world.wikisort.org - Canada

Brantford (2021 population: 104,688[1]) is a city in Ontario, Canada, founded on the Grand River in Southwestern Ontario. It is surrounded by Brant County, but is politically separate with a municipal government of its own that is fully independent of the county's municipal government.[4][5][6]

Brantford

Tsi kanatáher (Mohawk) | |

|---|---|

City (single-tier) | |

| City of Brantford | |

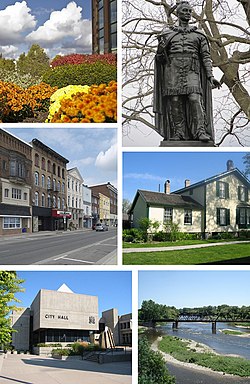

From top, left to right: Flowerbed outside RBC Building, Statue of Joseph Brant, Colborne Street in Downtown Brantford, Bell Homestead, City Hall, Grand River | |

Logo | |

Brantford | |

| Coordinates: 43°08′27″N 80°15′47″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| County | Brant (independent) |

| Established | May 31, 1877 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Kevin Davis |

| • Governing Body | Brantford City Council |

| • MP | Larry Brock (Conservative) |

| • MPP | Will Bouma (Progressive Conservative) |

| Area | |

| • Land | 98.65 km2 (38.09 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,074.00 km2 (414.67 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 248 m (814 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • City (single-tier) | 104,688 (53rd) |

| • Density | 1,061.2/km2 (2,748/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 144,162 (30th) |

| • Metro density | 134.2/km2 (348/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Forward sortation area | N3P to N3V |

| Area code(s) | 519, 226, and 548 |

| GDP (Brantford CMA) | CA$5.3 billion (2016)[3] |

| GDP per capita (Brantford CMA) | CA$39,507 (2016) |

| Website | www.brantford.ca |

Brantford is situated on the Haldimand Tract,[7][8] traditional territory of the Neutral, Mississauga, and Haudenosaunee peoples.[9][10] The city is named after Joseph Brant, an important Mohawk leader, soldier, farmer and slave owner.[11] Brant was an important Loyalist leader during the American Revolutionary War and later, after the Haudenosaunee moved to the Brantford area in Upper Canada. Many of his descendants, and other First Nations people, live on the nearby Six Nations of the Grand River reserve south of Brantford; it is the most populous reserve in Canada.

Brantford is known as the "Telephone City" as the city's famous resident, Alexander Graham Bell, invented the first telephone at his father's homestead, Melville House, now the Bell Homestead, located on Tutela Heights south of the city. Brantford is also known as birthplace and hometown of Wayne Gretzky.

History

The Iroquoian-speaking Attawandaron, known in English as the Neutral Nation, lived in the Grand River valley area before the 17th century; their main village and seat of the chief, Kandoucho, was identified by 19th-century historians as having been located on the Grand River where present-day Brantford developed. This community, like the rest of their settlements, was destroyed when the Iroquois declared war in 1650 over the fur trade and exterminated the Neutral nation.[12]

In 1784, Captain Joseph Brant and the Mohawk people of the Iroquois Confederacy left New York State for Canada.[13] As a reward for their loyalty to the British Crown, they were given a large land grant, referred to as the Haldimand Tract, on the Grand River. The original Mohawk settlement was on the south edge of the present-day city at a location favourable for landing canoes. Brant's crossing (or fording) of the river gave the original name to the area: Brant's ford The Glebe Farm Indian Reserve exists at the original site today.

The area began to grow from a small settlement in the 1820s as the Hamilton and London Road was improved. By the 1830s, Brantford became a stop on the Underground Railroad, and a sizable number of runaway African-Americans settled in the town.[14] From the 1830s to the 1860s - several hundred people of African descent settled in the area around Murray Street, and in Cainsville. In Brantford, they established their own school and church, now known as the S.R. Drake Memorial Church.[15] In 1846, it is estimated 2000 residents lived in the city's core while 5199 lived in the outlying rural areas.[16] There were 8 churches in Brantford at this time - Episcopal, Presbyterian, Catholic, two Methodist, Baptist, Congregational, and one for the African-Canadian residents.[16]

By 1847, Europeans began to settle further up the river at a ford in the Grand River and named their village Brantford.[17] The population increased after 1848 when river navigation to Brantford was opened and again in 1854 with the arrival of the railway to Brantford.

Because of the ease of navigation from new roads and the Grand River, several manufacturing companies could be found in the town by 1869.[18] Some of these factories included Brantford Engine Works, Victoria Foundry and Britannia Foundry.[18] Several major farm implement manufacturers, starting with Cockshutt and Harris, opened for business in the 1870s.

The history of the Brantford region from 1793 to 1920 is described at length in the book At The Forks of The Grand.[19]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, both the United States and Canadian governments encouraged education of First Nations children at residential schools, which were intended to teach them English and European-American ways and assimilate them to the majority cultures. These institutions in Western New York and Canada included the Thomas Indian School, Mohawk Institute Residential School (also known as Mohawk Manual Labour School and Mush Hole Indian Residential School) in Brantford, Southern Ontario, Haudenosaunee boarding school, and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Decades later and particularly since the late 20th century, numerous scholarly and artistic works have explored the detrimental effects of the schools in destroying Native cultures. Examples include: the film Unseen Tears: A Documentary on Boarding School Survivors,[20] Ronald James Douglas' graduate thesis titled Documenting Ethnic Cleansing in North America: Creating Unseen Tears,[21] and the Legacy of Hope Foundation's online media collection: "Where are the Children? Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools".[22]

In June 1945, Brantford became the first city in Canada to fluoridate its water supply.[23][24]

Brantford generated controversy in 2010 when its city council expropriated and demolished 41 historic downtown buildings on the south side of its main street, Colborne Street. The buildings constituted one of the longest blocks of pre-Confederation architecture in Canada, and included one of Ontario's first grocery stores and an early 1890s office of the Bell Telephone Company of Canada. The decision was widely criticized by Ontario's heritage preservation community, however the city argued it was needed for downtown renewal.[25][26]

Historical plaques and memorials

Plaques and monuments erected by the provincial and federal governments provide additional glimpses into the early history of the area around Brantford.[27]

The famed Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant (Thayendanega) led his people from the Mohawk Valley of New York State to Upper Canada after being allied with the British during the American Revolution where they lost their land holdings. A group of 400 settled in 1788 on the Grand River at Mohawk Village which would later become Brantford.[27] Nearly a century later (1886), the Joseph Brant Memorial would be erected in Burlington, Ontario in honour of Brant and the Six Nations Confederacy.[28]

The Mohawk Chapel, built by the British Crown in 1785 for the Mohawk and Iroquois people (Six Nations of the Grand River) was dedicated in 1788 as a reminder of the original agreements made with the British during the American Revolution.[27] In 1904 the chapel received Royal status by King Edward VII in memory of the longstanding alliance. Her Majesty's Royal Chapel of the Mohawks is an important reminder of the original agreements made with Queen Anne in 1710. It is still in use today as one of two royal Chapels in Canada and the oldest Protestant Church in the province. Joseph Brant and his son John Brant are buried here.[29]

Chief John Brant (Mohawk leader) (Ahyonwaeghs) was one of the sons of Joseph Brant.[30] He fought with the British during the War of 1812 and later worked to improve the welfare of the First Nations. He was involved in building schools and improving the welfare of his people. Brant initiated the opening of schools and from 1828 served as the first native Superintendent of the Six Nations.[27] Chief Brant was elected to Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada for Haldimand in 1830 and was the first aboriginal Canadian in Parliament.[31]

The stone and brick Brant County Courthouse was built on land purchased from the Six Nations in 1852. The structure housed court rooms, county offices, a law library and a gaol. During additions in the 1880s, the Greek Revival style, with Doric columns, was retained.[27]

Among the most famed residents were Alexander Graham Bell and his family, who arrived in mid 1870 from Scotland while Bell was suffering from tuberculosis. They lived with Bell's father and mother who had settled in a farmhouse on Tutela Heights (named after the First Nations tribe of the area[32] and later absorbed into Brantford.) Then called Melville House, it is now a museum, the Bell Homestead National Historic Site. This was the site of the invention of the telephone in 1874 and ongoing trials in 1876. The Bell Memorial, also known as the Bell Monument, was commissioned to commemorate Bell's invention of the telephone in Brantford; it is also one of the National Historic Sites of Canada.

Invention of the telephone

Some articles suggest that the telephone was invented in Boston where Alexander Graham Bell did a great deal of work on the development of the device.[33] However, Bell confirmed Brantford as the birthplace of the device in a 1906 speech: "the telephone problem was solved, and it was solved at my father's home".[34] At the unveiling of the Bell Memorial on 24 October 1917, Bell reminded the attendees that "Brantford is right in claiming the invention of the telephone here... [which was] conceived in Brantford in 1874 and born in Boston in 1875" and that "the first transmission to a distance was made between Brantford and Paris" (on 3 August 1876).[35][36] As well, the second successful voice transmission (over a distance of 6 km; 4 miles) was also made in the area, on 4 August 1876, between the telegraph office in Brantford, Ontario and Bell's father's homestead over makeshift wires.[37][38]

Canada's first telephone factory, created by James Cowherd, was located in Brantford and operated from about 1879 until Cowherd's death in 1881.[39][40] The first telephone business office which opened in 1877, not far from the Bell Homestead, was located in what is now Brantford.[27] The combination of events has led to Brantford calling itself "The Telephone City".

Law and Government

Brantford is located within the County of Brant; however, it is a single-tier municipality, politically separate from the County.[4][5][6] Ontario's Municipal Act, 2001 defines single-tier municipalities as "a municipality, other than an upper-tier municipality, that does not form part of an upper-tier municipality for municipal purposes".[41] Single-tier municipalities provide for all local government services.[42]

At the federal and provincial levels of government, Brantford is part of the Brant riding.

Brantford City Council is the municipal governing body. As of October 22, 2018, the mayor is Kevin Davis.

Safety

Brantford's economy was hit hard in the 1980s when farm equipment manufacturers Massey Ferguson and White Farm Equipment closed their local plants.[43] By the end of 1981, the city's unemployment rate reached 22%.[43] As with other small Ontario cities hit by the decline of manufacturing, the community struggled with an increase in social problems.[43]

In more recent times, the city was hit hard by the opioid crisis. In 2018, Brantford had the highest rate of emergency department visits for overdose of any city in Ontario.[44][45] In 2018, Brantford police reported an overall crime rate of 6,533 incidents per 100,000 population, 59% higher than in Ontario (4,113) and 19% higher than in Canada (5,488).[46] The same year, Maclean's magazine ranked Brantford as having a higher rate of crime severity than most of the province.[47]

Economy

The electric telephone was invented here, leading to the establishment of Canada's first telephone factory here in the 1870s. Brantford developed as an important Canadian industrial centre for the first half of the 20th century, and it was once the third-ranked Canadian city in terms of cash-value of manufactured goods exported.

The city developed at the deepest navigable point of the Grand River. Because of existing networks, it became a railroad hub of Southern Ontario. The combination of water and rail helped Brantford develop from a farming community into an industrial city with many blue-collar jobs, based on the agriculture implement industry. Major companies included S.C. Johnson Wax, Massey-Harris, Verity Plow, and the Cockshutt Plow Company. This industry, more than any other, provided the well-paying and steady employment that allowed Brantford to sustain economic growth through most of the 20th century.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the economy of Brantford was in steady decline due to changes in heavy industry and its restructuring. Numerous companies suffered bankruptcies, such as White Farm Equipment, Massey Ferguson (and its successor, Massey Combines Corporation), Koering-Waterous, Harding Carpets, and other manufacturers. The bankruptcies and closures of the businesses left thousands of people unemployed and created one of the most economically depressed areas in the country, and had a particular impact on the once vibrant downtown.

An economic revival was prompted by the completion of the Brantford-to-Ancaster section of Highway 403 in 1997, bringing companies easy access to Hamilton and Toronto and completing a direct route from Detroit to Buffalo. In 2004 Procter & Gamble and Ferrero SpA chose to locate in the city. Though Wescast Industries, Inc. recently closed their local foundry, their corporate headquarters will remain in Brantford. SC Johnson Canada has their headquarters and a manufacturing plant in Brantford, connected to the Canadian National network. Other companies that have their headquarters here include Gunther Mele and GreenMantra Technologies. On February 16, 2005, Brant, including Brantford, was added to the Greater Golden Horseshoe along with Haldimand and Northumberland counties.

In February 2019, Brantford's unemployment rate stood at 4.6% – lower than Ontario's rate of 5.6%.[48]

Climate

Brantford has a humid continental climate (Dfb) with warm to hot summers and cold, moderately snowy winters, though not severe by Canadian standards.

| Climate data for Brantford (1981−2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

25.5 (77.9) |

30.5 (86.9) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.5 (95.9) |

38.5 (101.3) |

36.5 (97.7) |

34.4 (93.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

38.5 (101.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

0.3 (32.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

19.3 (66.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

7.9 (46.2) |

1.4 (34.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6 (21) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

0.3 (32.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

13.5 (56.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

9.3 (48.7) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −10.4 (13.3) |

−8.9 (16.0) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.4 (59.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

3.0 (37.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30 (−22) |

−30.5 (−22.9) |

−24 (−11) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−3 (27) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−7 (19) |

−16 (3) |

−27 (−17) |

−30.5 (−22.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 54.7 (2.15) |

51.5 (2.03) |

59.1 (2.33) |

68.9 (2.71) |

81.1 (3.19) |

75.9 (2.99) |

95.0 (3.74) |

75.0 (2.95) |

86.6 (3.41) |

70.1 (2.76) |

84.4 (3.32) |

65.1 (2.56) |

867.3 (34.15) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 27.6 (1.09) |

30.4 (1.20) |

43.5 (1.71) |

65.3 (2.57) |

81.1 (3.19) |

75.9 (2.99) |

95.0 (3.74) |

75.0 (2.95) |

86.6 (3.41) |

70.1 (2.76) |

78.3 (3.08) |

40.8 (1.61) |

769.6 (30.30) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 27.1 (10.7) |

21.9 (8.6) |

15.6 (6.1) |

3.6 (1.4) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

6.1 (2.4) |

24.2 (9.5) |

98.4 (38.7) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 11.3 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 12.2 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 13.2 | 12.0 | 135.6 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 4.5 | 4.7 | 8.1 | 11.6 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 12.2 | 11.8 | 7.0 | 114.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 7.0 | 5.4 | 3.7 | 0.92 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 5.8 | 24.4 |

| Source: Environment Canada[49] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Brantford had a population of 104,688 living in 41,673 of its 43,269 total private dwellings, a change of 6.2% from its 2016 population of 98,563. With a land area of 98.65 km2 (38.09 sq mi), it had a population density of 1,061.2/km2 (2,748.5/sq mi) in 2021.[50]

At the census metropolitan area (CMA) level in the 2021 census, the Brantford CMA had a population of 144,162 living in 56,003 of its 58,047 total private dwellings, a change of 7.4% from its 2016 population of 134,203. With a land area of 1,074 km2 (415 sq mi), it had a population density of 134.2/km2 (347.7/sq mi) in 2021.[51]

95,780 gave their ethnic background on the 2016 census.[52] Brantford has the highest proportion of Status Indians in Southern Ontario, outside of an Indian reserve.[53]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1841 | 2,000 | — |

| 1871 | 8,107 | +305.3% |

| 1881 | 9,616 | +18.6% |

| 1891 | 12,753 | +32.6% |

| 1901 | 16,619 | +30.3% |

| 1911 | 23,132 | +39.2% |

| 1921 | 29,440 | +27.3% |

| 1931 | 30,107 | +2.3% |

| 1941 | 31,622 | +5.0% |

| 1951 | 36,727 | +16.1% |

| 1961 | 55,201 | +50.3% |

| 1971 | 64,421 | +16.7% |

| 1981 | 74,315 | +15.4% |

| 1991 | 81,997 | +10.3% |

| 1996 | 84,764 | +3.4% |

| 2001 | 86,417 | +2.0% |

| 2006 | 90,192 | +4.4% |

| 2011 | 93,650 | +3.8% |

| 2016 | 98,563 | +5.2% |

| 2021 | 104,688 | +6.2% |

| [54] | ||

| Population group | Population | % of total population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible minority group Source:[55] |

South Asian | 3,115 | 3.3% |

| Chinese | 785 | 0.8% | |

| Black | 2,015 | 2.1% | |

| Filipino | 750 | 0.8% | |

| Latin American | 445 | 0.5% | |

| Arab | 435 | 0.5% | |

| Southeast Asian | 1,055 | 1.1% | |

| Korean | 230 | 0.2% | |

| Other visible minority | 295 | 0.3% | |

| Multiple visible minority | 320 | 0.3% | |

| Total visible minority population | 9,440 | 9.9% | |

| Aboriginal group Source:[55] | First Nations | 4,365 | 4.6% |

| Métis | 845 | 0.9% | |

| Inuit | 20 | 0% | |

| Other Aboriginal | 90 | 0.1% | |

| Multiple Aboriginal identity | 85 | 0.1% | |

| Total Aboriginal population | 5,225 | 5.5% | |

| European | 81,115 | 84.7% | |

| Total population in private households | 95,780 | 100% | |

Film and television

Brantford has been used as a filming location for TV and films.

- The television series Murdoch Mysteries has used the Carnegie Building, now part of Wilfrid Laurier University's Brantford campus, as the courthouse.[56] The interior of the Sanderson Centre for the Performing Arts has also been featured in the series.[56][57] In addition, Victoria Park and many of the older homes along Dalhousie and George streets have been used for shot locations.[57]

- The television series The Boys upcoming season 3 was partially filmed in Brantford during the spring of 2021.[58]

- The television series The Handmaid's Tale had several locations filmed in Brantford during 2018,2020 and 2022.[59]

- Several movies have had scenes shot at the Brantford Airport, including Welcome to Mooseport and Where the Truth Lies. Many Mayday episodes have also been filmed there.[citation needed]

- An episode of Due South, "Dr. Long Ball", was filmed at Arnold Anderson Stadium in Cockshutt Park.

- Brantford's downtown provided locations for Weirdsville in 2006 and "Silent Hill" in 2005. Many area residents[60] observed that little work had to be done to make downtown look decayed and haunted.

- Brantford's Sanderson Centre for the Performing Arts was used as "The Rose" mainstage theatre of the "New Burbage Festival" in the series Slings & Arrows.[citation needed]

Education

Statistics from the Federal 2016 Census indicated that 54.1% of Brantford's adult residents (age 25 to 64) had earned either a Post-secondary certificate, diploma, or university degree.

Universities and colleges

Several post-secondary institutions have facilities in Brantford.

- Laurier Brantford, a campus of Wilfrid Laurier University, offers a variety of programs at their downtown campus.[61] The 2013-14 enrollment is 2,800 full-time students.

- The Faculty of Liberal Arts includes Contemporary Studies, Journalism, History, English, Youth and Children's Studies, Human Rights and Human Diversity, Languages at Brantford and Law and Society programs. The Faculty of Human and Social Sciences includes Criminology, Health Studies, Psychology and Leadership.

- The Faculty of Social Work includes the Bachelor of Social Work.

- The Faculty of Graduate and Post-Doctoral Studies includes Social Justice and Community Engagement (MA) and Criminology (MA)

- The School of Business and Economics includes Business Technology Management.

- Six Nations Polytechnic operates out of the former Mohawk College campus.[62] The school offers various 2-year college programs from their campus in Brantford. They also have a campus on the nearby Six Nations of the Grand River, catering to mostly university programs.[63]

- Nipissing University, in partnership with Laurier Brantford, offers the Concurrent Education program in Brantford. In five years, students earn an Honours Bachelor of Arts in Society, Culture & Environment from Laurier Brantford, and a Bachelor of Education from Nipissing University.[64] During the 2013–14 academic year there were 70 full-time and 100 part-time students in the program.

- Conestoga College offers academic programming in Brantford's downtown core in partnership with Wilfrid Laurier University and its Laurier Brantford campus. Conestoga College offer diplomas in Business and Health Office Administration, a graduate certificate in Human Resources Management, and a certificate in Medical Office Practice in Brantford.[65] This program has 120 full-time students in the 2013–14 academic year.

- Mohawk College had a satellite campus; however, the college ceased operations in Brantford and transferred the property to Six Nations Polytechnic at the end of the 2013–14 academic year.[66]

Secondary schools

Public education in the area is managed by the Grand Erie District School Board, and Catholic education is managed by the Brant Haldimand Norfolk Catholic District School Board.

- Assumption College School (Catholic)

- Brantford Collegiate Institute - successor to Brantford Grammar School (c. 1852) and Brantford High School (c. 1871).

- North Park Collegiate & Vocational School

- Pauline Johnson Collegiate & Vocational School

- St. John's College (Catholic)

- Tollgate Technological Skills Centre (formerly known as Herman E. Fawcett)

- Grand Erie Learning Alternatives (GELA)

Elementary schools

Public education in the area is managed by the Grand Erie District School Board, and Catholic education is managed by the Brant Haldimand Norfolk Catholic District School Board and the Conseil Scolaire de District Catholique Centre-Sud.

- Christ The King School (Catholic)[67]

- St. Peter School (Catholic)

- Holy Cross School (Catholic)

- St. Basil Catholic Elementary School (Catholic)

- Jean Vanier Catholic Elementary School (Catholic)

- Notre Dame Catholic Elementary School (Catholic)

- St. Pius X Catholic Elementary School (Catholic)

- St. Gabriel Catholic Elementary School (Catholic)

- Our Lady of Providence Catholic Elementary School (Catholic)

- Resurrection School (Catholic)

- St. Leo School (Catholic)

- St. Patrick School (Catholic)

- Russell Reid Elementary School[68]

- Woodman-Cainsville School

- Echo Place School

- Cedarland Public School

- Centennial-Grand Woodlands School

- École Confederation (French Immersion)

- Dufferin Public School (French Immersion)

- Walter Gretzky Elementary School

- Mount Pleasant Public School

- Ryerson Heights Elementary School

- Graham Bell-Victoria Public School

- Lansdowne-Costain Public School

- Major Ballachey Public School

- Agnes G. Hodge Public School

- Prince Charles Public School

- Greenbrier Public School

- James Hillier Public School

- Grandview Public School

- Banbury Heights School

- King George School

- Branlyn School

- Brier Park School

- Central School

- Princess Elizabeth Public School

- Bellview Public School

- St. Marguerite Bourgeois (French)

- Brantford Christian School (Separate)

- Central Baptist Academy (Baptist)

Other

- The W. Ross Macdonald School for blind and deafblind students is located in Brantford.

- The Mohawk Institute Residential School, a Canadian Indian residential school, was located in Brantford. It was closed after emphasis on educating children in their home communities and encouraging their own cultures, in part because of reporting of abuses at such facilities.

- Victoria Academy is a private secondary school in Brantford.

- Braemar House School is a private elementary school in Brantford offering diverse Montessori and Elementary School curriculum.

Media

The Brantford Expositor, started in 1852, is published six days per week (excluding Sundays) by Sun Media Corp.

The Brant News was a weekly paper, delivered Thursdays until 2018; it publishes breaking news online at their website,[69] and is published by Metroland Media Group.

The Two Row Times, a Free weekly paper started in 2013, is published on Wednesdays, delivered to every reservation in Ontario and globally online at their website,[70] published by Garlow Media.

BScene, a Free community paper founded in 2014, is published monthly and distributed locally throughout Brantford and Brant County via local businesses and community centers, It can also be viewed online at their website.[71] Independently published.

Radio

- AM 1380 - CKPC (AM), religious

- FM 92.1 - CKPC-FM, adult contemporary

- FM 93.9 - CFWC-FM, country music

Television

Brantford's only local television service comes from Rogers TV (cable 20), a local community channel on Rogers Cable. Otherwise, Brantford is served by stations from Toronto, Hamilton and Kitchener.

Transportation

Air

Brantford Municipal Airport is located west of the city. It hosts an annual air show, featuring the Snowbirds. The John C. Munro Hamilton International Airport in Hamilton is located about 35 km (20 miles) east of Brantford. Toronto Pearson International Airport is located in Mississauga, about 100 km (60 miles) northeast of Brantford.

Rail

Brantford station is located just north of downtown Brantford. Via Rail has daily passenger trains on the Quebec City-Windsor Corridor. Trains also stop at Union Station in Toronto.

Street rail began in Brantford in 1886 with horse-drawn carriages; by 1893 this system had been converted to electric. The City of Brantford took over these operations in 1914. Around 1936 it began to replace the electric street car system with gas-run buses, and by the end of 1939 the change-over was complete.[72]

Bus

- Brantford Transit serves the city with nine regular routes operating on a half-hour schedule from the downtown Transit Terminal on Darling Street, with additional school service.

- GO bus service between downtown Brantford and Aldershot GO Station in Burlington, stopping at McMaster University.

- An on-demand service, Brant eRide, provides service to Paris, St. George, and Burford.

Provincial highways

- Highway 403, East to Hamilton, West to Woodstock.

- Highway 24, North to Cambridge, South to Simcoe.

Cycling

As of 2022[update], there are at least 18 km (11 mi) of bikeways in Brantford.[73] There are some planned street redesigns which include protected bike lanes and multi-use trails, which as of 2022[update] are in the public consultation phase.[74]

Some former rail lines serving Brantford have been converted to rail trails, which allow for intercommunity cycling connections to the north, south, and east. This includes the SC Johnson Trail to Paris (with further connections north to Cambridge and beyond)[75] and the Hamilton to Brantford Rail Trail, which provides a connection east to Hamilton through Dundas and Jerseyville.[76] Twin rail trails, the LE&N Trail and TH&B Trail, connect south to Mount Pleasant, where they connect further south ultimately to Port Dover.[77]

Culture and entertainment

Local museums include the Bell Homestead, Woodland Cultural Centre,[78] Brant Museum and Archives,[79] Canadian Military Heritage Museum[80] and the Personal Computer Museum.

Annual events include the "Brantford International Villages Festival" in July;[81] the "Brantford Kinsmen Annual Ribfest" in August;[82] the "Chili Willy Cook-Off" in February; the "Frosty Fest", a Church festival held in winter;[83]

The Bell Summer Theatre Festival,[84] takes place from Canada Day to Labour Day at the Bell Homestead

Brantford is the home of several theatre groups including Brant Theatre Workshops,[85] Dufferin Players, His Majesty's players, ICHTHYS Theatre, Stage 88, Theatre Brantford and Whimsical Players.

Brantford has a casino, Elements Casino Brantford. The Sanderson Centre for the Performing Arts is a local performance venue.[86]

Brantford Public Library

Brantford Public Library's central branch is located downtown on Colborne Street. It has an additional branch on St. Paul Avenue.[87] It has been automated since 1984.[88] In 2000, the library was the first in North America to join the UNESCO model library network.[88]

Sports teams and tournaments

Current intercounty or major teams

- Brantford Red Sox of the Intercounty Baseball League who play at Arnold Anderson Stadium

- Brantford Braves of the Junior Intercounty Baseball League who also play at Arnold Anderson Stadium

- Brantford Blast of the Allan Cup Hockey League who play at the Brantford Civic Centre

- Brantford 99ers of the Ontario Junior Hockey League

- Brantford Bandits of the Greater Ontario Junior Hockey League

- Brantford Galaxy SC of the Canadian Soccer League who play at Lion's Park.

- Brantford Harlequins of the Ontario Rugby Union

Defunct teams

- Brantford Alexanders (1976 to 1978), a former team of the Senior Ontario Hockey Association who played at the Brantford Civic Centre. Won 1978 Allan Cup.

- Brantford Motts Clamatos. Won 1987 Allan Cup.

- Brantford Golden Eagles of the Greater Ontario Junior Hockey League, moved in 2012 to become Caledonia Corvairs.

- Brantford Alexanders (1978 to 1984), a former team of the Ontario Hockey League who played at the Brantford Civic Centre. They are now the Erie Otters.

- Brantford Smoke (1991–1998) of the CoHL, Colonial Hockey League who played at the Brantford Civic Centre. The team moved to Asheville in 1998.

- Brantford Blaze of the Canadian National Basketball League, played only a few exhibition games in 2003–04.

Events

- The Wayne Gretzky International Hockey Tournament,[89] which celebrated its 9th anniversary in 2015,[90] is held in Brantford annually

- Brantford hosted and won the 2008 Allan Cup, which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the event.[91]

- The city served as the pre-season camp and facility for the Pittsburgh Penguins during the late 1960s, hosting the franchise's first preseason training camp and its first preseason exhibition game.[92]

- The Walter Gretzky Street Hockey Tournament, celebrated its 10th anniversary in 2016, is held in Brantford annually. In 2010, this "great" tournament was recognized and established a Guinness World Record for the largest Street Hockey Tournament in the world with 205 teams with just over 2,096 participants.

Notable people

Twin towns – sister cities

Brantford is twinned with:

Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland[93]

Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland[93] Kamianets-Podilskyi, Ukraine[94]

Kamianets-Podilskyi, Ukraine[94]

See also

- Alexander Graham Bell

- Brant (electoral district)

- Brantford City Council

- List of mayors of Brantford, Ontario

References

- "Brantford Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- "Brantford Ontario [Census metropolitan area] Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- "Table 36-10-0468-01 Gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, by census metropolitan area (CMA) (x 1,000,000)". Statistics Canada. 27 January 2017. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- "Proposed Boundary Adjustment". Brant.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-04-07. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- "Members of Council". Brantford.ca. 2019-03-21. Archived from the original on 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- "Councillors and Wards - County of Brant". Brant.ca. Archived from the original on 2018-04-02. Retrieved 2018-12-31.

- "Haldimand Tract". Grand River Country. Archived from the original on 2019-07-09. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- Filice, Michelle (December 16, 2020). "Haldimand Proclamation". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- Francis, Daniel (December 16, 2020). "Brantford". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- Shanahan, David (December 7, 2019). "Between the Lakes Treaty". Anishinabek News. Archived from the original on June 5, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- "Sophia Burthen Pooley: Part of the Family?". Ontario Ministry of Government and Consumer Services. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2021.

- Reville, F. Douglas. The History of the County of Brant Archived 2010-02-15 at the Wayback Machine, Brantford: Hurley Printing Company, vol. 1, pp. 15–20, 1920.

- "Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea) | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Archived from the original on 2021-06-05. Retrieved 2021-06-05.

- "- Grand River Branch - United Empire Loyalists' Association of Canada". www.grandriveruel.ca. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- "Lieuxpatrimoniaux.ca - HistoricPlaces.ca". www.historicplaces.ca. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Smith, Wm. H. (1846). SMITH'S CANADIAN GAZETTEER - STATISTICAL AND GENERAL INFORMATION RESPECTING ALL PARTS OF THE UPPER PROVINCE, OR CANADA WEST. Toronto: H. & W. ROWSELL. p. 19.

- "Brantford Facts". Brantford.ca. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Henry McEvoy (21 October 1869). The Province of Ontario Gazetteer and Directory: Containing Concise ... Robertson & Cook. ISBN 9780665094125. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- Smith, Donald Alexander; (Ont.), Paris Public Library Board (21 October 2017). At the Forks of the Grand. Brant County Library. ISBN 9780969124511. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- ICTMN Staff (December 2, 2010). "Unseen Tears: A Documentary on Boarding School Survivors". Indian Country Today Media Network. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- Douglas, Ronald James (2010). "Documenting ethnic cleansing in North America: Creating unseen tears (AAT 1482210)". ProQuest 757916758.

- Legacy of Hope Foundation. "Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools". Where Are the Children?. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- Chris Purdy (March 10, 2016). "The great debate to fluoridate (or not)". Hamilton Spectator. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Madeline Smith; Andrew Jeffery (January 14, 2019). "Windsor, Ont. flips back to fluoride — why that's unlikely to change minds in Calgary". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Blaze Carlson, Katherine (June 8, 2010). "Ontario city to demolish historic street, despite Ottawa's objection". Toronto Sun. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- Wilkes, Jim (June 8, 2010). "Demolition of historic buildings begins in Brantford". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- "Historical Plaques of Brant County". Waynecook.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-26. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- "Thayendanega (Joseph Brant) Historical Plaque". ontarioplaques.com. Archived from the original on 2021-08-21. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- "History". Mohawk Chapel. 2011. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- "War of 1812". Eighteentwelve.ca. Archived from the original on 2018-10-13. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- "Ahyouwaighs, Chief of the Six Nations 1838". vitacollections.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-04-08. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- Patten, William; Bell, Alexander Melville. Pioneering The Telephone In Canada Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine, Montreal: Herald Press, 1926, pg.7. (Note: Patten's full name as published is William Patten, not Gulielmus Patten as stated at Google Books)

- Haughton, Robert N. E. "Alexander Graham Bell and the Invention of the Telephone". Telecommunications.ca. The Telecommunications Mosaic: An Introduction to the Information Age. Archived from the original on 2016-07-25. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- Reville, F. Douglas (1920). History of the County of Brant (PDF). Brantford, Ontario: Hurley. p. 315. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "The Unveiling of the Bell Memorial" (PDF). Brantford.library.on.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- Reville, F. Douglas. History of the County of Brant Vol. 1. Brantford, ON: Brant Historical Society, Hurley Printing, 1920/. PDF pp. 187–197, or document pp. 308–322. (PDF)

- "Alexander Graham Bell & Brantford". Brantford.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-04-07. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- MacLeod, Elizabeth (1999). Alexander Graham Bell: An Inventive Life. Toronto, Ontario: Kids Can Press. p. 14 to 19. ISBN 1-55074-456-9

- "Evolution of Telecommunications". Virtualmuseum.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-03-04. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- Murray, Robert P. (21 October 2017). The Early Development of Radio in Canada, 1901-1930: An Illustrated History of Canada's Radio Pioneers, Broadcast Receiver Manufacturers, and Their Products. Sonoran Publishing. ISBN 9781886606203. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 21 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- "Law Document English View". 24 July 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "AMO - Ontario Municipalities". Amo.on.ca. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- Freeze, Jason (25 October 2018). "Brantford in the 1980's - Part 4". BScene. BScene. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- Gee, Marcus (24 February 2019). "In Brantford's opioid nightmare, a community sees more hopeful days ahead". Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- "Brantford struggles to deal with opioid crisis and homelessness". NorthbayNipissing.com. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada. "Safe Cities profile series: Key indicators by census metropolitan area - Brantford, Ontario". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- "Canada's Most Dangerous Places 2018: Explore the data". Macleans.ca. Maclean's magazine. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "CANSIM - 282-0135 - Labour force survey estimates (LFS), by census metropolitan area based on 2011 Census boundaries, 3-month moving average, seasonally adjusted and unadjusted". 5.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-05-17. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

- "Brantford MOE". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Environment Canada. 2013-09-25. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census divisions and census subdivisions (municipalities), Ontario". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

- "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved March 28, 2022.

- "Brantford (City) community profile". 2016 Census data. Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2013-02-21.

- "Census Mapper (Status Indians)". Census Mapper. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- "File Not Found". 12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics (2013-05-08). "2011 National Household Survey Profile - Census subdivision". 12.statcan.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- Ruby, Michelle (August 28, 2012). "Murdoch Mysteries filming in Brantford". The Expositor. Archived from the original on 2014-02-26. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Ruby, Michelle (October 1, 2013). "No mystery Murdoch is popular". The Expositor. Archived from the original on 2014-02-26. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Filming Notice – April 13-17, 2021". City of Brantford. April 13, 2021. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Ruby, Michelle (March 4, 2021). "Brantford has starring role in record number of film productions in 2020". Brantford Expositor. Archived from the original on June 9, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- "A Walk On The South Side" Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, Brantford Expositor, 10 June 2010

- "Wilfrid Laurier University - Laurier Brantford - Academic Information/Advising". Wlu.ca. Archived from the original on 2014-02-21.

- "Mohawk set to transfer Brantford campus to Six Nations Polytechnic". CBC News. August 31, 2013. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- "Programs & Courses". Six Nations Polytechnic. 29 November 2016. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- "Brantford Campus : Nipissing University". Nipissingu.ca. Archived from the original on 2018-04-08. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- "Brantford Campus - Conestoga College". Conestogac.on.ca. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- "Mohawk College to expand Hamilton programs for Brantford students" Archived 2014-02-25 at the Wayback Machine, Mohawk Matters

- "Schools | Brant Haldimand Norfolk Catholic District School Board". www.bhncdsb.ca. Archived from the original on 2015-09-19. Retrieved 2015-09-08.

- "Elementary Schools". www.granderie.ca. Archived from the original on 2015-09-14. Retrieved 2015-09-08.

- "Brantford-Brant News - Latest Daily Breaking News Stories - BrantNews.com". BrantNews.com. Archived from the original on 2010-07-10. Retrieved 2010-07-14.

- "Homepage". 22 December 2013. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- "BScene". BScene. Archived from the original on 2015-02-27. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- Brantford, Ontario Principal System Archived 2012-03-09 at the Wayback Machine, Canadian Street Railways. 31-Mar-2011.

- "Bike and Trail Maps". City of Brantford. 25 June 2020. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "Bike Lanes". City of Brantford. 7 March 2022. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "SC Johnson Trail". Grand River Conservation Authority. 18 February 2022. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "Brantford to Hamilton Rail Trail". Grand River Conservation Authority. 18 July 2022. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "Other trails". Grand River Conservation Authority. 17 December 2021. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "Woodland Cultural Centre". Woodland Cultural Centre. Archived from the original on 2017-08-22. Retrieved 2017-08-22.

- "Brant Historical Society". Brant Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2007-10-01. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- "The Canadian Military Museum". Archived from the original on 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- Committee, The Brantford International Villages. "International Villages Cultural Festival - (Brantford International Villages Festival) - 44th Cultural Exchange: July 5th - 8th, 2017". Brantfordvillages.ca. Archived from the original on 2012-05-30. Retrieved 2012-04-14.

- "Brantford Kinsmen Ribfest". Brantfordribfest.ca. Archived from the original on 2022-05-03. Retrieved 2015-02-20.

- "Frosty Fest celebrates winter". Brantford Expositor. Archived from the original on 2016-11-09. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- "Brant Theatre Workshops :: Bell Summer Festival". branttheatre.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-16. Retrieved 2017-03-15.

- "Brant Theatre Workshops :: Home". branttheatre.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-17. Retrieved 2017-03-15.

- SandersonCentre. "Home". Sandersoncentre.ca. Archived from the original on 2013-10-22. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- "Contact us". Brantford Public Library. Archived from the original on 2012-06-25. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- Kirk, Denise (2000). "History of the Brantford Public Library". Brantford Public Library. Archived from the original on July 27, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- "2016-2017 > Wayne Gretzky International Hockey Tournament (Brantford Minor Hockey Association)". brantfordminorhockey.com. Archived from the original on 2016-11-10. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- Gamble, Susan (21 June 2015). "Walter Gretzky Street Hockey Tournament: Look for 'big things' for 10th anniversary". Brantford Expositor. Archived from the original on 2016-06-02. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- "Brantford Blast 2008 Allan Cup Champions". Allan Cup 2008. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- "Pittsburgh Penguins Start With Many Goalies On Team". Observer-Reporter. 13 September 1967. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- Ball, Vincent (30 May 2009). "City gets a twin". Brantford Expositor. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-24.

- "Brantford signs twinning agreement with Ukrainian city". Kitchener. 2022-04-04. Archived from the original on 2022-04-27. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

External links

На других языках

[de] Brantford

Brantford [.mw-parser-output .IPA a{text-decoration:none}ˈbɹænfərd] ist eine Stadt in der kanadischen Provinz Ontario. Sie wird von der Gemeinde County of Brant umschlossen.- [en] Brantford

[ru] Брантфорд

Бра́нтфорд (англ. Brantford) — город, расположенный на реке Гранд-Ривер на юго-западе провинции Онтарио, Канада[1]. По результатам переписи населения, на 2011 год население города составляло 94 000 человек, а с пригородами около 135 500.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии