world.wikisort.org - USA

Minneapolis (/ˌmɪniˈæpəlɪs/ (![]() listen)) is the largest city in Minnesota and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins in timber and as the flour milling capital of the world. It occupies both banks of the Mississippi River and adjoins Saint Paul, the state capital of Minnesota.

listen)) is the largest city in Minnesota and the county seat of Hennepin County. The city is abundant in water, with thirteen lakes, wetlands, the Mississippi River, creeks and waterfalls. Minneapolis has its origins in timber and as the flour milling capital of the world. It occupies both banks of the Mississippi River and adjoins Saint Paul, the state capital of Minnesota.

Minneapolis, Minnesota | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Minneapolis | |

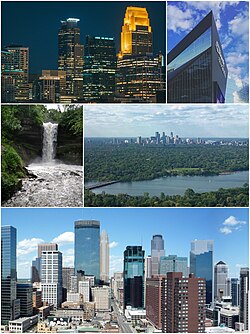

Clockwise from top left: Downtown Minneapolis at night; U.S. Bank Stadium; skyline from Lake Nokomis; Minneapolis skyline; and Minnehaha Falls | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Etymology: Dakota word mni ('water') with Greek polis ('city') | |

| Nickname(s): "City of Lakes", "Mill City", "Twin Cities" (with Saint Paul), "Mini Apple" | |

| Motto: En Avant (French: 'Forward') | |

Interactive map of Minneapolis | |

| Coordinates: 44°58′55″N 93°16′09″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Minnesota |

| County | Hennepin |

| Incorporated | 1867 |

| Founded by | John H. Stevens and Franklin Steele |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council (strong mayor)[1] |

| • Body | Minneapolis City Council |

| • Mayor | Jacob Frey (DFL) |

| Area | |

| • City | 57.51 sq mi (148.94 km2) |

| • Land | 54.00 sq mi (139.86 km2) |

| • Water | 3.51 sq mi (9.08 km2) |

| Elevation | 830 ft (264 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 429,954 |

| • Estimate (2021)[3] | 425,336 |

| • Rank | 46th in the United States 1st in Minnesota |

| • Density | 7,962.11/sq mi (3,074.21/km2) |

| • Metro | 3,690,512 (16th) |

| Demonym | Minneapolitan |

| Time zone | UTC–6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 55401-55419, 55423, 55429-55430, 55450, 55454-55455, 55484-55488 |

| Area code | 612 |

| FIPS code | 27-43000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0655030[5] |

| Major airport | Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport |

| Interstates | |

| U.S. Routes | |

| State Highways | |

| Public transportation | Metro Transit |

| Website | Minneapolis.org MinneapolisMN.gov |

Prior to European settlement, the site of Minneapolis was inhabited by Dakota people. The settlement was founded along Saint Anthony Falls on a section of land north of Fort Snelling; its growth is attributed to its proximity to the fort and the falls providing power for industrial activity. As of 2021[update], the city has an estimated 425,336 inhabitants.[3] It is the most populous city in the state and the 46th-most-populous city in the United States. Minneapolis, Saint Paul and the surrounding area are collectively known as the Twin Cities.

Minneapolis has one of the most extensive public park systems in the US; many of these parks are connected by the Grand Rounds National Scenic Byway. Biking and walking trails, some of which follow abandoned railroad lines, run through many parts of the city; such as the Mill District in the Saint Anthony Falls Historic District, around the banks of Lake of the Isles, Bde Maka Ska, and Lake Harriet, and by Minnehaha Falls. Minneapolis has cold, snowy winters and hot, humid summers. Minneapolis is the birthplace of General Mills, Pillsbury Company, and the Target Corporation. The city's cultural offerings include the Guthrie Theater, the First Avenue nightclub, and four professional sports teams.

Most of the University of Minnesota's main campus, and several other post-secondary educational institutions are in Minneapolis. Part of the city is served by a light rail system.

Minneapolis has a mayor-council government system. The Minnesota Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party (DFL) has held a majority of council seats there for 50 years and Jacob Frey (DFL) has been mayor since 2018. In May 2020, Derek Chauvin, a White officer of the Minneapolis Police Department, murdered George Floyd, a Black man, and the resulting global protests put Minneapolis and racism at the center of national and international attention.

History

Dakota natives, city founded

Prior to European settlement, the Dakota Sioux were the sole occupants of the site of modern-day Minneapolis. In Dakota language, the city's name is Bde Óta Othúŋwe ('Many Lakes Town').[lower-alpha 1] The French explored the region in 1680. Gradually, more European-American settlers arrived, competing with the Dakota for game and other natural resources. Following the Revolutionary War, the 1783 Treaty of Paris gave British-claimed territory east of the Mississippi River to the United States.[8] In 1803, the U.S. acquired land to the west of the Mississippi from France in the Louisiana Purchase. In 1819, US Army built Fort Snelling at the southern edge of present-day Minneapolis[9] to direct Native American trade away from British-Canadian traders, and to deter warring between the Dakota and Ojibwe in northern Minnesota.[10] The fort attracted traders, settlers and merchants, spurring growth in the surrounding region. At the fort, agents of the St. Peters Indian Agency enforced the US policy of assimilating Native Americans into European-American society, encouraging them to give up subsistence hunting and to cultivate the land.[11] Missionaries encouraged Native Americans to convert from their own religion to Christianity.[11]

The U.S. government pressed the Dakota to sell their land, which they ceded in a series of treaties that were negotiated by corrupt officials.[12] In the decades following the signings of these treaties, their terms were rarely honored.[13] During the American Civil War, officials plundered annuities promised to Native Americans, leading to famine among the Dakota.[14] In 1862, a faction of the Dakota who were facing starvation[15] declared war and killed settlers. The Dakota were interned and exiled from Minnesota.[16] While the Dakota were being expelled, Franklin Steele laid claim to the east bank of Saint Anthony Falls,[10] and John H. Stevens built a home on the west bank.[17] Residents had divergent ideas on names for their community. In 1852, Charles Hoag proposed combining the Dakota word for 'water' (mni[lower-alpha 2]) with the Greek word for 'city' (polis), yielding Minneapolis. In 1851 after a meeting of the Minnesota Territorial Legislature, leaders of St. Anthony lost their bid to move the capital from Saint Paul.[22] In a close vote, St. Paul and Stillwater agreed to divide federal funding[22] between them: St. Paul would be the capital, while Stillwater would build the prison. The St. Anthony contingent eventually won the state university.[22] In 1856, the territorial legislature authorized Minneapolis as a town on the Mississippi's west bank.[23] Minneapolis was incorporated as a city in 1867 and in 1872, it merged with the city of St. Anthony on the river's east bank.[24]

Waterpower; lumber and flour milling

Minneapolis developed around Saint Anthony Falls, the highest waterfall on the Mississippi River, which was used as a source of energy. A lumber industry was built around forests in northern Minnesota, and 17 sawmills operated from energy provided by the waterfall. By 1871, the river's west bank had 23 businesses, including flour mills, woolen mills, iron works, a railroad machine shop, and mills for cotton, paper, sashes and wood-planing.[25] Due to the occupational hazards of milling, by the 1890s, six companies manufactured artificial limbs.[26] Grain grown in the Great Plains was shipped by rail to the city's 34 flour mills. A 1989 Minnesota Archaeological Society analysis of the Minneapolis riverfront describes the use of water power in Minneapolis between 1880 and 1930 as "the greatest direct-drive waterpower center the world has ever seen".[27] Minneapolis led the world[clarification needed] in flour milling for 50 years.[27]

Cadwallader C. Washburn, a founder of modern milling and of what became General Mills, converted his business from gristmills to "gradual reduction" by steel-and-porcelain roller mills that were capable of quickly producing premium-quality, pure, white flour.[28][29] William Dixon Gray developed some ideas[30] and William de la Barre acquired others through industrial espionage in Hungary.[29] Charles Alfred Pillsbury and the C.A. Pillsbury Company across the river hired Washburn employees and immediately began using the new methods.[29]

An 1867 court case allowed digging the Eastman tunnel under the river at Nicollet Island.[31] In 1869, a leak soon sucked the 6 ft (1.8 m) tailrace into a 90 ft (27 m)-wide chasm.[31] Community-led repairs failed and in 1870, several buildings and mills fell into the river.[31] For years, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers struggled to close the gap with timber until their concrete dike held in 1876.[31]

The hard, red, spring wheat grown in Minnesota became valuable ($0.50 profit per barrel in 1871 increased to $4.50 in 1874),[28] and Minnesota "patent" flour was recognized as the best in the world.[29] Later consumers discovered value in the bran that " ... Minneapolis flour millers routinely dumped" into the Mississippi.[32] A single mill at Washburn-Crosby could make enough flour for 12 million loaves of bread each day[33] and by 1900, 14 percent of America's grain was milled in Minneapolis.[28][29] By 1895, through the efforts of silent partner William Hood Dunwoody, Washburn-Crosby exported four million barrels of flour a year to the United Kingdom.[34] When exports reached their peak in 1900, about one third of all flour milled in Minneapolis was shipped overseas.[34]

Social tensions

In 1886, when Martha Ripley founded Maternity Hospital for both married and unmarried mothers, Minneapolis made changes to rectify discrimination against unmarried women.[35] Known initially as a kindly physician, mayor Doc Ames made his brother police chief, ran the city into corruption, and tried to leave town in 1902.[36] Lincoln Steffens published Ames's story in "The Shame of Minneapolis" in 1903.[37] Minneapolis has a long history of structural racism[38] and has large racial disparities in housing, income, health care, and education.[39][40] Some historians and commentators have said White Minneapolitans used discrimination based on race against the city's non-White residents. As White settlers displaced the indigenous population during the 19th century, they claimed the city's land,[41] and Kirsten Delegard of Mapping Prejudice explains that today's disparities evolved from control of the land.[40] In 1910, Minneapolis "was not a particularly segregated place".[40] Discrimination increased when flour milling moved to the east coast and the economy declined.[42]

During the early 20th century, bigotry presented in several ways. In 1910, a Minneapolis developer wrote restrictive covenants based on race and ethnicity into his deeds. Other developers copied the practice, preventing Asian and African Americans from owning or leasing certain properties. Though such language was prohibited by state law in 1953 and by the federal Fair Housing Act of 1968, restrictive covenants against minorities remained in many Minneapolis deeds as recently as 2021, when the city gave residents a means to remove them.[43][44] The Ku Klux Klan entered family life but was only effectively a force in the city from 1921 until 1923.[45] The gangster Kid Cann engaged in bribery and intimidation between the 1920s and the 1940s.[46] After Minnesota passed a eugenics law in 1925, the proprietors of Eitel Hospital sterilized about 1,000 people at Faribault State Hospital.[47] From the end of World War I in 1918 until 1950, antisemitism was commonplace in Minneapolis—Carey McWilliams called the city the anti-Semitic capital of the United States.[48] A hate group called the Silver Legion of America held meetings in the city from 1936 to 1938.[49] In 1948, Mount Sinai Hospital opened as the city's first hospital to employ members of minority races and religions.[50][49]

During the financial downturn of the Great Depression, the violent Teamsters Strike of 1934 led to laws acknowledging workers' rights.[51] Mayor Hubert Humphrey helped the city establish fair employment practices and by 1946, a human-relations council that interceded on behalf of minorities was established.[52] In 1966 and 1967, years of significant turmoil across the US, suppressed anger among the Black population was released in two disturbances on Plymouth Avenue.[53] A coalition reached a peaceful outcome but failed to solve Black poverty and unemployment; Charles Stenvig, a law-and-order candidate, became mayor.[54] Minneapolis contended with White supremacy, participated in desegregation and engaged with the civil rights movement; in 1968, the American Indian Movement was founded in Minneapolis.[55] Between 1958 and 1963, as part of urban renewal in America,[56] Minneapolis demolished roughly 40 percent of downtown, including the Gateway District and its significant architecture, such as the Metropolitan Building. Efforts to save the building failed but encouraged interest in historic preservation.[57]

On May 25, 2020, a citizen recorded the murder of George Floyd, an African-American man who suffocated when Derek Chauvin, a White Minneapolis police officer, knelt on Floyd's neck and back for more than nine minutes. The incident sparked national unrest, riots and mass protests.[58] Local protests and riots resulted in extraordinary levels of property damage in Minneapolis;[59] the destruction including a police station that demonstrators overran and set on fire.[60] The Twin Cities experienced prolonged unrest over racial injustice from 2020 to 2022.[61]

Geography

![View of downtown Minneapolis across Bde Maka Ska (previously named Lake Calhoun)[62]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0a/Lake_Calhoun_MN.jpg/220px-Lake_Calhoun_MN.jpg)

The history and economic growth of Minneapolis are linked to water, the city's defining physical characteristic. Long periods of glaciation and interglacial melt carved several riverbeds through what is now Minneapolis.[63] During the last glacial period, around 10,000 years ago, ice buried in these ancient river channels melted, resulting in basins that filled with water to become the lakes of Minneapolis.[63] Meltwater from Lake Agassiz fed the glacial River Warren, which created a large waterfall that eroded upriver past the confluence of the Mississippi River, where it left a 75-foot (23 m) drop in the Mississippi. This site is located in what is now downtown Saint Paul.[64] The new waterfall, later called Saint Anthony Falls, in turn eroded up the Mississippi about eight miles (13 km) to its present location, carving the Mississippi River gorge as it moved upstream. Minnehaha Falls also developed during this period via similar processes.[64][63]

Minneapolis is sited above an artesian aquifer[65] and on flat terrain. Minneapolis has a total area of 59 square miles (152.8 km2), six percent of which is covered by water.[66] Water supply is managed by four watershed districts that correspond with the Mississippi and the city's three creeks.[67] The city has thirteen lakes, three large ponds, and five unnamed wetlands.[67]

A 1959 report by the U.S. Soil Conservation Service listed Minneapolis's elevation above mean sea level as 830 feet (250 m).[68] The city's lowest elevation of 687 feet (209 m) above sea level is near the confluence of Minnehaha Creek with the Mississippi River.[69][70] Sources disagree on the exact location and elevation of the city's highest point, which is cited as being between 965 and 985 feet (294 and 300 m) above sea level.[lower-alpha 3]

Neighborhoods

Minneapolis is divided into eleven communities, each containing several neighborhoods, of which there are 83. In some cases, two or more neighborhoods act together under one organization. Some areas are known by nicknames of business associations.[73]

In 2018, Minneapolis City Council voted to approve the Minneapolis 2040 Comprehensive Plan, which resulted in a city-wide end to single-family zoning. Minneapolis was the first major city in the United States to make this change.[74] At the time, 70 percent of residential land was zoned for detached, single-family homes, however many of those areas had "nonconforming" buildings with more housing units. City leaders sought to increase the supply of housing so more neighborhoods would be affordable and to decrease the effects single-family zoning had caused on racial disparities and segregation.[75] The Brookings Institution called it "a relatively rare example of success for the YIMBY agenda".[76] A Hennepin County District Court judge blocked the city from enforcing the plan because it lacked an overall environmental review. Arguing it will evaluate projects on an individual basis, as of July 2022, the city is allowed to use the plan while an appeal is pending.[77]

Cityscape

Climate

Minneapolis experiences a hot-summer humid continental climate (Dfa in the Köppen climate classification),[78] that is typical of southern parts of the Upper Midwest, and is situated in USDA plant hardiness zone 4b; small enclaves of Minneapolis are classified as zone 5a.[79][80][81] Minneapolis has cold, snowy winters and hot, humid summers, as is typical in a continental climate. The difference between average temperatures in the coldest winter month and the warmest summer month is 58.1 °F (32.3 °C).

According to the NOAA, the annual average for sunshine duration is 58%.[82] Minneapolis experiences a full range of precipitation and related weather events, including snow, sleet, ice, rain, thunderstorms, and fog. The highest recorded temperature is 108 °F (42 °C) in July 1936 while the lowest is −41 °F (−41 °C) in January 1888. The snowiest winter on record was 1983–84, when 98.6 inches (250 cm) of snow fell:[83] the least-snowiest winter was 1890–91, when 11.1 inches (28 cm) fell.[84]

| Climate data for Minneapolis/St. Paul International Airport (1991–2020 normals,[lower-alpha 4] extremes 1871–present)[lower-alpha 5] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

64 (18) |

83 (28) |

95 (35) |

106 (41) |

104 (40) |

108 (42) |

103 (39) |

104 (40) |

90 (32) |

77 (25) |

68 (20) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 42.5 (5.8) |

46.7 (8.2) |

64.7 (18.2) |

79.7 (26.5) |

88.7 (31.5) |

93.3 (34.1) |

94.4 (34.7) |

91.7 (33.2) |

88.3 (31.3) |

80.1 (26.7) |

62.1 (16.7) |

47.1 (8.4) |

96.4 (35.8) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 23.6 (−4.7) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

41.7 (5.4) |

56.6 (13.7) |

69.2 (20.7) |

79.0 (26.1) |

83.4 (28.6) |

80.7 (27.1) |

72.9 (22.7) |

58.1 (14.5) |

41.9 (5.5) |

28.8 (−1.8) |

55.4 (13.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 16.2 (−8.8) |

20.6 (−6.3) |

33.3 (0.7) |

47.1 (8.4) |

59.5 (15.3) |

69.7 (20.9) |

74.3 (23.5) |

71.8 (22.1) |

63.5 (17.5) |

49.5 (9.7) |

34.8 (1.6) |

22.0 (−5.6) |

46.9 (8.3) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 8.8 (−12.9) |

12.7 (−10.7) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

37.5 (3.1) |

49.9 (9.9) |

60.4 (15.8) |

65.3 (18.5) |

62.8 (17.1) |

54.2 (12.3) |

40.9 (4.9) |

27.7 (−2.4) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

38.4 (3.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −14.7 (−25.9) |

−8 (−22) |

2.7 (−16.3) |

21.9 (−5.6) |

35.7 (2.1) |

47.3 (8.5) |

54.5 (12.5) |

52.3 (11.3) |

38.2 (3.4) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

9.2 (−12.7) |

−7.1 (−21.7) |

−16.9 (−27.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −41 (−41) |

−33 (−36) |

−32 (−36) |

2 (−17) |

18 (−8) |

34 (1) |

43 (6) |

39 (4) |

26 (−3) |

10 (−12) |

−25 (−32) |

−39 (−39) |

−41 (−41) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.89 (23) |

0.87 (22) |

1.68 (43) |

2.91 (74) |

3.91 (99) |

4.58 (116) |

4.06 (103) |

4.34 (110) |

3.02 (77) |

2.58 (66) |

1.61 (41) |

1.17 (30) |

31.62 (803) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 11.0 (28) |

9.5 (24) |

8.2 (21) |

3.5 (8.9) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.8 (2.0) |

6.8 (17) |

11.4 (29) |

51.2 (130) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.6 | 7.8 | 9.0 | 11.2 | 12.4 | 11.8 | 10.4 | 9.8 | 9.3 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 9.7 | 118.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 9.3 | 7.3 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 8.8 | 38.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.9 | 69.5 | 67.4 | 60.3 | 60.4 | 63.8 | 64.8 | 67.9 | 70.7 | 68.3 | 72.6 | 74.1 | 67.5 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 4.1 (−15.5) |

9.5 (−12.5) |

20.7 (−6.3) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

43.5 (6.4) |

54.7 (12.6) |

60.1 (15.6) |

58.3 (14.6) |

49.8 (9.9) |

37.9 (3.3) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

11.1 (−11.6) |

33.9 (1.0) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 156.7 | 178.3 | 217.5 | 242.1 | 295.2 | 321.9 | 350.5 | 307.2 | 233.2 | 181.0 | 112.8 | 114.3 | 2,710.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 55 | 61 | 59 | 60 | 64 | 69 | 74 | 71 | 62 | 53 | 39 | 42 | 59 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[86][87][88] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[89] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Racial composition | 2020[90] | 2010[90] | 1990[91] | 1970[91] | 1950[91] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 58.0% | 60.3% | 77.5% | 92.8% | n/a |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 18.9% | 18.3% | 13.0% | 4.4% | 1.3% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 10.4% | 10.5% | 2.1% | 0.9% | n/a |

| Asian (non-Hispanic) | 5.8% | 5.6% | 4.3% | 0.4% | 0.2% |

| Other race (non-Hispanic) | 0.5% | 0.3% | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Two or more races (non-Hispanic) | 5.2% | 3.4% | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 5,809 | — | |

| 1870 | 13,066 | 124.9% | |

| 1880 | 46,887 | 258.8% | |

| 1890 | 164,738 | 251.4% | |

| 1900 | 202,718 | 23.1% | |

| 1910 | 301,408 | 48.7% | |

| 1920 | 380,582 | 26.3% | |

| 1930 | 464,356 | 22.0% | |

| 1940 | 492,370 | 6.0% | |

| 1950 | 521,718 | 6.0% | |

| 1960 | 482,872 | −7.4% | |

| 1970 | 434,400 | −10.0% | |

| 1980 | 370,951 | −14.6% | |

| 1990 | 368,383 | −0.7% | |

| 2000 | 382,618 | 3.9% | |

| 2010 | 382,578 | 0.0% | |

| 2020 | 429,954 | 12.4% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 425,336 | [3] | −1.1% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[92] 2020 Census | |||

Dakota tribes, mostly the Mdewakanton, permanently occupied the present-day site of Minneapolis near their sacred site, St. Anthony Falls.[24] During the 1850s and 1860s, European and Euro-American settlers from New England, New York, Bohemia[93] and Canada, and, during the mid-1860s, immigrants from Finland, Sweden, Norway and Denmark moved to the Minneapolis area, as did migrant workers from Mexico and Latin America.[94] Other migrants came from Germany, Poland, Italy, and Greece. Central European migrants settled in the Northeast neighborhood, which is still known for its Czech[95] and Polish cultural heritage. Jews from Central and Eastern Europe, and Russia began arriving in the 1880s, and settled primarily on the north side before moving to western suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s.[96]

For a short period of the 1940s, Japanese and Japanese Americans resided in Minneapolis due to US-government relocations, as did Native Americans during the 1950s. In 2013, Asians were the state's fastest-growing population. Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, Hmong, Lao, Cambodians and Vietnamese arrived in the 1970s and 1980s, and people from Tibet, Burma and Thailand came in the 1990s and 2000s.[97] The population of people from India doubled by 2010.[98] After the Rust Belt economy declined during the early 1980s, Minnesota's Black population, a large fraction of whom arrived from cities such as Chicago and Gary, Indiana, nearly tripled in less than twenty years.[99] Black migrants were drawn to Minneapolis and the Greater Twin Cities by its abundance of jobs, good schools, and relatively safe neighborhoods. Beginning in the 1990s, a sizable Latin American population arrived, along with immigrants from the Horn of Africa, especially Somalia;[100] however, immigration of 1,400 Somalis in 2016 slowed to 48 in 2018 under President Trump.[101] As of 2019, more than 20,000 Somalis live in Minneapolis.[102] In 2015, the Brookings Institution characterized Minneapolis as a re-emerging immigrant gateway where about 10 percent of residents were born outside the US.[103] As of 2019, African Americans make up about one fifth of the city's population.

The population of Minneapolis grew until 1950, when the census peaked at 521,718—the only time it has exceeded a half million. The population then declined for decades; after World War II, people moved to the suburbs, and generally out of the Midwest.[104]

In 2015, Gallup reported the Twin Cities had an estimated LGBT+ adult population of 3.6%, roughly the same as the national average, and had the 38th-highest number of LGBT+ residents of the 50 largest metropolitan areas in the US.[105] Human Rights Campaign gave Minneapolis its highest-possible score in 2019.[106]

A Black family in Minneapolis earns less than half as much per year as a White family. Black people own their homes at one-third the rate of White families. Specifically, the median income for a Black family was $36,000 in 2018, about $47,000 less than for a white family. Black Minneapolitans thus earn about 44 percent per year compared to White Minneapolitans, one of the country's largest income gaps.[107] A 2020 study found little change in economic racial inequality, with Minnesota ranking above only the neighboring state Wisconsin, and equal to the states of Iowa, Louisiana, and New Mexico.[108]

Religion

The indigenous Dakota people, the original inhabitants of the Minneapolis area, believed in the Great Spirit and were surprised not all European settlers were religious.[110] More than 50 denominations and religions are present in Minneapolis; a majority of the city's population are Christian. Settlers who arrived from New England were for the most part Protestants, Quakers, and Universalists.[110] The oldest continuously used church, Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church, was built in 1856 by Universalists and soon afterward was acquired by a French Catholic congregation.[111] The first Jewish congregation was formed in 1878 as Shaarai Tov, and built Temple Israel in 1928.[96] St. Mary's Orthodox Cathedral was founded in 1887; it opened a missionary school and created the first Russian Orthodox seminary in the US.[112] Edwin Hawley Hewitt designed St. Mark's Episcopal Cathedral and Hennepin Avenue United Methodist Church, both of which are located south of downtown.[113] The Basilica of Saint Mary, the first basilica in the US and co-cathedral of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Saint Paul and Minneapolis, was named by Pope Pius XI in 1926.[110]

![Christ Church Lutheran is a National Historic Landmark.[114]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/22/Christ_Church_Lutheran_Highsmith.jpg/220px-Christ_Church_Lutheran_Highsmith.jpg)

By 1959, Temple of Islam was located in north Minneapolis, and the Islamic Center of Minnesota was established in 1965.[115] The city's first mosque was built in 1967.[116] Somalis who live in Minneapolis are primarily Sunni Muslim.[117] In 1971, a reported 150 persons attended classes at a Hindu temple near the university.[115] In 1972, a relief agency resettled the first Shi'a Muslim family from Uganda in the Twin Cities.[118] The city has about 20 Buddhist centers and meditation centers.[119] Minneapolis has a body of Ordo Templi Orientis.[120]

The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association was headquartered in Minneapolis from the late 1940s until the early 2000s.[121] Jim Bakker and Tammy Faye met while attending Pentecostal North Central University, and began a television ministry that by the 1980s reached 13.5 million households.[122] As of 2012, Mount Olivet Lutheran Church in southwest Minneapolis was the nation's second-largest Lutheran congregation, with about 6,000 attendees.[123] Christ Church Lutheran in the Longfellow neighborhood, the final work in the career of Eliel Saarinen, has an education building designed by his son Eero Saarinen.[114]

Economy

| Top publicly traded Minneapolis companies for 2021 with city and US ranks Source: Fortune 500[124] | |||||||

| Mpls | Corporation | US | Revenue (in millions) | ||||

| 1 | Target Corporation | 30 | $93,561 | ||||

| 2 | U.S. Bancorp | 113 | $25,241 | ||||

| 3 | Ameriprise Financial | 253 | $11,958 | ||||

| 4 | Xcel Energy | 272 | $11,526 | ||||

| 5 | Thrivent | 369 | $8,152.7 | ||||

| Top Minneapolis employers in 2020 Source: Twin Cities Business[125] | |||||||

| Rank | Company/Organization | ||||||

| 1 | Target Corporation | ||||||

| 2 | Hennepin Healthcare | ||||||

| 3 | Wells Fargo | ||||||

| 4 | Hennepin County | ||||||

| 5 | U.S. Bancorp | ||||||

| 6 | Ameriprise Financial | ||||||

| 7 | Xcel Energy | ||||||

| 8 | City of Minneapolis | ||||||

| 9 | RBC Wealth Management | ||||||

| 10 | Strategic Education | ||||||

As of 2020, the Minneapolis–St. Paul area is the second-largest economic center in the American Midwest behind Chicago.[126] Early the city's history, millers were required to pay for wheat with cash during the growing season, and then to store the wheat until it was needed for flour. This required large amounts of capital, which stimulated the local banking industry and made Minneapolis a major financial center.[127] As of mid-2022, Minneapolis area employment is primarily in trade, transportation, utilities, education, health services, professional and business services. Smaller numbers are employed in manufacturing, leisure and hospitality; mining, logging, and construction.[128]

The Twin Cities metropolitan area has the seventh-highest concentration of major corporate headquarters in the US as of 2021,[129] and in 2020, four Fortune 500 corporations were headquartered within the city limits of Minneapolis.[130] American companies with US offices in Minneapolis include Accenture, Bellisio Foods,[131] Canadian Pacific, Coloplast,[132] RBC[133] and Voya Financial.[134] The National Institute for Pharmaceutical Technology & Education has Minneapolis headquarters.

As of 2020, the Minneapolis metropolitan area contributes $273 billion or 74% to the gross state product of Minnesota.[135] Measured by gross metropolitan product per resident ($62,054), as of 2015, Minneapolis is the fifteenth richest city in the US.[136] In 2011, the area's $199.6 billion gross metropolitan product and its per capita personal income ranked 13th in the US.[137]

The Minneapolis Grain Exchange, which was founded in 1881, is located near the riverfront and is the only exchange for hard, red, spring wheat futures and options.[138] The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis serves Minnesota, Montana, North and South Dakota, and parts of Wisconsin and Michigan; it has the smallest population of the 12 regional banks in the Federal Reserve System.[139] Along with supporting consumers and the community, the bank executes monetary policy, regulates banks in its territory, and provides cash and oversees electronic deposits.[140]

Arts and culture

Visual arts

![Minneapolis Institute of Art has a collection of 90,000 objects spanning 20,000 years.[141]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d9/Minneapolis_Institute_of_Arts.jpg/220px-Minneapolis_Institute_of_Arts.jpg)

Walker Art Center is located at the summit of Lowry Hill near downtown. The center's size doubled in 2005 with an addition by Herzog & de Meuron, and expanded with a 15-acre (6.1 ha) park that was designed by Michel Desvigne and is located across the street from the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden.[142]

Minneapolis Institute of Art, which is known as Mia since its 100th anniversary and is located in south-central Minneapolis, was designed by McKim, Mead & White in 1915; Mia is the largest art museum in the city and has 100,000 pieces in its permanent collection. New wings, which were designed by Kenzo Tange and Michael Graves, opened in 1974 and 2006, respectively; the new wings house contemporary and modern works, and provide additional gallery space.[143]

Frank Gehry designed Weisman Art Museum, which opened in 1993, for the University of Minnesota.[144] A 2011 addition by Gehry doubled the size of the galleries.[145] The Museum of Russian Art opened in a restored church in 2005, and hosts a collection of 20th-century Russian art and special events.[146] Northeast Minneapolis Arts District hosts 400 independent artists, a center at the Northrup-King Building, and recurring annual events.[147]

Theater and performing arts

Minneapolis has hosted theatrical performances since the end of the American Civil War.[148] Early theaters included Pence Opera House,[148] the Academy of Music, Grand Opera House, Lyceum, and later Metropolitan Opera House, which opened in 1894.[149] As of 2020[update], Minneapolis has numerous theater companies.[150]

Guthrie Theater, the area's largest theater company, occupies a three-stage complex that was designed by French architect Jean Nouvel and overlooks the Mississippi River.[143] The company was founded in 1963 by Sir Tyrone Guthrie as a prototype alternative to Broadway, and it produces a wide variety of shows throughout the year.[151][152] Minneapolis purchased and renovated the Orpheum, State, and Pantages Theatres, vaudeville and film houses on Hennepin Avenue that are now used for concerts and plays.[153] Another renovated theater, the Shubert, joined with the Hennepin Center for the Arts to become the Cowles Center for Dance and the Performing Arts, which houses more than 12 performing arts groups.[154][155]

Music

![Recording artist Prince studied at Minnesota Dance Theatre through Minneapolis Public Schools.[156][157]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0d/Prince_by_jimieye-crop.jpg/220px-Prince_by_jimieye-crop.jpg)

Minnesota Orchestra plays classical and popular music at Orchestra Hall under Thomas Søndergård, the music director effective with the 2023–2024 season;[158] The New Yorker critic Alex Ross said of one 2010 special performance at Carnegie Hall, "... the Minnesota Orchestra sounded, to my ears, like the greatest orchestra in the world".[159] The orchestra recorded Casa Guidi, winning a Grammy Award in 2004 for composer Dominick Argento.[160]

Singer and multi-instrumentalist Prince was born in Minneapolis, and lived in the area most of his life.[161] After Jimmy Jam and the 11-piece Mind & Matter broke through discrimination and racial barriers, Prince reached a global, multiracial audience with his combination of rock and funk.[162] Prince, an authentic musical prodigy who was enriched by a music program at The Way Community Center, learned to operate a Polymoog synthesizer at Sound 80 for his first album that became an element of the Minneapolis sound.[163] With fellow local musicians, many of whom recorded at Twin/Tone Records,[164] Prince helped change First Avenue and the 7th Street Entry into prominent venues for artists and audiences.[165]

The city hosts a number of other concert venues, including Icehouse, the Cedar, the Dakota and the Cabooze. Live Nation books The Armory, the Fillmore and the Varsity Theater.[166]

![In 1970, Allan Fingerhut saw the potential for the nightclub that became First Avenue & 7th Street Entry which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2020.[167]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/First_Avenue-Minneapolis-2005-05-18.jpg/220px-First_Avenue-Minneapolis-2005-05-18.jpg)

Hüsker Dü and The Replacements were pivotal in the US alternative rock boom during the 1980s. Their respective frontmen Bob Mould and Paul Westerberg developed successful solo careers.[168] MN Spoken Word Association and independent hip hop label Rhymesayers Entertainment have garnered attention for their rap, hip hop, and spoken word performances and recordings.[169] Underground Minnesota hip hop acts such as Atmosphere and Manny Phesto prominently feature the city and Minnesota in their song lyrics.[170][171] Minneapolis Electronic dance music artists include Woody McBride,[172] Freddy Fresh,[173] and DVS1.[174]

Tom Waits released two songs about the city; "Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis" (Blue Valentine, 1978) and "9th & Hennepin" (Rain Dogs, 1985). Lucinda Williams recorded "Minneapolis" (World Without Tears, 2003). Minneapolis grunge band Babes in Toyland recorded Minneapolism (2001).[175] In 2008, the century-old MacPhail Center for Music opened a new facility that was designed by James Dayton.[176] Minneapolis's opera companies are Minnesota Opera, Mill City Summer Opera, the Gilbert & Sullivan Very Light Opera Company, and Really Spicy Opera.[177]

Museums

Exhibits at Mill City Museum feature the city's history of flour milling, and Minnehaha Depot was built in 1875.[178] The American Swedish Institute occupies a former mansion on Park Avenue.[179] The American Indian Cultural Corridor, about eight blocks on Franklin Avenue, houses All My Relatives Gallery.[180] On Penn Avenue North is Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery which was founded in 2018.[181] In a former mansion one block from Mia is Hennepin History Museum.[182] On East Lake Street is the world's only Somali history museum, the tiny Somali Museum of Minnesota.[183] The Bakken, which was formerly known as Museum of Electricity in Life, shifted focus in 2016 from electricity and magnetism to invention and innovation, and in 2020 opened a new entrance on Bde Maka Ska.[184]

Charity

Philanthropy and charitable giving have been part of the Minneapolis community since the 1800s.[185] As of 2022[update], Alight helps 2.5 million refugees and displaced persons each year in developing countries in Africa and Asia.[186] Catholic Charities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul is one of the largest non-profit organizations in the state, and a provider of several social services.[187] The Minneapolis Foundation invests and administers over 1,000 charitable funds.[188] According to AmeriCorps, in 2017, Minneapolis–Saint Paul, with 46.3% of the population volunteering, had the highest proportion of volunteers among US cities.[189]

Literary arts

The nonprofit literary presses Coffee House Press, Milkweed Editions, and Graywolf Press are based in Minneapolis.[190] Also internationally known, University of Minnesota Press publishes books, journals, and a widely used personality test, the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory.[191] Open Book, Minnesota Center for Book Arts, and The Loft Literary Center are located in Minneapolis.[192]

Cuisine

West Broadway Avenue was a cultural center during the early 20th century, but by the 1950s flight to the suburbs began and streetcar service ended citywide.[193] One of the largest urban food deserts in the US was in the north side of Minneapolis, where as of mid-2017, 70,000 people had access to only two grocery stores.[194] Wirth Co-op opened in 2017 but closed within a year. North Market opened in 2017.[195][196] The nonprofit Appetite for Change sought to improve the local diet, competing against an influx of fast-food stores,[197] and by 2017 it administered 10 gardens, sold produce in the mid-year months at West Broadway Farmers Market, supplied its restaurants, and gave away boxes of fresh produce.[198]

Many Minneapolis-based individuals have won James Beard Foundation Awards, including writer Dara Moskowitz Grumdahl, and chef Sean Sherman, whose restaurant, Owamni, received James Beard's 2022 national award for "best new restaurant".[199][200][201]

Both credible originators of the burger, the 5-8 Club and Matt's Bar have served the Jucy Lucy since the 1950s.[202] The United States' first vegan butcher shop, The Herbivorous Butcher, opened in 2016.[203] East African cuisine arrived in Minneapolis with the wave of migrants from Somalia that started in the 1990s.[204] Gavin Kaysen and others on Team USA won a silver medal in the 2015 Bocuse d'Or.[205]

Annual events

Each January and February, a series of events called The Great Northern is held in Minneapolis. The series includes the U.S. Pond Hockey Championships; the City of Lakes Loppet, a 22-mile (35 km) cross-country ski race; and the Saint Paul Winter Carnival.[206] The annual MayDay Parade returned in 2021 following the COVID-19 pandemic; other events include Art-A-Whirl; Pride Festival & Parade, Stone Arch Bridge Festival, and Twin Cities Juneteenth Celebration in June; Minneapolis Aquatennial in July; Minnesota Fringe Festival, Loring Park Art Festival, Metris Uptown Art Fair, Powderhorn Festival of Arts and the Lake Hiawatha Neighborhood Festival in August; Minneapolis Monarch Festival in September that celebrates the Monarch butterfly's 2,300-mile (3,700 km) migration; and the Twin Cities Marathon in October.[207]

Libraries

The Minneapolis Public Library, which was founded by T. B. Walker in 1885,[208] merged with the Hennepin County Library system in 2008.[209] Fifteen branches of the Hennepin County Library serve Minneapolis.[210] The new downtown Central Library designed by César Pelli opened in 2006.[211] Ten special collections hold over 25,000 books and resources for researchers, including the Minneapolis Collection and the Minneapolis Photo Collection.[212]

Sports

| Team | Sport | League | Since | Venue (capacity) | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minnesota Lynx | Basketball | Women's National Basketball Association | 1999 | Target Center (18,798) | 2011, 2013, 2015, 2017 |

| Minnesota Timberwolves | Basketball | National Basketball Association | 1989 | Target Center (18,798) | |

| Minnesota Twins | Baseball | Major League Baseball | 1961 | Target Field (39,500) | 1987, 1991 |

| Minnesota Vikings | American football | National Football League | 1961 | U.S. Bank Stadium (66,655)[213] | 1969 (NFL) |

Minneapolis has four professional sports teams. The American football team Minnesota Vikings and the baseball team Minnesota Twins have played in the state since 1961. The Vikings were an National Football League (NFL) expansion team and the Twins were formed when the Washington Senators relocated to Minnesota.[214] The Twins won the World Series in 1987 and 1991, and have played at Target Field since 2010. The Vikings played in the Super Bowl following the 1969, 1973, 1974, and 1976 seasons, losing all four games. The basketball team Minnesota Timberwolves returned National Basketball Association (NBA) basketball to Minneapolis in 1989, and were followed by Minnesota Lynx in 1999. Both basketball teams play in the Target Center.

In the 2010s, the Lynx were the most-successful sports team in the city and a dominant force in the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA), reaching the WNBA finals in 2011, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016, and 2017, and winning in 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017.[215] In 2016, following the killings of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling, Lynx captains wore black shirts as a protest by Black athletes for social change.[216]

In addition to professional sports teams, Minneapolis also hosts a majority of the Minnesota Golden Gopher college sports teams of the University of Minnesota. The Gophers football team plays at Huntington Bank Stadium and have won national championships in 1904, 1934, 1935, 1936, 1940, 1941, and 1960.[217] The Gophers women's ice hockey team plays at Ridder Arena and is a six-time NCAA champion, and were the national champion in 2000, 2004, 2005, 2012, 2013, 2015, and 2016.[218][219] The Gophers men's ice hockey team plays at 3M Arena at Mariucci, and won NCAA national championships in 1974, 1976, 1979, 2002, and 2003.[220] Both the Golden Gophers men's basketball and women's basketball teams play at Williams Arena.

The 1,750,000-square-foot (163,000 m2) U.S. Bank Stadium was built for the Vikings at a cost of $1.122 billion, $348 million of which was provided by the state of Minnesota and $150 million came from the city of Minneapolis. The stadium, which was called "Minnesota's biggest-ever public works project", opened in 2016 with 66,000 seats, which was expanded to 70,000 for the 2018 Super Bowl.[221] U.S. Bank Stadium also hosts indoor running and rollerblading nights, concerts, and other events.[222]

The city hosts some major sporting events, including baseball All-Star Games, World Series, Super Bowls, NCAA Division 1 men's and women's basketball Final Four, the AMA Motocross Championship, the X Games, and the WNBA All-Star Game.[223]

Minnesota Wild, an National Hockey League team, play at the Xcel Energy Center;[224] and the Major League Soccer soccer team Minnesota United FC play at Allianz Field, both of which are located in Saint Paul.[225] Six golf courses are located within Minneapolis' city limits.[226] While living in Minneapolis, Scott and Brennan Olson founded and later sold Rollerblade, the company that popularized the sport of inline skating.[227]

The Twin Cities Marathon is a Boston Marathon qualifier.[228]

Parks and recreation

![Established in 1889, Minnehaha Falls and the surrounding land was one of the country's first state parks.[229]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Minnehaha_Falls%2C_Minneapolis.jpg/220px-Minnehaha_Falls%2C_Minneapolis.jpg)

In his book The American City: What Works, What Doesn't, Alexander Garvin wrote Minneapolis built "the best-located, best-financed, best-designed, and best-maintained public open space in America".[230]

The city's parks are governed and operated by the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board, an independent park district with broader powers than any other parks agency in the US.[231] Foresight, donations, and effort by community leaders enabled Horace Cleveland to create his finest landscape architecture, preserving geographical landmarks and linking them with boulevards and parkways.[232] The city's Chain of Lakes, consisting of seven lakes and Minnehaha Creek, is connected by bicycle paths, and running and walking paths, and are used for swimming, fishing, picnics, boating, and ice skating. A parkway for cars, a bikeway for riders, and a walkway for pedestrians run parallel along the 52-mile (84 km) route of the Grand Rounds National Scenic Byway.[233] Theodore Wirth is credited with developing the parks system.[234] Approximately 15 percent of land in Minneapolis is parks, in accordance with the 2020 national median, and 98 percent of residents live within one-half mile (0.8 km) of a park.[235]

Parks are interlinked in many places, and the Mississippi National River and Recreation Area connects regional parks and visitor centers. The country's oldest public wildflower garden, the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden and Bird Sanctuary, is located within Theodore Wirth Park, which is shared with Golden Valley and is about 90 percent of the area of Central Park, New York City.[236] Minnehaha Park contains the 53-foot (16 m) waterfall Minnehaha Falls, and is one of the city's oldest and most popular parks.[237] The regional park received over 2,050,000 visitors in 2017.[238] In the bestselling and often-parodied 19th-century epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow named Hiawatha's wife Minnehaha for the Minneapolis waterfall.[239] The five-mile (8 km), hiking-only Winchell Trail runs along the Mississippi River, and offers views of and access to the Mississippi Gorge and a rustic hiking experience.[240]

Minneapolis's climate provides opportunities for winter activities such as ice fishing, snowshoeing, ice skating, cross-country skiing, and sledding at many parks and lakes between December and March.[241] When there is sufficient snowfall or in the presence of snowmaking, a partnership between the park board and Loppet Foundation provides for the grooming of 20 miles (32 km) of cross-country ski trails between Wirth Park, the Chain of Lakes, and two of the city's golf courses.[242][243][241] The City of Lakes Loppet cross-country ski race is part of the American ski marathon series.[244] The park board maintains 20 outdoor ice rinks in winter[245] and the city's Lake Nokomis is host to the annual U.S. Pond Hockey Championships.[246]

Government

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 11.3% 26,792 | 86.4% 204,841 | 2.3% 5,344 |

| 2016 | 11.8% 25,693 | 79.8% 174,585 | 8.4% 18,380 |

| 2012 | 16.5% 35,560 | 80.3% 172,480 | 3.2% 6,839 |

| 2008 | 16.8% 34,958 | 81.1% 169,204 | 2.1% 4,352 |

| 2004 | 20.7% 41,633 | 77.6% 156,214 | 1.7% 3,366 |

| 2000 | 22.3% 38,865 | 66.3% 115,566 | 11.4% 19,852 |

| 1996 | 21.1% 31,571 | 70.9% 106,241 | 8.0% 12,089 |

| 1992 | 19.9% 36,528 | 63.6% 116,696 | 16.5% 30,142 |

| 1988 | 29.9% 53,859 | 70.1% 126,506 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1984 | 34.1% 67,279 | 65.9% 130,225 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1980 | 27.9% 54,134 | 57.0% 110,545 | 15.1% 29,178 |

| 1976 | 34.6% 67,969 | 62.5% 122,619 | 2.9% 5,729 |

| 1972 | 42.8% 80,015 | 55.3% 103,407 | 1.9% 3,728 |

| 1968 | 36.1% 70,016 | 59.1% 114,721 | 4.8% 9,432 |

| 1964 | 34.1% 72,383 | 65.6% 139,275 | 0.3% 576 |

| 1960 | 47.4% 107,044 | 52.3% 118,143 | 0.3% 588 |

| 1956 | 51.5% 109,726 | 48.3% 102,991 | 0.2% 370 |

Minneapolis is currently a majority holding for the Minnesota Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party (DFL), an affiliate of the Democratic Party, and had its last Republican mayor in 1973.[248] DFL council member Jacob Frey was elected mayor of Minneapolis in 2017, and was re-elected in 2021.[249] In 2021, a ballot question shifted more power from the city council to the mayor,[250] a change that proponents had tried to achieve since the early 20th century.[251] Parks, taxation, and public housing are semi-independent boards that levy their own taxes and fees, which are subject to Board of Estimate and Taxation limits.[252]

The Minneapolis City Council represents the city's 13 wards. The city adopted instant-runoff voting in 2006, first using it in the 2009 elections.[253] The council is progressive; it has 12 DFL council members and one from the Democratic Socialists of America.[254] Andrea Jenkins was unanimously chosen as president of the City Council in 2022.[255] In 2022, the 13-member council has seven political newcomers and for the first time has a majority of non-White council members.[255]

At the federal level, Minneapolis is within Minnesota's 5th congressional district, which since 2018 has been represented by Democrat Ilhan Omar, one of the first two practicing Muslim women and the first Somali-American in Congress. Minnesota's US Senators, Amy Klobuchar and Tina Smith, were elected or appointed while living in Minneapolis, and are also Democrats.[256]

In 2015, the City Council passed a resolution making fossil fuel divestment city policy,[257] joining 17 cities worldwide in the Carbon Neutral Cities Alliance. Minneapolis' climate plan calls for an 80 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.[258] Minneapolis has a separation ordinance that directs local law-enforcement officers not to "take any law enforcement action" for the sole purpose of finding undocumented immigrants, nor to ask an individual about his or her immigration status.[259]

Frey's biennial budget is open for public comment, proposing $1.66 billion in 2023 and $1.71 billion in 2024, overall an $80 million increase. The source of funding would be a 6.5 percent property tax increase in 2023, and 6.2 percent in 2024.[260] The city council is scheduled to vote on its adoption in December 2022.[261] The US Justice Department [262] and the Minnesota Department of Human Rights.[263] have been investigating policing practices in Minneapolis. The proposed budget plans for one negotiated consent decree and 731 police officers in 2023,[260] aligned with a Minnesota Supreme Court decision.[264]

After the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, about 166 police officers left of their own accord either to retirement or to temporary leave—many with PTSD[265]—and a crime wave resulted in more than 500 shootings.[266] A Reuters investigation found that killings surged when a "hands-off" attitude resulted in fewer officer-initiated encounters.[267] As of July 2022, violent crime rose about 3% across Minneapolis compared with 2021,[268] and in 2020, it rose 21%.[269]

A 2021 ballot question to abolish the police department failed. However the restructured mayor's role created a new Minneapolis Office of Community Safety, and in 2022, Cedric Alexander became its first commissioner, overseeing the police and fire departments, 911 dispatch, emergency management, and violence prevention. He is the city's highest paid employee, earning more than twice the mayor's salary.[270]

The city in 2021 proposed a new cooperation with the police department and a mental health services company, Canopy Mental Health & Consulting, to respond to some 911 calls that do not require police.[271] The organization has responded to more than three thousand 911 calls as of September 2022 and is proposed to continue through the 2023-2024 budget year.[272]

Education

Primary and secondary education

Minneapolis Public Schools enroll over 35,000 students in public primary and secondary schools. The district administers about 100 public schools, including 45 elementary schools, seven middle schools, seven high schools, eight special education schools, eight alternative schools, nineteen contract alternative schools, and five charter schools. With authority granted by the state legislature, the school board makes policy, selects the superintendent, and oversees the district's budget, curriculum, personnel, and facilities. In 2017, the graduation rate was 66 percent.[273] Students speak over 100 languages at home and most school communications are printed in English, Hmong, Spanish, and Somali.[274][275] Some students attend public schools in other school districts chosen by their families under Minnesota's open enrollment statute.[276] Besides public schools, the city has more than 20 private schools and academies, and about 20 additional charter schools.[277]

Colleges and universities

Minneapolis's collegiate scene is dominated by the main campus of the University of Minnesota, where more than 50,000 undergraduate, graduate, and professional students attend 20 colleges, schools, and institutes.[278] The university offers free tuition to students from Minnesota families earning less than $50,000 per year.[279] The graduate school programs with exceptional, top-five national rankings in 2020 were health care management, nursing, midwifery, pharmacy, and clinical psychology.[280] The university has unusual constitutional autonomy that has existed in three US states since 1851, when the provision was included in Minnesota's constitution.[281]

Augsburg University, Minneapolis College of Art and Design, and North Central University are private four-year colleges. Minneapolis Community and Technical College and the private Dunwoody College of Technology provide career training. St. Mary's University of Minnesota has a Twin Cities campus for its graduate and professional programs. The large, principally online universities Capella University and Walden University are both headquartered in the city. The public four-year Metropolitan State University and the private four-year University of St. Thomas are among post-secondary institutions based elsewhere that have campuses in Minneapolis.[282]

Media

Several newspapers are published in Minneapolis; Star Tribune, Finance & Commerce, Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, the university's The Minnesota Daily, and MinnPost.com. TMC Publications publishes The Monitor, Longfellow Nokomis Messenger and the Southwest Connector.[283] MSP Communications publishes Mpls.St.Paul and Twin Cities Business magazines.[284] Other publications include Minnesota Women's Press, North News, Northeaster, Insight News, The Circle, Southwest Voices,[283] and Dispatch.[285]

Nineteen FM and AM radio stations are licensed to Minneapolis, including one from the University of Minnesota and one from the public schools. Up to 79 FM and AM signals can be received in one or more areas of the city. There are 10 full-power television stations in the metro area, and one non-profit public-access cable network. WCCO-TV is based in Minneapolis proper. A majority of these signals can be streamed.[286]

Krista Tippett, winner of a Peabody Award and the National Humanities Medal, produces the On Being project from her studio across Hennepin from the basilica. In 2022, she changed her show from weekly radio to seasonal podcasts.[287]

Movies filmed in Minneapolis include Airport (1970),[288] The Heartbreak Kid (1972),[289] Slaughterhouse-Five (1972),[290] Ice Castles (1978),[291] Foolin' Around (1980),[292] Take This Job and Shove It (1981),[293] Purple Rain (1984),[294] That Was Then, This Is Now (1985),[295] The Mighty Ducks (1992),[296] Untamed Heart (1993),[297] Little Big League (1994),[298] Beautiful Girls (1996),[299] Jingle All the Way (1996),[300] Fargo (1996),[301] and Young Adult (2011).[302] In 1960s television, two episodes of Route 66 were made in Minneapolis. The 1970s CBS situation comedy set in Minneapolis, The Mary Tyler Moore Show, won three Golden Globes[303] and 29 Emmy Awards.[304] The show's opening sequences were filmed in the city.[305]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Minneapolis has two light rail lines and one commuter rail line. The Metro Blue Line connects the Mall of America and Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport in Bloomington to downtown, and the Metro Green Line travels east from downtown through the University of Minnesota campus to downtown Saint Paul. Hundreds of homeless people nightly sought shelter on Green Line trains until overnight service was cut back in 2019. In 2020, a rise in crime on the light rail system led to discussion in the state legislature on how to best address the problem.[306][307] An extension of the Green Line that will connect downtown Minneapolis with the southwestern suburbs is expected to open in 2023.[308] An extension of the Blue Line to the northwest suburbs re-entered the planning stages for a new route alignment in 2020.[309] The 40-mile (64 km) Northstar Commuter rail runs from Big Lake through the northern suburbs and terminates at the multi-modal transit station at Target Field using existing railroad tracks.[310] Public transit ridership in the Twin Cities was 91.6 million in 2019, a three-percent decline over the previous year, which is part of a national trend in falling local bus ridership. Ridership on the Metro system remained steady or grew slightly.[311]

In 2007, the Interstate 35W bridge over the Mississippi, which was overloaded with 300 short tons (270,000 kg) of repair materials, collapsed, killing 13 people and injuring 145. The bridge was rebuilt in 14 months. Only one quarter of the US's structurally deficient bridges had been repaired ten years later.[312]

The Minneapolis Skyway System, 9.5 miles (15.3 km) of enclosed pedestrian bridges called skyways, links 80 city blocks downtown with second-floor restaurants and retailers that are open on weekdays.[313] Minneapolis has 82 miles (132 km) of trails for walking and biking.[314] Off-street facilities include the Grand Rounds Scenic Byway, Midtown Greenway, Little Earth Trail, Hiawatha LRT Trail, Kenilworth Trail, and Cedar Lake Trail.[315] Bicycle-sharing provider Nice Ride Minnesota planned expanded capacity in 2019.[316]

Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport (MSP) is served by 18 international, domestic, charter, and regional carriers, and is the headquarters of Sun Country Airlines.[317] As of 2019, MSP is also the second-largest hub for Delta Air Lines, which operates more flights out of MSP than any other airline.[318]

Health care

Abbott Northwestern Hospital, University of Minnesota Medical Center, Hennepin Healthcare, Minneapolis VA Medical Center, Shriners Hospitals for Children, Children's Hospitals and Clinics, University of Minnesota Masonic Children's Hospital, and Phillips Eye Institute serve the city.[319] The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, is 87 miles (140 km) from Minneapolis.[320]

Cardiac surgery was developed at the university's Variety Club Hospital, where by 1957, more than 200 patients—many of whom were children—had survived open-heart operations. Working with surgeon C. Walton Lillehei, Medtronic began to build portable and implantable cardiac pacemakers about this time.[321]

Hennepin Healthcare, a public teaching hospital and Level I trauma center, opened in 1887 as City Hospital, and has also been known as Minneapolis General Hospital, Hennepin County General Hospital, and HCMC.[322][323] The Hennepin Healthcare safety net counted 643,739 clinic visits, and 111,307 emergency and urgent care visits in 2019.[324]

The Mashkiki Waakaa'igan Pharmacy on Bloomington Avenue dispenses free prescription drugs and culturally sensitive care to members of any federally recognized tribes living in Hennepin and Ramsey counties, regardless of insurance status.[325] The pharmacy has nearly 10,000 registered patients and is funded by the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.[325]

Utilities

"Ambassadors", who are identified by their blue-and-green-yellow fluorescent jackets, daily patrol a 120-block area of downtown to greet and assist visitors, remove trash, monitor property, and call police when they are needed. The ambassador program is a public-private partnership with a $6.6 million annual budget that is paid for by a special downtown tax district.[326]

Xcel Energy supplies electricity, CenterPoint Energy supplies gas, CenturyLink provides landline telephone service, and Comcast provides cable service.[327] The city treats and distributes water, and charges a monthly fee for trash removal.[328]

After each significant snowfall, called a snow emergency, the Minneapolis Public Works Street Division plows over 1,000 miles (1,609.3 km) of streets and 400 miles (643.7 km) of alleys—counting both sides, the distance between Minneapolis and Seattle and back.[329] Ordinances govern parking on plowing routes during these emergencies, as well as snow shoveling.[330]

Notable people

Sister cities

Minneapolis's sister cities are:[331]

See also

- List of events and attractions in Minneapolis

- List of tallest buildings in Minneapolis

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Hennepin County, Minnesota

Notes

- The University of Minnesota Dakota Dictionary Online requires a Dakota font to read special characters.[6] Here, Dakota to Latin alphabet transliteration is borrowed from Lerner Publishing in Minneapolis.[7]

- In Atwater's history, the Sioux word given is Minne.[18] Riggs gives mini.[19] Williamson who was most familiar with Santee has Mini, and in the Yankton dialect, mni.[20] Here, mni is from the University of Minnesota Dakota Dictionary Online.[21]

- E. K. Soper, writing in 1915 before Minneapolis had reached its present size, described "several points which attain an altitude of 965 feet [294 m], or thereabouts" near the border with Columbia Heights.[70] In a 1975 article, reporter John Carman said the city's highest point is 967 feet (295 m) at Deming Heights Park in the Waite Park neighborhood .[71] The United States Geological Survey (USGS) lists the highest elevation as 980 feet (300 m) but does not give a location.[69] Geography professor John Tichy said the highest point is the site of Waite Park Elementary School at approximately 985 feet (300 m) above sea level.[72] All of the cited sources that list locations say the highest point is within Northeast section of the city.

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e., the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- Official records for Minneapolis/St. Paul were kept by the St. Paul Signal Service in that city from January 1871 to December 1890, the Minneapolis Weather Bureau from January 1891 to April 8, 1938, and at KMSP since April 9, 1938.[85]

References

- Swanson, Kirsten (November 5, 2021). "Voters approve charter amendment to change Minneapolis government structure". KSTP-TV. Hubbard Broadcasting. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021". United States Census Bureau. May 29, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". US Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Bdeota O™uåwe". University of Minnesota Dakota Dictionary Online. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall and Smith, Monique Gray (2022). Braiding Sweetgrass for Young Adults. Lerner Publishing Group. p. 304. ISBN 9781728460659 – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Lass, William E. (1980). Minnesota's Boundary with Canada: Its Evolution Since 1783. Minnesota Historical Society. pp. 14–17. ISBN 978-0873511537.

- Watson, Catherine (September 16, 2012). "Ft. Snelling: Citadel on a Minnesota bluff". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- Wingerd, Mary Lethert (2010). North Country: The Making of Minnesota. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 4, 5, 33, 82, 159. ISBN 978-0816648689.

- "Historic Fort Snelling: The US Indian Agency (1820–1853)". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- Anderson 2019, pp. 32–33. Anderson examined the Dousman Papers to formulate estimates of the funds that were diverted to White officials.

- "Treaties". The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. July 31, 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- Anderson 2019, pp. 32–33.

- Anderson 2019, p. 55: "...they had to beg for food from the settlers or starve".

- "Treaties". July 31, 2012. and "Forced Marches & Imprisonment". August 23, 2012. and "Aftermath". Minnesota Historical Society. July 3, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- "John H. Stevens House Museum". US National Park Service. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- Atwater, Isaac, ed. (1893). "Early Settlement". History of the City of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Vol. 1. Munsell & Company. p. 39. OCLC 22047580 – via Internet Archive.

- Riggs, Stephen Return and Dorsey, James Owen (1992) [1st pub. Government Printing Office, 1890]. A Dakota-English dictionary. Minnesota Historical Society Press – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Williamson, John P., A.M. D.D. (compiler) (1902). An English-Dakota Dictionary. American Tract Society – via Google Books.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "mni". University of Minnesota Dakota Dictionary Online. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- Christianson, Theodore (1935). Minnesota: The Land of Sky-tinted Waters: A History of the State And Its People. Chicago: American Historical Society. Courtesy Star Tribune and the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library, in McKinney, Matt (August 19, 2022). "How did Stillwater become home to Minnesota's first prison?". Star Tribune. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- Baldwin, Rufus J.; Atwater, Isaac (1893). "Early Settlement," "History and Incidents of Banking," and "Pioneer Life in Minneapolis—From a Woman's Standpoint". In Atwater, Isaac (ed.). History of the City of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Vol. 1. Munsell & Company. pp. 29–48, 80, 498 [39]. OCLC 22047580. and Johnston, Daniel S. B. (1905). "Minnesota Journalism in the Territorial Period". Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. Vol. 10. Minnesota Historical Society. pp. 261–262. OCLC 25378013. and Parsons, Ernest Dudley (1913). The Story of Minneapolis. Minneapolis: Colwell Press. pp. 52–53 – via Google Books.

- "A History of Minneapolis: Mdewakanton Band of the Dakota Nation, Parts I and II". Hennepin County Library. 2001. Archived from the original on April 9, 2012. and "The US-Dakota War of 1862". Minnesota Historical Society. and "A History of Minneapolis: Minneapolis Becomes Part of the United States". Archived from the original on April 21, 2012., and "A History of Minneapolis: Governance and Infrastructure". Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. and "A History of Minneapolis: Railways". Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Frame, Robert M., III; Hess, Jeffrey (January 1990). "Historic American Engineering Record MN-16: West Side Milling District" (PDF). U.S. National Park Service. p. 2. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- Hart, Joseph (June 11, 1997). "Lost City". City Pages. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Anfinson, Scott F. (1990). "Archaeology of the Central Minneapolis Riverfront Part 2: Archaeological Explorations and Interpretive Potentials, Chapter 4". The Minnesota Archaeologist. 49 (1–2). Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- Watts, Alison (Summer 2000). "The technology that launched a city: scientific and technological innovations in flour milling during the 1870s in Minneapolis" (PDF). Minnesota History. 57 (2): 86–97. JSTOR 20188202. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Danbom, David B. (2003). "Flour power: the significance of flour milling at the falls" (PDF). Minnesota History. 58 (5–6): 270–285. JSTOR 20188363. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- "Crown Roller Mill: HAER No. MN-12" (PDF). Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record. US Library of Congress. p. 10. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- Lamm Carroll, Jane (October 27, 2015). "Engineering the Falls: The Corps of Engineers' Role at St. Anthony Falls". St. Paul District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- Nestle, Marion; Nesheim, Malden C. (2010). Feed Your Pet Right. Free Press (Simon & Schuster). pp. 322–323. ISBN 978-1-4391-6642-0. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- "History". Mill City Museum. Archived from the original on May 13, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- Gray, James (1954). Business without Boundary: The Story of General Mills. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 33–34, 41. LCCN 54-10286.

- Atwater, Isaac (1893). History of the City of Minneapolis, Minnesota. Munsell. pp. 257–262. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- Nathanson 2010, pp. 41–47.

- Nathanson, Iric (December 2, 2013). "Goodwin's 'The Bully Pulpit' spotlights the Shame of Minneapolis". MinnPost. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- Waxman, Olivia B. (June 2, 2020). "George Floyd's Death and the Long History of Racism in Minneapolis". Time.com.

Delegard told TIME, 'Structural racism is really baked into the geography of this city and as a result it really permeates every institution in this city.'

and Mattke, Ryan (June 11, 2018). "Join us for 'Racism, Rent and Real Estate: Fair Housing Reframed'". Regents of the University of Minnesota. Retrieved November 17, 2022....our dark history of covenants, redlining and structural racism...

- "Goals: 1. Eliminate disparities". Minneapolis2040.com. Department of Community Planning & Economic Development: City of Minneapolis. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

...in 2010, Minneapolis led the nation in having the widest unemployment disparity between African-American and white residents. This remains true in 2018. And disparities also exist in nearly every other measurable social aspect, including of economic, housing, safety and health outcomes, between people of color and indigenous people compared with white people." and "In Minneapolis, 83 percent of white non-Hispanics have more than a high school education, compared with 47 percent of black people and 45 percent of American Indians. Only 32 percent of Hispanics have more than a high school education.

- Holder, Sarah (June 5, 2020). "Why This Started in Minneapolis". Bloomberg CityLab. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- Furst, Randy; Webster, MaryJo (September 6, 2019). "How did Minn. become one of the most racially inequitable states?". Star Tribune. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

The privileges of whites go back much further ... to when American Indians were forced off their land in the 1860s.

- Weber 2022, pp. 84, 88.

- About 10,000 such covenants remained as of 2017, in: Furst, Randy (August 26, 2017). "Massive project works to uncover racist restrictions in Minneapolis housing deeds". Star Tribune. and Delegard, Kirsten; Ehrman-Solberg, Kevin (2017). "'Playground of the People'? Mapping Racial Covenants in Twentieth-century Minneapolis". Open Rivers: Rethinking the Mississippi. 6. doi:10.24926/2471190X.2820.

- Navratil, Liz (March 3, 2021). "Minneapolis starts program to disavow racial covenants". Star Tribune. and "City Attorney's Office: Just Deeds". City of Minneapolis. March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- Hatle, Elizabeth Dorsey; Vaillancourt, Nancy M. (Winter 2009–2010). "One Flag, One School, One Language: Minnesota's Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s" (PDF). Minnesota History. 61 (8): 360–371. JSTOR 40543955. and Chalmers, David Mark (1987). Hooded Americanism: The History of the Ku Klux Klan. Duke University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8223-0772-3. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- Nathanson 2010, p. 58.

- Ladd-Taylor, Molly (Summer 2005). "Coping with a 'Public Menace': Eugenic Sterilization in Minnesota" (PDF). Minnesota History. 59 (6): 237–248. JSTOR 20188483. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Anti-Semitism in Minneapolis". carleton.edu. Religions in Minnesota. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- Weber, Laura E. (Spring 1991). "'Gentiles Preferred': Minneapolis Jews and Employment 1920–1950" (PDF). Minnesota History. 52 (5): 166–182. JSTOR 20179243. Retrieved August 21, 2012.

- "A History of Minneapolis: Medicine". Hennepin County Library. 2001. Archived from the original on April 21, 2012. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- "Truckers' Strike of 1934: Overview". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Reichard, Gary W. (Summer 1998). "Mayor Hubert H. Humphrey" (PDF). Minnesota History. 56 (2): 50–67. JSTOR 20188091. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- Nathanson 2010, "Chapter 4: Plymouth Avenue Is Burning".

- Nathanson 2010, pp. 126–130.

- [dead link] Harry Davis (February 21, 2003). Almanac. Twin Cities Public Television. and Davis, Julie L. (2013). Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8166-7429-9.

- Weber 2022, p. 128.

- Hart, Joseph (May 6, 1998). "Room at the Bottom". City Pages. Vol. 19, no. 909. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- Taylor, Derrick Bryson (July 10, 2020). "George Floyd Protests: A Timeline". The New York Times. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- Stockman, Farah (July 3, 2020). "'They Have Lost Control': Why Minneapolis Burned". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- Caputo, Angela; Craft, Will; Gilbert, Curtis (June 30, 2020). "'The precinct is on fire': What happened at Minneapolis' 3rd Precinct—and what it means". MPR News. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- MPR News Staff (August 24, 2020). "NPR special report: Summer of racial reckoning". MPR News. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- "Lake Calhoun signs updated to include the lake's Dakota name, Bde Maka Ska". MPR News. October 3, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- Wright, H. E. Jr. (1990). "Geologic History of Minnesota Rivers" (PDF). Minnesota Geological Survey Educational Series. 7: 3–4, 14. Retrieved November 16, 2020 – via South Washington Watershed District.

- Fremling, Calvin R. (2005). Immortal River: The Upper Mississippi in Ancient and Modern Times. University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 56–60. ISBN 9780299202941.

- "Minneapolis". emporis.com. Emporis Buildings. Archived from the original on April 23, 2007. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- "Physical Environment". City of Minneapolis. p. 39. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- "State of the City: Physical Environment" (PDF). Minneapolis Planning Division via Internet Archive. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 8, 2008. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- Harms, G. F. (October 1959). Soil Survey of Scott County, Minnesota (PDF) (Report). Soil Conservation Service. p. 59. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. April 29, 2005. Archived from the original on January 16, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- Soper, E. K. (1915). "The Buried Rock Surface and Pre-Glacial River Valleys of Minneapolis and Vicinity". The Journal of Geology. 23 (5): 444–460. Bibcode:1915JG.....23..444S. doi:10.1086/622258.

- Carman, John (September 8, 1975). "Twin Cities: Different as night and day". Minneapolis Star. pp. 1B, 5B. Retrieved January 17, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Tichy, John (July 18, 1996). "Waite Park School sits on Minneapolis' highest point". Star Tribune. p. E17. Retrieved January 17, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Neighborhoods". City of Minneapolis. and "Council Wards". City of Minneapolis. Retrieved November 12, 2020.