first shopping center), Hanes Point Shopping Center, Hanes Commons, Stratford Commons, Stratford Village, Reynolda Village, Pavilions, Shoppes at Hanestowne Village, Burke Mill Village Shopping Center, Oak Summit Shopping Center, Stone's Throw Plaza, Cloverdale Plaza Shopping Center Silas Creek Crossing, and the Marketplace Mall.

Movies filmed in Winston-Salem

- The Bedroom Window (1987)

- Mr. Destiny (1990)

- Eddie (1996)

- The Lottery, made-for-television adaptation of Shirley Jackson's short story (1996)

- George Washington (2000)

- Brand X, X-Files, episode involving the tobacco industry (2000)

- A Union in Wait (2001, documentary)

- Junebug (2005)[91]

- Lost Stallions: The Journey Home (2008)

- Goodbye Solo (2008)

- Leatherheads (2008)

- Eyeborgs (2009)

- The 5th Quarter (2010)

- Are You Here (2013)

- Goodbye to All That (film) (2014)[92]

- The Longest Ride (2014)[93]

Sports

| Team | Sport | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winston-Salem State University Rams | Basketball | NCAA | C. E. Gaines Center |

| Winston-Salem State University Rams | American Football | NCAA | Bowman Gray Stadium |

| Winston-Salem State University Rams | Softball | NCAA | Washington Park |

| Winston-Salem State University Rams | Tennis | NCAA | WSSU Tennis Center |

| Winston-Salem State University Rams | Track & Field | NCAA | Civitan Park |

| Winston-Salem Dash | Baseball | MiLB | Truist Stadium |

| Carolina Thunderbirds | Ice Hockey | FPHL | Winston-Salem Fairgrounds Annex |

| Winston-Salem Wolves | Basketball | East Coast Basketball League | Childress Center |

| Wake Forest football | American football | NCAA | Truist Field at Wake Forest |

| Wake Forest basketball | Basketball | NCAA | LJVM Coliseum |

The Winston-Salem State University Rams have men's and women's NCAA Division II sports teams that are members of the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA).[94]

The Winston-Salem Dash is a Class High-AA Minor-League baseball team currently affiliated with the Chicago White Sox. After 52 years at historic Ernie Shore Field, the Dash now plays its home games at the new Truist Stadium, which opened in 2010.[95] Previous names for the team include the Winston-Salem Cardinals, Twins, Red Sox, Spirits and, most recently, the Winston-Salem Warthogs.[96] Its players have included Vinegar Bend Mizell, Earl Weaver, Bobby Tiefenauer, Harvey Haddix, Stu Miller, Ray Jablonski, Don Blasingame, Gene Oliver, Rico Petrocelli, Jim Lonborg, George Scott, Sparky Lyle, Bill "Spaceman" Lee, Dwight Evans, Cecil Cooper, Butch Hobson, Wade Boggs, Carlos Lee, Joe Crede, Jon Garland, and Aaron Rowand, all of whom have played extensively at the major league level.

The Carolina Thunderbirds minor league hockey team began play in 2017 at the Winston-Salem Fairgrounds Annex in Winston-Salem.[97]

Wake Forest University is an original member of the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC). Wake Forest's football team plays its games at Truist Field at Wake Forest (formerly BB&T Field, and Groves Stadium), which seats 32,500. Wake Forest's soccer program made four consecutive final four appearances (2006–2009) and were NCAA champions in 2007.[98]

The Lawrence Joel Veterans Memorial Coliseum is home to Wake Forest and some Winston-Salem State basketball games.[99]

NASCAR Whelen All-American Series racing takes place from March until August at Bowman Gray Stadium. The K&N Pro Series East also races here. It is NASCAR's longest-running racing series, dating to the 1940s. In the fall, the stadium is used for Winston-Salem State Rams football games.

Winston-Salem hosts an ATP tennis tournament every year, the Winston-Salem Open. The matches are played at the Wake Forest tennis center.[100]

Education

Public

Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools has most of its schools inside Winston-Salem. WS/FC Schools include 51 elementary schools, 25 middle schools and 13 high schools. The school with the largest student body population is West Forsyth High School with over 2,400 students as of the 2017–2018 school year. The district is the most diverse school system in North Carolina. Winston-Salem/Forsyth County School System is the fourth largest school system in North Carolina with about 59,000 students and over 90 schools operating in the district.[101]

Private

Private and parochial schools also make up a significant portion of Winston-Salem's educational establishment.

- Catholic elementary schools include St. Leo The Great and Our Lady of Mercy. Protestant Christian schools include Winston-Salem Christian School (formerly First Assembly Christian School),[102] Calvary Day School (Baptist),[103] Gospel Light Christian School, Salem Baptist Christian School,[104] Redeemer School (Presbyterian), St. John's Lutheran, Cedar Forest Christian School, Winston-Salem Street School,[105] Salem Montessori School,[106] Berean Baptist Christian School and Woodland Baptist Christian School.[107] Until 2001, Winston-Salem was home to Bishop McGuinness Catholic High School (now in Kernersville, North Carolina), one of only three Catholic high schools in North Carolina.

- Salem Academy, located in Old Salem, has been providing education to young women since 1772.[108]

- Forsyth Country Day School (in nearby Lewisville, North Carolina) and Summit School are secular private schools that serve the area.

Post-secondary institutions

Winston-Salem has a number of colleges and universities, including:

- Wake Forest University, a four-year private research university, founded in 1834 and moved to Winston-Salem in 1956[109]

- Winston-Salem State University, a historically black university founded in 1892[110]

- University of North Carolina School of the Arts (formerly the North Carolina School of the Arts)

- Salem College, the oldest continuously operating educational institution for women in America, founded in 1772[111]

- Forsyth Technical Community College

- Living Arts Institute[112]

- Carolina University (formerly Piedmont International University)[113]

Media

Newspapers

The Winston-Salem Journal is the main daily newspaper in Winston-Salem. Yes! Weekly is a free weekly paper covering news, opinion, arts, entertainment, music, movies and food. Triad City Beat is a free weekly paper in the Triad area that covers Winston-Salem.[114] The Winston-Salem Chronicle is a weekly newspaper that focuses on the African-American community.[115]

Radio stations

These radio stations are located in Winston-Salem, and are listed by call letters, station number, and name. Many more radio stations can be picked up in Winston-Salem that are not located in Winston-Salem.

- WFDD, 88.5 FM, Wake Forest University (NPR Affiliate)

- WBFJ, 89.3 FM, Your Family Station (Contemporary Christian music)

- WSNC, 90.5 FM, Winston-Salem State University (Jazz)

- WXRI, 91.3 FM, Southern Gospel

- WSJS, 600 AM, News-Talk Radio

- WTRU, 830 AM, The Truth (Religious)

- WPIP, 880 AM, Berean Christian School

- WTOB, 980 AM, Classic Hits

- WPOL, 1340 AM, The Light Gospel Music (simulcast on 103.5 FM)

- WWNT, 1380 AM, Top 40 Oldies

- WSMX, 1500 AM, Oldies, Carolina Beach

- WBFJ, 1550 AM, Christian Teaching & Talk Radio

- Wake Radio, Wake Forest University's online, student-run radio station[116]

Television stations

Winston-Salem makes up part of the Greensboro/Winston-Salem/High Point television designated market area. These stations are listed by call letters, channel number, network and city of license.

- WFMY-TV, 2, CBS, Greensboro

- WGHP, 8, Fox, High Point

- WXII-TV, 12, NBC, Winston-Salem

- WGPX, 16, Ion, Burlington

- WCWG, 20, CW, Lexington

- WUNL-TV, 26, PBS/UNC-TV, Winston-Salem

- WLXI-TV, 43, TCT, Greensboro

- WXLV-TV, 45, ABC, Winston-Salem

- WMYV, 48, My, Greensboro

Cable-Only

- Spectrum News 1 North Carolina

Transportation

Public transportation

The Winston-Salem Transit Authority (WSTA) has the responsibility of providing public transportation. It took over from the Safe Bus Company, founded in the 1920s as the largest black-owned transportation company in the United States, in 1972.[117] Operating out of the Clark Campbell Transportation Center at 100 West Fifth Street, WSTA operates 30 daytime bus routes, 24 of which provide night service; 24 routes that operate from morning until midnight on Saturday and 16 Sunday routes. WSTA makes nearly 3 million passenger trips annually. In February 2010 WSTA added 10 diesel-electric buses to its fleet.

The Piedmont Authority for Regional Transportation (PART) operates a daily schedule from the Campbell center connecting Winston-Salem to Boone, Mt. Airy, High Point and Greensboro, where other systems provide in-state routes to points east. PART also offers the Route 5 (Amtrak Connector) which provides daily service to and from the Amtrak Station in High Point with multiple times during the day.[118]

Thoroughfares

US 52 (which runs concurrent with NC 8) is the predominant north–south freeway through Winston-Salem; it passes near the heart of downtown. US 421 is the main east–west freeway through downtown Winston-Salem; this was the original routing of I-40, and was the main east–west route through the city until 1992, when a bypass loop of I-40 was built. US 421 splits in the western part of the city onto its own freeway west (signed north) toward Wilkesboro, North Carolina and Boone, North Carolina. I-74 (which was once US 311) links Winston-Salem to High Point (southeast). Silas Creek Parkway is a partial limited access corridor that traverses from the northwestern section of the city, to the south central section of the city. The corridor bypasses several neighborhoods surrounding downtown and it serves as a popular connector to Wake Forest University, Hanes Mall, The LJVM Coliseum, and Forsyth Tech.[119]

The Winston-Salem Northern Beltway is a proposed freeway that will loop around the city to the north, providing a route for the Future I-74 on the eastern section and the Future Auxiliary Route I-274 on the western section. The NCDOT plans for this project to begin after 2010.

As of November 2018, US 52 south of I-40 is signed Spur Route I-285.

Major arterial thoroughfares in Winston-Salem include Reynolda Road (which also carries NC 67), NC 150 (Peters Creek Parkway), US 158 (Stratford Road), University Parkway, Hanes Mall Boulevard, Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, North Point Boulevard, Country Club Road, Jonestown Road, Patterson Avenue, Fourth Street, Trade Street, Third Street, Liberty Street, and Main Street.

Aviation

Winston-Salem is served by Piedmont Triad International Airport. The airport also serves much of the surrounding Piedmont Triad area, including Greensboro and High Point; the Authority that manages the airport is governed by board members appointed by all three cities as well as both of their counties, Guilford and Forsyth.[120]

A smaller airport, known as Smith Reynolds Airport, is located within the city limits, just northeast of downtown.[121] It is mainly used for general aviation and charter flights. Every year, Smith Reynolds Airport hosts an air show for the general public. The Smith Reynolds Airport is home to the Winston-Salem Civil Air Patrol Composite Squadron, also known as NC-082. The Civil Air Patrol is a non-profit volunteer organization.

Rail

Winston-Salem is one of the larger cities in the South that is not directly served by Amtrak. However, an Amtrak Thruway Motorcoach operates three times daily in each direction between Winston-Salem and the Amtrak station in nearby High Point, 16 miles east. Buses depart from the Winston-Salem Transportation Center, then stop on the Winston-Salem State University campus before traveling to High Point. From the High Point station, riders can board the Crescent, Carolinian or Piedmont lines. These lines run directly to local North Carolina destinations as well as cities across the Southeast, as far west as New Orleans and as far north as New York City.

Notable people

Sister cities

Winston-Salem's sister cities are:[122]

Buchanan, Liberia

Buchanan, Liberia Freeport, Bahamas

Freeport, Bahamas Kumasi, Ghana

Kumasi, Ghana Nassau, Bahamas

Nassau, Bahamas Ungheni, Moldova

Ungheni, Moldova Yangpu (Shanghai), China

Yangpu (Shanghai), China

See also

- List of municipalities in North Carolina

- Arts Council of Winston-Salem Forsyth County

- Interstate 85 in North Carolina

- List of tallest buildings in Winston-Salem

- May 1989 tornado outbreak

- Piedmont Triad

- Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools

References

- the City of Winston-Salem, Mayor of. "City of Winston-Salem, NC :: Meet the Mayor". Winston-Salem, City of. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- "City Manager". City of Winston-Salem. City of Winston-Salem. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-10-25. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Robinson, Ragan (July 13, 2021). "Winston-Salem ranks among nations' top 50 Best places to Live, says US News". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- Shirley, Michael (1997). From Congregation Town to Industrial City. NYU Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8147-8086-2.

- Michael and Martha Hartley. Town of Salem Survey. 1999. Prepared for NC Division of Archives and History.

- Drabble, Jenny (Apr 5, 2015). "Thousands flock to Easter sunrise service in Old Salem". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved Dec 22, 2017.

- "City of Winston-Salem | Town of Winston History". Cityofws.org. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- Hartley. 1999.

- Tursi, Frank (1994). Winston-Salem: A History. John F. Blair, publisher. pp. 110–11, 183. ISBN 978-0-89587-115-2.

- "Washington Park Historic District". Livingplaces.com. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- "Merger of Winston, Salem allowed seeds of industry to sprout". Winston-Salem Journal. 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- Wellman, Manly Wade; Tise, Larry Edward (1976). Winston-Salem in History. Vol. 8. Historic Winston. p. 5.

- "Reynolds Building". Emporis.com. emporis.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- Craver, Richard (2014-05-08). "Panel OKs nomination of RJR building for register". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2014-05-09.

- Craver, Richard (2009-11-23). "Home of RJR on the market". Winston-Salem Journal. Archived from the original on 2009-11-25. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- "Reynolds Building". Allbusiness.com. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- Martin, Jonathan. "Winston-Salem State University". North Carolina History Project. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Williams, Shane. "Wake Forest University". North Carolina History Project. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- "The French Broad hustler. volume (Hendersonville, N.C.) 1896-1912, January 12, 1911, Image 7". The French Broad Hustler. 1911-01-12. ISSN 2375-902X. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- Drabble, Jenny. "Miller's Variety Store to close after 88 years in Winston-Salem". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- Fam (2016-09-11). "Miller's Variety is leaving the building…". North Carolina Collection. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- "The History of Texas Pete". Texas Pete. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Meridian to buy McLean Trucking". The Washington Post. February 5, 1982. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Our Story". Krispy Kreme. Archived from the original on 2018-01-18. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "History - Piedmont International University". Piedmontu.edu. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- "City Council". www.cityofws.com. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Mayor Allen Joines". www.cityofws.com. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "City of Winston-Salem | Home". Cityofws.org. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Winston-Salem city, North Carolina". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- "State Parks in the Triad". ncdr.gov. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- "Distance between High Point, NC & Winston-Salem, NC". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- "Distance between Greensboro, NC & Winston-Salem, NC". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- "Distance between Charlotte, NC & Winston-Salem, NC". www.distance-cities.com. Retrieved August 23, 2021.

- "History of Ardmore". ardmore.ws. 29 May 2020. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- "Buena Vista: A Charming neighborhood in Winston-Salem". Forsythrealty.com. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- www.bizjournals.com https://www.bizjournals.com/triad/print-edition/2014/01/24/winston-salems-most-accident-prone.html. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Fox, Courtney (2022-08-31). "The 20 Best State Fairs Around the U.S. to Visit This Year". Wide Open Country. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- Young, Wesley. "Move to turn Budget Inn on Peters Creek Parkway into mixed-use development with affordable housing endorsed by city panel". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- "City approves Budget Inn rezoning, delays Ardmore townhouses". WS Chronicle. 2018-05-10. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- "Winston-Salem, North Carolina Köppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Average Weather for Winston-Salem, NC – Temperature and Precipitation". Weather.com. July 27, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- "Station: Winston Salem RYNLDS AP, NC". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Winston-Salem city, North Carolina". www.census.gov. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Selected Historical Decennial Census Population and Housing Counts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved 2021-12-20.

- "QuickFacts Winston-Salem city, North Carolina". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Households and Families: 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". American Fact Finder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Age and Sex: 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Hispanic or Latino Origin by Race: 2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "American FactFinder - Results". 7 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2018.[dead link]

- "Winston-Salem, North Carolina Religion". Bestplaces.net. 2015-07-07. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Dec. 3, 2009: Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center to Hold Annual Star Lighting Service". Wfubmc.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Lowes Foods – Company History". Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- "Group Sales Archived 2011-12-08 at the Wayback Machine." K&W Cafeterias. Retrieved on January 31, 2012. "K&W Corporate Office P.O. Box 25048 Winston-Salem, NC 27114-5048"

- Daniel, Fran (January 15, 2012). "K&W turns 75". Winston-Salem Journal. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2012. – "Headquarters: 1391 Plaza West Road, off Healy Drive in Winston-Salem"

- "Garner Foods considers moving corporate headquarters downtown". Winston-Salem Journal. March 6, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014. – "based at 4045 Indiana Ave"

- "Winston-Salem's hottest startup aims to disrupt the world of blockchain". Innovation Quarter. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- WRAL (2009-10-07). "Dell to close N.C. plant, eliminate 905 jobs". WRAL.com. Retrieved 2022-11-06.

- Daniel, Fran (January 16, 2015). "Herbalife officially opens it's Winston-Salem Plant". www.journalnow.com. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "Lofty plans take shape as Wake Forest Innovation Quarter eyes $1.7 billion public-private investment by 2030". Winston-Salem Journal. January 14, 2017.

- "Major Employers". Wsbusinessinc.com. 2013-10-02. Archived from the original on 2017-03-15. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Major Industries". Wsbusinessinc.com. 2013-10-02. Archived from the original on 2017-03-15. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Home". Old Salem. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Cobblestone Farmers Market | Visit Winston Salem". visitwinstonsalem.com. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- "About Us". Cobblestone Farmers Market. Retrieved 2019-03-26.

- "History – Reynolda Gardens". Reynolda Gardens of Wake Forest University. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "The Science Center and Environmental Park of Winston-Salem NC. Forsyth County's Science Museum". SciWorks. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Kaleideum's History". Kaleideum. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "New Winston Museum - Winston-Salem and Forsyth County's Community Museum". New Winston Museum. Retrieved 2016-01-13.

- "Tanglewood Park – Forsyth County". forsyth.cc. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "The Winston-Salem Fairgrounds – About us". www.wsfaurgrounds.com. December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "About Salem lake". www.cityofws.org. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Hanes Mall Official website". Hanes Mall. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "About Reynolda House Museum of American Art". www.reynoldahouse.org. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "About SECCA". www.secca.org. December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Journal, Wesley Young/Winston-Salem. "It's official: 'City of Arts and Innovation'". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- "ARTivity History -". Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- "Reynolda House Museum of American Art". Reynoldahouse.org. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "National Black Theatre Festival – Our History". ncblackrep.org. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "Riverrun International Film Festival – Home". Riverrunfilm.com. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- Roberts, Karen (November 8, 2016). "Out of cigarettes? Art-O-Mat dispenses diminutive paintings, sculptures". USA Today. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- "About Carolina Music Ways". www.carolinamusicways.org. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Innovation Quarter: A History". www.innovationquarter.com. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Innovation Quarter selected to join newly formed Global Institute on Innovation Districts". Innovation Quarter. Retrieved 2020-02-15.

- Garber, Paul (December 1, 2017). "Hanes Mall opened in 1975, How many stores do you remember?". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- Clodfelter, Tim (September 9, 2020). "Junebug filmed here, celebrates 15th anniversary with a drive-in screening". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "Tim's top five movies filmed in Winston-Salem". www.journalnow.com. Retrieved January 1, 2015.

- "The longest ride; movie filmed in Winston-Salem, opens to 13.5 million". www.myfox8.com. Retrieved April 12, 2015.

- "Winston-Salem State University Athletic department". wssurams.com. 12 May 2015. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "Official website of Winston-Salem Dash". milb.com. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- [dead link]

- "History of WS Hockey". Carolina Thunderbirds. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Wake Forest Athletics – Wake Forest University". Wake Forest Demon Deacons. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- "About Lawrence Joel". LJVM.com. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- "Winston-Salem Open – Overview". atptour.com. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "About WS/FCS". www.wsfcs.com. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Winston-Salem Christian School – Who are we?". wschristian.com. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "Calvary Day School homepage". calvaryday.school. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "Salem Baptist Christian School | Private K4-12 School | NC". SalemVikings. Retrieved 2021-12-22.

- "Winston-Salem Street School – About us". wsstreetschool.org. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "Why Salem Montessori School?". salem-montessori.org. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "Welcome to Woodland Baptist Christian School". wbcseagles.com. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "History of Salem Academy". www.salemacademy.com. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "About Wake Forest". www.about.wfu.edu. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- "Our History - Winston-Salem State University". www.wssu.edu. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "About Salem". www.salem.edu. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Living Arts College - Medical Arts Programs". 27 May 2012. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012.

- "History of Carolina University". carolinau.edu. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- "About". Triad City Beat. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- "About Us". The Winston-Salem Chronicle. Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- "Wake Radio | Wake Forest University College Radio". Radio.wfu.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2017-04-02.

- "Winston Salem Transit Authority". www.wstransit.com. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "About PART". www.partnc.org. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Northwest Almanac: Early days of Silas Creek Parkway". Winston-Salem Journal. October 30, 2017. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- "About PTI – Piedmont Triad International Airport". flyfrompti.com. 15 January 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- "History of Smith Reynolds airport". www.smithreyonlds.org. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- "Our Sister Cities". winstonsalemsistercities.org. Winston-Salem Sister Cities. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

Bibliography

External links

- Official website

Winston-Salem travel guide from Wikivoyage

Winston-Salem travel guide from Wikivoyage- Visit Winston-Salem

- Winston-Salem, North Carolina at Curlie

На других языках

[de] Winston-Salem

Winston-Salem ist eine Großstadt im Forsyth County im US-Bundesstaat North Carolina. Die Stadt ist die fünftgrößte des Bundesstaates und liegt in der Piedmont Triad Region.- [en] Winston-Salem, North Carolina

[ru] Уинстон-Сейлем

Уи́нстон-Се́йлем (англ. Winston-Salem) — город на востоке США, штат Северная Каролина. 234 349 жителей (2012). Крупнейший в США центр текстильной и табачной промышленности. Развито машиностроение, мебельная, швейная и др. промышленность. Университет. В городе ежегодно проходит открытый чемпионат Уинстон-Сейлема по теннису, предваряющий Открытый чемпионат США по теннису.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии