world.wikisort.org - USA

Portland (/ˈpɔːrtlənd/, PORT-lənd) is a port city in the Pacific Northwest and the largest city in the U.S. state of Oregon. Situated at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers, Portland is the county seat of Multnomah County, the largest county in Oregon by population. As of 2020, Portland had a population of 652,503,[9] making it the 26th-most populated city in the United States, the sixth-most populous on the West Coast, and the second-most populous in the Pacific Northwest, after Seattle.[10] Approximately 2.5 million people live in the Portland metropolitan statistical area (MSA), making it the 25th most populous in the United States. About half of Oregon's population resides within the Portland metropolitan area.[lower-alpha 1]

Portland, Oregon | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Portland | |

From top: The city and Mount Hood from Pittock Mansion, St. Johns Bridge, Oregon Convention Center, Union Station and U.S. Bancorp Tower, Pioneer Courthouse Square, Tilikum Crossing | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): "Rose City"; "Stumptown"; "PDX"; see Nicknames of Portland, Oregon for a complete list. | |

Interactive map of Portland | |

| Coordinates: 45°31′12″N 122°40′55″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Counties | Multnomah Washington Clackamas |

| Founded | 1845 |

| Incorporated | February 8, 1851 |

| Named for | Portland, Maine[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Commission |

| • Mayor | Ted Wheeler[2] (D) |

| • Commissioners |

|

| • Auditor | Mary Hull Caballero |

| Area | |

| • City | 145.00 sq mi (375.55 km2) |

| • Land | 133.49 sq mi (345.73 km2) |

| • Water | 11.51 sq mi (29.82 km2) |

| • Urban | 524.38 sq mi (1,358.1 km2) |

| Elevation | 50 ft (15.2 m) |

| Highest elevation | 1,188 ft (362 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 0.62 ft (0.19 m) |

| Population (2020)[6] | |

| • City | 652,503 |

| • Rank | 26th in the United States 1st in Oregon |

| • Density | 4,888.10/sq mi (1,887.30/km2) |

| • Metro | 2,511,612 (25th) |

| Demonym | Portlander |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 97086–97299 |

| Area codes | 503 and 971 |

| FIPS code | 41-59000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1136645[8] |

| Website | portland.gov |

Named after Portland, Maine,[11] the Oregon settlement began to be populated in the 1840s, near the end of the Oregon Trail. Its water access provided convenient transportation of goods, and the timber industry was a major force in the city's early economy. At the turn of the 20th century, the city had a reputation as one of the most dangerous port cities in the world, a hub for organized crime and racketeering. After the city's economy experienced an industrial boom during World War II, its hard-edged reputation began to dissipate. Beginning in the 1960s,[12] Portland became noted for its growing progressive political values, earning it a reputation as a bastion of counter-culture.[13]

The city operates with a commission-based government, guided by a mayor and four commissioners, as well as Metro, the only directly elected metropolitan planning organization in the United States.[14][15] Its climate is marked by warm, dry summers and cool, rainy winters. This climate is ideal for growing roses, and Portland has been called the "City of Roses" for over a century.[16]

History

Pre-history

During the prehistoric period, the land that would become Portland was flooded after the collapse of glacial dams from Lake Missoula, in what would later become Montana. These massive floods occurred during the last ice age and filled the Willamette Valley with 300 to 400 feet (91 to 122 m) of water.[17]

Before American settlers began arriving in the 1800s, the land was inhabited for many centuries by two bands of indigenous Chinook people – the Multnomah and the Clackamas.[18] The Chinook people occupying the land were first documented in 1805 by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.[19] Before its European settlement, the Portland Basin of the lower Columbia River and Willamette River valleys had been one of the most densely populated regions on the Pacific Coast.[19]

Establishment

Large numbers of pioneer settlers began arriving in the Willamette Valley in the 1840s via the Oregon Trail, with many arriving in nearby Oregon City.[20] A new settlement then emerged ten miles from the mouth of the Willamette River,[21] roughly halfway between Oregon City and Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Vancouver. This community was initially referred to as "Stumptown" and "The Clearing" because of the many trees cut down to allow for its growth.[22] In 1843 William Overton saw potential in the new settlement but lacked the funds to file an official land claim. For 25 cents, Overton agreed to share half of the 640-acre (2.6 km2) site with Asa Lovejoy of Boston.[23]

In 1845, Overton sold his remaining half of the claim to Francis W. Pettygrove of Portland, Maine. Both Pettygrove and Lovejoy wished to rename "The Clearing" after their respective hometowns (Lovejoy's being Boston, and Pettygrove's, Portland). This controversy was settled with a coin toss that Pettygrove won in a series of two out of three tosses, thereby providing Portland with its namesake.[1] The coin used for this decision, now known as the Portland Penny, is on display in the headquarters of the Oregon Historical Society. At the time of its incorporation on February 8, 1851, Portland had over 800 inhabitants,[24] a steam sawmill, a log cabin hotel, and a newspaper, the Weekly Oregonian. A major fire swept through downtown in August 1873, destroying twenty blocks on the west side of the Willamette along Yamhill and Morrison Streets, and causing $1.3 million in damage,[25] roughly equivalent to $29.4 million today.[26] By 1879, the population had grown to 17,500 and by 1890 it had grown to 46,385.[27] In 1888, the first steel bridge on the West Coast was opened in Portland,[28] the predecessor of the 1912 namesake Steel Bridge that survives today. In 1889, Henry Pittock's wife, Georgiana, established the Portland Rose Society. The movement to make Portland a "Rose City" started as the city was preparing for the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition.[16]

Portland's access to the Pacific Ocean via the Willamette and Columbia rivers, as well as its easy access to the agricultural Tualatin Valley via the "Great Plank Road" (the route of current-day U.S. Route 26), provided the pioneer city with an advantage over other nearby ports, and it grew very quickly.[29] Portland remained the major port in the Pacific Northwest for much of the 19th century, until the 1890s, when Seattle's deepwater harbor was connected to the rest of the mainland by rail, affording an inland route without the treacherous navigation of the Columbia River. The city had its own Japantown,[30] for one, and the lumber industry also became a prominent economic presence, due to the area's large population of Douglas fir, western hemlock, red cedar, and big leaf maple trees.[19]

![The White Eagle Saloon (c. 1910), one of many in Portland that had reputed ties to illegal activities such as gambling rackets and prostitution[31]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e6/White_Eagle_Portland.jpg/200px-White_Eagle_Portland.jpg)

Portland developed a reputation early in its history as a hard-edged and gritty port town.[32] Some historians have described the city's early establishment as being a "scion of New England; an ends-of-the-earth home for the exiled spawn of the eastern established elite."[33] In 1889, The Oregonian called Portland "the most filthy city in the Northern States", due to the unsanitary sewers and gutters,[34] and, at the turn of the 20th century, it was considered one of the most dangerous port cities in the world.[35] The city housed a large number of saloons, bordellos, gambling dens, and boardinghouses which were populated with miners after the California Gold Rush, as well as the multitude of sailors passing through the port.[32] By the early 20th century, the city had lost its reputation as a "sober frontier city" and garnered a reputation for being violent and dangerous.[32][36]

20th-century development

Between 1900 and 1930, the city's population tripled from nearly 100,000 to 301,815.[37] During World War II, it housed an "assembly center" from which up to 3,676 people of Japanese descent were dispatched to internment camps in the heartland. It was the first American city to have residents report thus,[38] and the Pacific International Livestock Exposition operated from May through September 10, 1942, processing people from the city, northern Oregon, and central Washington.[39] General John DeWitt called the city the first "Jap-free city on the West Coast."[38]

At the same time, Portland became a notorious hub for underground criminal activity and organized crime in the 1940s and 1950s.[40] In 1957, Life magazine published an article detailing the city's history of government corruption and crime, specifically its gambling rackets and illegal nightclubs.[40] The article, which focused on crime boss Jim Elkins, became the basis of a fictionalized film titled Portland Exposé (1957). In spite of the city's seedier undercurrent of criminal activity, Portland enjoyed an economic and industrial surge during World War II. Ship builder Henry J. Kaiser had been awarded contracts to build Liberty ships and aircraft carrier escorts, and chose sites in Portland and Vancouver, Washington, for work yards.[41] During this time, Portland's population rose by over 150,000, largely attributed to recruited laborers.[41]

During the 1960s, an influx of hippie subculture began to take root in the city in the wake of San Francisco's burgeoning countercultural scene.[12] The city's Crystal Ballroom became a hub for the city's psychedelic culture, while food cooperatives and listener-funded media and radio stations were established.[42] A large social activist presence evolved during this time as well, specifically concerning Native American rights, environmentalist causes, and gay rights.[42] By the 1970s, Portland had well established itself as a progressive city, and experienced an economic boom for the majority of the decade; however, the slowing of the housing market in 1979 caused demand for the city and state timber industries to drop significantly.[43]

1990s to present

In the 1990s, the technology industry began to emerge in Portland, specifically with the establishment of companies like Intel, which brought more than $10 billion in investments in 1995 alone.[44] After 2000, Portland experienced significant growth, with a population rise of over 90,000 between the years 2000 and 2014.[45] The city's increased presence within the cultural lexicon has established it as a popular city for young people, and it was second only to Louisville, Kentucky as one of the cities to attract and retain the highest number of college-educated people in the United States.[46] Between 2001 and 2012, Portland's gross domestic product per person grew fifty percent, more than any other city in the country.[46]

The city has acquired a diverse range of nicknames throughout its history, though it is most often called "Rose City" or "The City of Roses",[47] the latter of which has been its unofficial nickname since 1888 and its official nickname since 2003.[48] Another widely used nickname by local residents in everyday speech is "PDX", which is also the airport code for Portland International Airport. Other nicknames include Bridgetown,[49] Stumptown,[50] Rip City,[51] Soccer City,[52][53][54] P-Town,[48][55] Portlandia, and the more antiquated Little Beirut.[56]

2020 George Floyd protests

Starting May 28, 2020, and extending into spring 2021,[57] daily protests occurred regarding the murder of George Floyd by police and racial injustice. There were instances of looting, vandalism, and police actions causing injuries. There was the fatality of one protestor at the hands of another.[58][59][60][61] Local businesses reported losses totaling millions of dollars as the result of vandalism and looting, according to Oregon Public Broadcasting.[62] Some protests involved confrontations with law enforcement involving injury to protesters and police. In July, federal officers were deployed to safeguard federal property, whose presence and tactics were criticized by Oregon officials who demanded they leave, while lawsuits were filed against local and federal law enforcement alleging wrongful actions by them.[63][64][65][66]

On May 25, 2021, there was a protest commemorating the one-year anniversary of Floyd's murder. This protest resulted in property damage and resulted in a number of arrests.[67][68]

Geography

Geology

Portland lies on top of a dormant volcanic field known as the Boring Lava Field, named after the nearby bedroom community of Boring.[69] The Boring Lava Field has at least 32 cinder cones such as Mount Tabor,[70] and its center lies in southeast Portland. Mount St. Helens, a highly active volcano 50 miles (80 km) northeast of the city in Washington state, is easily visible on clear days and is close enough to have dusted the city with volcanic ash after its eruption on May 18, 1980.[71] The rocks of the Portland area range in age from late Eocene to more recent eras.[72]

Multiple shallow, active fault lines traverse the Portland metropolitan area.[73] Among them are the Portland Hills Fault on the city's west side,[74] and the East Bank Fault on the east side.[75] According to a 2017 survey, several of these faults were characterized as "probably more of a hazard" than the Cascadia subduction zone due to their proximities to population centers, with the potential of producing magnitude 7 earthquakes.[73] Notable earthquakes that have impacted the Portland area in recent history include the 6.8-magnitude Nisqually earthquake in 2001, and a 5.6-magnitude earthquake that struck on March 25, 1993.[76][77]

Per a 2014 report, over 7,000 locations within the Portland area are at high-risk for landslides and soil liquefaction in the event of a major earthquake, including much of the city's west side (such as Washington Park) and sections of Clackamas County.[78]

Topography

Portland is 60 miles (97 km) east of the Pacific Ocean at the northern end of Oregon's most populated region, the Willamette Valley. Downtown Portland straddles the banks of the Willamette River, which flows north through the city center and separates the city's east and west neighborhoods. Less than 10 miles (16 km) from downtown, the Willamette River flows into the Columbia River, the fourth-largest river in the United States, which divides Oregon from Washington state. Portland is approximately 100 miles (160 km) upriver from the Pacific Ocean on the Columbia.

Though much of downtown Portland is relatively flat, the foothills of the Tualatin Mountains, more commonly referred to locally as the "West Hills", pierce through the northwest and southwest reaches of the city. Council Crest Park at 1,073 feet (327 m) is often quoted as the highest point in Portland; however, the highest point in Portland is on a section of NW Skyline Blvd just north of Willamette Stone Heritage site.[79] The highest point east of the river is Mt. Tabor, an extinct volcanic cinder cone, which rises to 636 feet (194 m). Nearby Powell Butte and Rocky Butte rise to 614 feet (187 m) and 612 feet (187 m), respectively. To the west of the Tualatin Mountains lies the Oregon Coast Range, and to the east lies the actively volcanic Cascade Range. On clear days, Mt. Hood and Mt. St. Helens dominate the horizon, while Mt. Adams and Mt. Rainier can also be seen in the distance.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 145.09 square miles (375.78 km2), of which 133.43 square miles (345.58 km2) is land and 11.66 square miles (30.20 km2) is water.[80] Although almost all of Portland is within Multnomah County, small portions of the city are within Clackamas and Washington Counties, with populations estimated at 785 and 1,455, respectively.[citation needed]

Climate

Portland has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csb) falling just short of a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa) with cool and rainy winters, and warm and dry summers.[81] This climate is characterized by having overcast, wet, and changing weather conditions in fall, winter, and spring, as Portland lies in the direct path of the stormy westerly flow, and mild and dry summers when the North Pacific High reaches its northernmost point in mid-summer.[82] Portland's USDA Plant Hardiness Zone is 8b, with parts of the Downtown area falling into zone 9a.[83]

Winters are cool, cloudy, and rainy. The coldest month is December with an average daily high of 46.9 °F (8.3 °C), although overnight lows usually remain above freezing by a few degrees. Evening temperatures fall to or below freezing 32 nights per year on average, but very rarely to or below 18 °F (−8 °C). There are only 2.1 days per year where the daytime high temperature fails to rise above freezing. The infrequency of cold waves renders the mean for the coldest high to be at the exact freezing point of 32 °F (0 °C).[84] The lowest overnight temperature ever recorded was −3 °F (−19 °C),[83] on February 2, 1950,[84] while the coldest daytime high temperature ever recorded was 14 °F (−10 °C) on December 30, 1968.[84] The average window for freezing temperatures to potentially occur is between November 15 and March 19, allowing a growing season of 240 days.[84]

Annual snowfall in Portland is 4.3 inches (10.9 cm), which usually falls during the December-to-March time frame.[85] The city of Portland avoids snow more frequently than its suburbs, due in part to its low elevation and urban heat island effect. Neighborhoods outside of the downtown core, especially in slightly higher elevations near the West Hills and Mount Tabor, can experience a dusting of snow while downtown receives no accumulation at all. The city has experienced a few major snow and ice storms in its past with extreme totals having reached 44.5 in (113 cm) at the airport in 1949–50 and 60.9 in (155 cm) at downtown in 1892–93.[86][87]

Summers in Portland are warm, dry, and sunny, though the sunny warm weather is short lived from mid June through early September.[88] The months of June, July, August and September account for a combined 4.19 inches (106 mm) of total rainfall – only 11% of the 36.91 in (938 mm) of the precipitation that falls throughout the year. The warmest month is August, with an average high temperature of 82.3 °F (27.9 °C). Because of its inland location 70 miles (110 km) from the coast, as well as the protective nature of the Oregon Coast Range to its west, Portland summers are less susceptible to the moderating influence of the nearby Pacific Ocean. Consequently, Portland experiences heat waves on rare occasion, with temperatures rising into the 90 °F (32 °C) for a few days. However, on average, temperatures reach or exceed 80 °F (27 °C) on only 61 days per year, of which 15 days will reach 90 °F (32 °C) and only 1.3 days will reach 100 °F (38 °C). The most 90-degree days ever recorded in one year is 31, which happened in 2018.[89]

On June 28, 2021, Portland recorded its all-time record high of 116 °F (47 °C) and its warmest daily low temperature of 75 °F (24 °C),[90][non-primary source needed][91][84][92] during the 2021 Western North America heat wave. A temperature of 100 °F (38 °C) has been recorded in all five months from May through September. The warmest night of the year averages 68 °F (20 °C).[84]

Spring and fall can bring variable weather including high-pressure ridging that sends temperatures surging above 80 °F (27 °C) and cold fronts that plunge daytime temperatures into the 40s °F (4–9 °C). However, lengthy stretches of overcast days beginning in mid-fall and continuing into mid-spring are most common. Rain often falls as a light drizzle for several consecutive days at a time, contributing to 155 days on average with measurable (≥0.01 in or 0.25 mm) precipitation annually. Temperatures have reached 90 °F (32 °C) as early as April 30 and as late as October 5, while 80 °F (27 °C) has been reached as early as April 1 and as late as October 21. Severe weather, such as thunder and lightning, is uncommon and tornadoes are exceptionally rare, although not impossible.[93][94]

| Climate data for Portland, Oregon (PDX), 1991–2020 normals,[lower-alpha 2] snow days 1981-2010, extremes 1940–present[lower-alpha 3] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 66 (19) |

71 (22) |

80 (27) |

90 (32) |

100 (38) |

116 (47) |

107 (42) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

92 (33) |

73 (23) |

65 (18) |

116 (47) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.1 (14.5) |

60.1 (15.6) |

69.6 (20.9) |

78.4 (25.8) |

86.8 (30.4) |

91.7 (33.2) |

96.7 (35.9) |

96.7 (35.9) |

91.2 (32.9) |

77.6 (25.3) |

63.8 (17.7) |

58.3 (14.6) |

100.0 (37.8) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 47.5 (8.6) |

51.5 (10.8) |

56.8 (13.8) |

62.0 (16.7) |

69.3 (20.7) |

74.3 (23.5) |

81.9 (27.7) |

82.3 (27.9) |

76.7 (24.8) |

64.4 (18.0) |

53.5 (11.9) |

46.9 (8.3) |

63.9 (17.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 36.2 (2.3) |

36.8 (2.7) |

39.7 (4.3) |

43.7 (6.5) |

49.4 (9.7) |

54.1 (12.3) |

58.5 (14.7) |

58.9 (14.9) |

54.1 (12.3) |

46.7 (8.2) |

40.6 (4.8) |

36.2 (2.3) |

46.2 (7.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 25.1 (−3.8) |

25.9 (−3.4) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

34.8 (1.6) |

40.5 (4.7) |

47.3 (8.5) |

52.3 (11.3) |

51.7 (10.9) |

45.7 (7.6) |

35.9 (2.2) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

−3 (−19) |

19 (−7) |

29 (−2) |

29 (−2) |

39 (4) |

43 (6) |

44 (7) |

34 (1) |

26 (−3) |

13 (−11) |

6 (−14) |

−3 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.03 (128) |

3.68 (93) |

3.97 (101) |

2.89 (73) |

2.51 (64) |

1.63 (41) |

0.50 (13) |

0.54 (14) |

1.52 (39) |

3.42 (87) |

5.45 (138) |

5.77 (147) |

36.91 (938) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.7 (4.3) |

1.2 (3.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.04 (0.10) |

1.3 (3.3) |

4.3 (11) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 18.6 | 15.5 | 17.7 | 17.2 | 13.0 | 9.1 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 6.6 | 13.5 | 18.3 | 19.2 | 155.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 4.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 80.9 | 78.0 | 74.6 | 71.6 | 68.7 | 65.8 | 62.8 | 64.8 | 69.4 | 77.9 | 81.5 | 82.7 | 73.2 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 33.6 (0.9) |

36.1 (2.3) |

38.3 (3.5) |

40.8 (4.9) |

45.3 (7.4) |

49.8 (9.9) |

52.9 (11.6) |

53.8 (12.1) |

50.7 (10.4) |

46.2 (7.9) |

40.3 (4.6) |

35.1 (1.7) |

43.6 (6.4) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 85.6 | 116.4 | 191.1 | 221.1 | 276.1 | 290.2 | 331.9 | 298.1 | 235.7 | 151.7 | 79.3 | 63.7 | 2,340.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 30 | 40 | 52 | 54 | 60 | 62 | 70 | 68 | 63 | 45 | 28 | 23 | 52 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity, dewpoint and sun 1961–1990)[84][96][97] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas [98] (UV index) | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Portland's cityscape derives much of its character from the many bridges that span the Willamette River downtown, several of which are historic landmarks, and Portland has been nicknamed "Bridgetown" for many decades as a result.[49] Three of downtown's most heavily used bridges are more than 100 years old and are designated historic landmarks: Hawthorne Bridge (1910), Steel Bridge (1912), and Broadway Bridge (1913). Portland's newest bridge in the downtown area, Tilikum Crossing, opened in 2015 and is the first new bridge to span the Willamette in Portland since the 1973 opening of the double-decker Fremont Bridge.[99]

Other bridges that span the Willamette River in the downtown area include the Burnside Bridge, the Ross Island Bridge (both built 1926), and the double-decker Marquam Bridge (built 1966). Other bridges outside the downtown area include the Sellwood Bridge (built 2016) to the south; and the St. Johns Bridge, a Gothic revival suspension bridge built in 1931, to the north. The Glenn L. Jackson Memorial Bridge and the Interstate Bridge provide access from Portland across the Columbia River into Washington state.

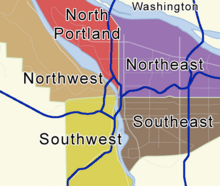

Neighborhoods

The Willamette River, which flows north through downtown, serves as the natural boundary between East and West Portland. The denser and earlier-developed west side extends into the lap of the West Hills, while the flatter east side extends for roughly 180 blocks until it meets the suburb of Gresham. In 1891 the cities of Portland, Albina, and East Portland were consolidated, creating inconsistent patterns of street names and addresses. It was not unusual for a street name to be duplicated in disparate areas. The "Great Renumbering" on September 2, 1931, standardized street naming patterns and divided Portland into five "general districts." It also changed house numbers from 20 per block to 100 per block and adopted a single street name on a grid. For example, the 200 block north of Burnside is either NW Davis Street or NE Davis Street throughout the entire city.[100]

The five previous addressing sections of Portland, which were colloquially known as quadrants despite there being five,[101][102] have developed distinctive identities, with mild cultural differences and friendly rivalries between their residents, especially between those who live east of the Willamette River versus west of the river.[103] Portland's addressing sections are North, Northwest, Northeast, South, Southeast, and Southwest (which includes downtown Portland). The Willamette River divides the city into east and west while Burnside Street, which traverses the entire city lengthwise, divides the north and south. North Portland consists of the peninsula formed by the Willamette and Columbia Rivers, with N Williams Ave serving as its eastern boundary. All addresses and streets within the city are prefixed by N, NW, NE, SW or SE with the exception of Burnside Street, which is prefixed with W or E. Starting on May 1, 2020, former Southwest prefix addresses with house numbers on east–west streets leading with zero dropped the zero and the street prefix on all streets (including north–south streets) converted from Southwest to South. For example, the current address of 246 S. California St. was changed from 0246 SW California St. and the current address of 4310 S. Macadam Ave. was converted from 4310 SW Macadam Ave. effective on May 1, 2020.

The new South Portland addressing section was approved by the Portland City Council on June 6, 2018[104] and is bounded by SW Naito Parkway SW View Point Terrace and Tryon Creek State Natural Area to the west, SW Clay Street to the north and the Clackamas County line to the south. It includes the Lair Hill, Johns Landing and South Waterfront districts and Lewis & Clark College as well as the Riverdale area of unincorporated Multnomah County south of the Portland city limits. [105] In 2018, the city's Bureau of Transportation finalized a plan to transition this part of Portland into South Portland, beginning on May 1, 2020, to reduce confusion by 9-1-1 dispatchers and delivery services.[106] With the addition of South Portland, all six addressing sectors (N, NE, NW, S, SE and SW) are now officially known as sextants.[107]

The Pearl District in Northwest Portland, which was largely occupied by warehouses, light industry and railroad classification yards in the early to mid-20th century, now houses upscale art galleries, restaurants, and retail stores, and is one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the city.[108] Areas further west of the Pearl District include neighborhoods known as Uptown and Nob Hill, as well as the Alphabet District and NW 23rd Ave., a major shopping street lined with clothing boutiques and other upscale retail, mixed with cafes and restaurants.[109]

Northeast Portland is home to the Lloyd District, Alberta Arts District, and the Hollywood District.

North Portland is largely residential and industrial. It contains Kelley Point Park, the northernmost point of the city. It also contains the St. Johns neighborhood, which is historically one of the most ethnically diverse and poorest neighborhoods in the city.[110]

Old Town Chinatown is next to the Pearl District in Northwest Portland. In 1890 it was the second largest Chinese community in the United States.[111] In 2017, the crime rate was several times above the city average. This neighborhood has been called Portland's skid row.[112] Southwest Portland is largely residential. Downtown district, made up of commercial businesses, museums, skyscrapers, and public landmarks represents a small area within the southwest address section. Portland's South Waterfront area has been developing into a dense neighborhood of shops, condominiums, and apartments starting in the mid-2000s. Development in this area is ongoing.[113] The area is served by the Portland Streetcar, the MAX Orange Line and four TriMet bus lines. This former industrial area sat as a brownfield prior to development in the mid-2000s.[114]

Southeast Portland is largely residential, and consists of several neighborhoods, including Hawthorne District, Belmont, Brooklyn, and Mount Tabor. Reed College, a private liberal arts college that was founded in 1908, is located within the confines of Southeast Portland as is Mount Tabor, a volcanic landform.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 2,874 | — | |

| 1870 | 8,293 | 188.6% | |

| 1880 | 17,577 | 111.9% | |

| 1890 | 46,385 | 163.9% | |

| 1900 | 90,426 | 94.9% | |

| 1910 | 207,214 | 129.2% | |

| 1920 | 258,288 | 24.6% | |

| 1930 | 301,815 | 16.9% | |

| 1940 | 305,394 | 1.2% | |

| 1950 | 373,628 | 22.3% | |

| 1960 | 372,676 | −0.3% | |

| 1970 | 382,619 | 2.7% | |

| 1980 | 366,383 | −4.2% | |

| 1990 | 437,319 | 19.4% | |

| 2000 | 529,121 | 21.0% | |

| 2010 | 583,776 | 10.3% | |

| 2020 | 652,503 | 11.8% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 641,162 | [115] | −1.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[116] 2010–2020[9][6] | |||

| Demographic profile | 2020 | 2010[117] | 1990[118] | 1970[118] | 1940[118] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 77.4% | 76.1% | 84.6% | 92.2% | 98.1% |

| Non-Hispanic White | 70.6% | 72.2% | 82.9% | 90.7%[119] | — |

| Black or African American | 5.8% | 6.3% | 7.7% | 5.6% | 0.6% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 9.7% | 9.4% | 3.2% | 1.7%[119] | — |

| Asian | 8.2% | 7.1% | 5.3% | 1.3% | 1.2% |

![Graph showing the city's population growth from 1850 to 2010[120]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/37/Portland_population_growth.png/200px-Portland_population_growth.png)

Racial Makeup of Portland (2019)[121]

The 2010 census reported the city as 76.1% White (444,254 people), 7.1% Asian (41,448), 6.3% Black or African American (36,778), 1.0% Native American (5,838), 0.5% Pacific Islander (2,919), 4.7% belonging to two or more racial groups (24,437) and 5.0% from other races (28,987).[117] 9.4% were Hispanic or Latino, of any race (54,840). Whites not of Hispanic origin made up 72.2% of the total population.[117]

In 1940, Portland's African-American population was approximately 2,000 and largely consisted of railroad employees and their families.[122] During the war-time Liberty Ship construction boom, the need for workers drew many blacks to the city. The new influx of blacks settled in specific neighborhoods, such as the Albina district and Vanport. The May 1948 flood which destroyed Vanport eliminated the only integrated neighborhood, and an influx of blacks into the northeast quadrant of the city continued.[122] Portland's longshoremen racial mix was described as being "lily-white" in the 1960s when the local International Longshore and Warehouse Union declined to represent grain handlers since some were black.[123]

Over two-thirds of Oregon's African-American residents live in Portland.[122] As of the 2000 census, three of its high schools (Cleveland, Lincoln and Wilson) were over 70% White, reflecting the overall population, while Jefferson High School was 87% non-White. The remaining six schools have a higher number of non-Whites, including Blacks and Asians. Hispanic students average from 3.3% at Wilson to 31% at Roosevelt.[124]

Portland residents identifying solely as Asian Americans account for 7.1% of the population; an additional 1.8% is partially of Asian heritage. Vietnamese Americans make up 2.2% of Portland's population, and make up the largest Asian ethnic group in the city, followed by Chinese (1.7%), Filipinos (0.6%), Japanese (0.5%), Koreans (0.4%), Laotians (0.4%), Hmong (0.2%), and Cambodians (0.1%).[125] A small population of Iu Mien live in Portland. Portland has two Chinatowns, with New Chinatown in the 'Jade District' along SE 82nd Avenue with Chinese supermarkets, Hong Kong style noodle houses, dim sum, and Vietnamese phở restaurants.[126]

With about 12,000 Vietnamese residing in the city proper, Portland has one of the largest Vietnamese populations in America per capita.[127] According to statistics, there are over 4,500 Pacific Islanders in Portland, making up 0.7% of the city's population.[128] There is a Tongan community in Portland, who arrived in the area in the 1970s, and Tongans and Pacific Islanders as a whole are one of the fastest-growing ethnic groups in the Portland area.[129]

Portland's population has been and remains predominantly White. In 1940, Whites were over 98% of the city's population.[130] In 2009, Portland had the fifth-highest percentage of White residents among the 40 largest U.S. metropolitan areas. A 2007 survey of the 40 largest cities in the U.S. concluded Portland's urban core has the highest percentage of White residents.[131] Some scholars have noted the Pacific Northwest as a whole is "one of the last Caucasian bastions of the United States".[132] While Portland's diversity was historically comparable to metro Seattle and Salt Lake City, those areas grew more diverse in the late 1990s and 2000s. Portland not only remains White, but migration to Portland is disproportionately White.[131][133]

The Oregon Territory banned African American settlement in 1849. In the 19th century, certain laws allowed the immigration of Chinese laborers but prohibited them from owning property or bringing their families.[131][134][135] The early 1920s saw the rapid growth of the Ku Klux Klan, which became very influential in Oregon politics, culminating in the election of Walter M. Pierce as governor.[134][135][136]

The largest influxes of minority populations occurred during World War II, as the African American population grew by a factor of 10 for wartime work.[131] After World War II, the Vanport flood in 1948 displaced many African Americans. As they resettled, redlining directed the displaced workers from the wartime settlement to neighboring Albina.[132][135][137] There and elsewhere in Portland, they experienced police hostility, lack of employment, and mortgage discrimination, leading to half the black population leaving after the war.[131]

In the 1980s and 1990s, radical skinhead groups flourished in Portland.[135] In 1988, Mulugeta Seraw, an Ethiopian immigrant, was killed by three skinheads. The response to his murder involved a community-driven series of rallies, campaigns, nonprofits and events designed to address Portland's racial history, leading to a city considered significantly more tolerant than in 1988 at Seraw's death.[138]

Portland has a substantial Roma population.[139]

76% of Latinos in Portland are of Mexican heritage.[140]

Households

As of the 2010 census, there were 583,776 people living in the city, organized into 235,508 households. The population density was 4,375.2 people per square mile. There were 265,439 housing units at an average density of 1989.4 per square mile (1,236.3/km2). Population growth in Portland increased 10.3% between 2000 and 2010.[141] Population growth in the Portland metropolitan area has outpaced the national average during the last decade, and this is expected to continue over the next 50 years.[142]

Out of 223,737 households, 24.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.1% were married couples living together, 10.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 47.1% were non-families. 34.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.3 and the average family size was 3. The age distribution was 21.1% under the age of 18, 10.3% from 18 to 24, 34.7% from 25 to 44, 22.4% from 45 to 64, and 11.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $40,146, and the median income for a family was $50,271. Males had a reported median income of $35,279 versus $29,344 reported for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,643. 13.1% of the population and 8.5% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 15.7% of those under the age of 18 and 10.4% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line. Figures delineating the income levels based on race are not available at this time. According to the Modern Language Association, in 2010 80.9% (539,885) percent of Multnomah County residents ages 5 and over spoke English as their primary language at home.[143] 8.1% of the population spoke Spanish (54,036), with Vietnamese speakers making up 1.9%, and Russian 1.5%.[143]

Social

The Portland metropolitan area has historically had a significant LGBT population throughout the late 20th and early 21st century.[144][145] In 2015, the city metro had the second highest percentage of LGBT residents in the United States with 5.4% of residents identifying as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender, second only to San Francisco.[146] In 2006, it was reported to have the seventh highest LGBT population in the country, with 8.8% of residents identifying as gay, lesbian, or bisexual, and the metro ranking fourth in the nation at 6.1%.[147] The city held its first pride festival in 1975 on the Portland State University campus.[148]

Religion

Portland has been cited as the least religious city in the United States with over 42% of residents identifying as religiously "unaffiliated",[149] according to the nonpartisan and nonprofit Public Religion Research Institute's American Values Atlas.[150]

Homelessness

A 2019 survey by the city's budget office showed that homelessness is perceived as the top challenge facing Portland, and was cited as a reason people move and do not participate in park programs.[151] Calls to 911 concerning "unwanted persons" have significantly increased between 2013 and 2018, and the police are increasingly dealing with homeless and mentally ill.[152] It is taking a toll on sense of safety among visitors and residents and business owners are adversely impacted.[153] Even though homeless services and shelter beds have increased, as of 2020 homelessness is considered an intractable problem in Portland.[154]

The proposed budget for 2022–23 includes $5.8MM to buy land for affordable housing, and $36MM to equip and operate "safe rest villages".[155]

Crime

According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Uniform Crime Report in 2009, Portland ranked 53rd in violent crime out of the top 75 U.S. cities with a population greater than 250,000.[156] The murder rate in Portland in 2013 averaged 2.3 murders per 100,000 people per year, which was lower than the national average. In 2011, 72% of arrested male subjects tested positive for illegal drugs and the city was dubbed the "deadliest drug market in the Pacific Northwest" due to drug related deaths.[157] In 2010, ABC's Nightline reported that Portland is one of the largest hubs for child sex trafficking.[158]

In the Portland Metropolitan statistical area which includes Clackamas, Columbia, Multnomah, Washington, and Yamhill Counties, OR and Clark and Skamania Counties, WA for 2017, the murder rate was 2.6, violent crime was 283.2 per 100,000 people per year. In 2017, the population within the city of Portland was 649,408 and there were 24 murders and 3,349 violent crimes.[159]

In the first quarter of 2021, Portland recorded the largest increase in homicides of any American city during that time period. There were 21 homicides, an increase of 950 percent over that same quarter the year before.[160]

Below is a sortable table containing violent crime data from each Portland neighborhood during the calendar year of 2014.

| Violent Crime by Neighborhood in Portland (2014)[161] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totals | Per 100,000 residents | ||||||||

| Neighborhood | Population | Aggravated Assault | Homicide | Rape | Robbery | Aggravated Assault | Homicide | Rape | Robbery |

| Alameda | 5,214 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 19.2 | 0.0 | 19.2 | 19.2 |

| Arbor Lodge | 6,153 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 130.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 227.5 |

| Ardenwald-Johnson Creek | 4,748 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 21.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Argay | 6,006 | 19 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 316.4 | 0.0 | 33.3 | 199.8 |

| Arlington Heights | 718 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 139.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 139.3 |

| Arnold Creek | 3,125 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Ashcreek | 5,719 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 69.9 | 17.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Beaumont-Wilshire | 5,346 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Boise | 3,311 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 332.2 | 0.0 | 30.2 | 120.8 |

| Brentwood-Darlington | 12,994 | 30 | 0 | 5 | 12 | 230.9 | 0.0 | 38.5 | 92.4 |

| Bridgeton | 725 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 137.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Bridlemile | 5,481 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 36.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 18.2 |

| Brooklyn | 3,485 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 172.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 114.8 |

| Buckman | 8,472 | 46 | 0 | 4 | 19 | 543.0 | 0.0 | 47.2 | 224.3 |

| Cathedral Park | 3,349 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 238.9 | 0.0 | 29.9 | 29.9 |

| Centennial | 23,662 | 94 | 2 | 7 | 28 | 397.3 | 8.5 | 29.6 | 118.3 |

| Collins View | 3,036 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Concordia | 9,550 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 83.8 | 0.0 | 10.5 | 62.8 |

| Creston-Kenilworth | 8,227 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.2 |

| Crestwood | 1,047 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1146.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 668.6 |

| Cully | 13,209 | 47 | 2 | 9 | 25 | 355.8 | 15.1 | 68.1 | 189.3 |

| Downtown | 12,801 | 95 | 1 | 10 | 75 | 742.1 | 7.8 | 78.1 | 585.9 |

| East Columbia | 1,748 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 743.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 743.7 |

| Eastmoreland | 5,007 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 | 0.0 |

| Eliot | 3,611 | 19 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 526.2 | 0.0 | 83.1 | 249.2 |

| Far Southwest | 1,320 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 75.8 | 0.0 | 75.8 | 0.0 |

| Forest Park | 4,129 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Foster-Powell | 7,335 | 19 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 259.0 | 0.0 | 27.3 | 109.1 |

| Glenfair | 3,417 | 18 | 0 | 3 | 14 | 526.8 | 0.0 | 87.8 | 409.7 |

| Goose Hollow | 6,507 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 215.2 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 138.3 |

| Grant Park | 3,937 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 127.0 | 0.0 | 25.4 | 0.0 |

| Hayden Island | 2,270 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 352.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 440.5 |

| Hayhurst | 5,382 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 74.3 | 0.0 | 18.6 | 0.0 |

| Hazelwood | 23,462 | 116 | 3 | 13 | 50 | 494.4 | 12.8 | 55.4 | 213.1 |

| Healy Heights | 187 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Hillsdale | 7,540 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 0.0 |

| Hillside | 2,200 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Hollywood | 1,578 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 633.7 | 0.0 | 63.4 | 507.0 |

| Homestead | 2,009 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 149.3 | 0.0 | 149.3 | 0.0 |

| Hosford-Abernethy | 7,336 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 95.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 81.8 |

| Humboldt | 5,110 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 567.5 | 19.6 | 0.0 | 97.8 |

| Irvington | 8,501 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 117.6 | 0.0 | 35.3 | 35.3 |

| Kenton | 7,272 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 330.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 247.5 |

| Kerns | 5,340 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 168.5 | 0.0 | 37.5 | 112.4 |

| King | 6,149 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 309.0 | 0.0 | 16.3 | 195.2 |

| Laurelhurst | 4,633 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 64.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 43.2 |

| Lents | 20,465 | 73 | 2 | 7 | 41 | 356.7 | 9.8 | 34.2 | 200.3 |

| Linnton | 941 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 106.3 | 0.0 | 318.8 | 0.0 |

| Lloyd District | 1,142 | 21 | 1 | 6 | 42 | 1838.9 | 87.6 | 525.4 | 3677.8 |

| Madison South | 7,130 | 21 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 294.5 | 0.0 | 28.1 | 154.3 |

| Maplewood | 2,557 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 39.1 |

| Markham | 2,248 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 44.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Marshall Park | 1,248 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Mill Park | 8,650 | 31 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 358.4 | 0.0 | 34.7 | 115.6 |

| Montavilla | 16,287 | 49 | 0 | 2 | 30 | 300.9 | 0.0 | 12.3 | 184.2 |

| Mount Scott-Arleta | 7,397 | 18 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 243.3 | 0.0 | 54.1 | 94.6 |

| Mount Tabor | 10,162 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 39.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.7 |

| Multnomah | 7,409 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 13.5 | 0.0 | 27.0 | 27.0 |

| North Tabor | 5,163 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 154.9 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 77.5 |

| Northwest District | 13,399 | 25 | 0 | 3 | 19 | 186.6 | 0.0 | 22.4 | 141.8 |

| Northwest Heights | 4,806 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Old Town-Chinatown | 3,922 | 106 | 1 | 6 | 47 | 2702.7 | 25.5 | 153.0 | 1198.4 |

| Overlook | 6,093 | 16 | 0 | 5 | 12 | 262.6 | 0.0 | 82.1 | 196.9 |

| Parkrose | 6,363 | 52 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 817.2 | 15.7 | 62.9 | 94.3 |

| Parkrose Heights | 6,119 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 196.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 163.4 |

| Pearl | 5,997 | 19 | 0 | 4 | 19 | 316.8 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 316.8 |

| Piedmont | 7,025 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 199.3 | 0.0 | 28.5 | 42.7 |

| Pleasant Valley | 12,743 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 70.6 | 0.0 | 15.7 | 0.0 |

| Portsmouth | 9,789 | 37 | 3 | 6 | 13 | 378.0 | 30.6 | 61.3 | 132.8 |

| Powellhurst-Gilbert | 30,639 | 124 | 2 | 8 | 48 | 404.7 | 6.5 | 26.1 | 156.7 |

| Reed | 4,399 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 113.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Richmond | 11,607 | 13 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 112.0 | 8.6 | 25.8 | 60.3 |

| Rose City Park | 8,982 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 66.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 89.1 |

| Roseway | 6,323 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 221.4 | 15.8 | 0.0 | 47.4 |

| Russell | 3,175 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 94.5 | 0.0 | 31.5 | 63.0 |

| Sabin | 4,149 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 216.9 | 0.0 | 24.1 | 72.3 |

| Sellwood-Moreland | 11,621 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 43.0 | 0.0 | 17.2 | 17.2 |

| South Burlingame | 1,747 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 229.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| South Portland | 6,631 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 60.3 | 0.0 | 15.1 | 60.3 |

| South Tabor | 5,995 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 150.1 | 0.0 | 33.4 | 33.4 |

| Southwest Hills | 8,389 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 23.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| St. Johns | 12,207 | 51 | 0 | 5 | 18 | 417.8 | 0.0 | 41.0 | 147.5 |

| Sullivan's Gulch | 3,139 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 223.0 | 0.0 | 31.9 | 191.1 |

| Sumner | 2,137 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 655.1 | 0.0 | 46.8 | 187.2 |

| Sunderland | 718 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 278.6 | 0.0 | 139.3 | 139.3 |

| Sunnyside | 7,354 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 122.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 68.0 |

| Sylvan-Highlands | 1,317 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 75.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 151.9 |

| University Park | 6,035 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 149.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 116.0 |

| Vernon | 2,585 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 232.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 270.8 |

| West Portland Park | 3,921 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 153.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 25.5 |

| Wilkes | 8,775 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 170.9 | 0.0 | 45.6 | 79.8 |

| Woodland Park | 176 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 568.2 | 568.2 |

| Woodlawn | 4,933 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 344.6 | 0.0 | 20.3 | 162.2 |

| Woodstock | 8,942 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 123.0 | 22.4 | 11.2 | 123.0 |

Economy

Portland's location is beneficial for several industries. Relatively low energy cost, accessible resources, north–south and east–west Interstates, international air terminals, large marine shipping facilities, and both west coast intercontinental railroads are all economic advantages.[162]

The city's marine terminals alone handle over 13 million tons of cargo per year, and the port is home to one of the largest commercial dry docks in the country.[163][164] The Port of Portland is the third-largest export tonnage port on the west coast of the U.S., and being about 80 miles (130 km) upriver, it is the largest fresh-water port.[162]

The scrap steel industry's history in Portland predates World War II. By the 1950s, the scrap steel industry became the city's number one industry for employment. The scrap steel industry thrives in the region, with Schnitzer Steel Industries, a prominent scrap steel company, shipping a record 1.15 billion tons of scrap metal to Asia during 2003. Other heavy industry companies include ESCO Corporation and Oregon Steel Mills.[165][166]

Technology is a major component of the city's economy, with more than 1,200 technology companies existing within the metro.[162] This high density of technology companies has led to the nickname Silicon Forest being used to describe the Portland area, a reference to the abundance of trees in the region and to the Silicon Valley region in Northern California.[167] The area also hosts facilities for software companies and online startup companies, some supported by local seed funding organizations and business incubators.[168] Computer components manufacturer Intel is the Portland area's largest employer, providing jobs for more than 15,000 people, with several campuses to the west of central Portland in the city of Hillsboro.[162]

The Portland metro area has become a business cluster for athletic/outdoor gear and footwear manufacturer's headquarters. Shoes are not manufactured in Portland.[169] The area is home to the global, North American or U.S. headquarters of Nike (the only Fortune 500 company headquartered in Oregon), Adidas, Columbia Sportswear, LaCrosse Footwear, Dr. Martens, Li-Ning,[170] Keen,[171] and Hi-Tec Sports.[172] While headquartered elsewhere, Merrell, Amer Sports and Under Armour have design studios and local offices in the Portland area.

Other notable Portland-based companies include industrial goods and metal fabrication company Precision Castparts, film animation studio Laika; commercial vehicle manufacturer Daimler Trucks North America; advertising firm Wieden+Kennedy; bankers Umpqua Holdings; child care and early childhood education provider KinderCare Learning Centers; and retailers Fred Meyer, New Seasons Market, and Storables.

Breweries are another major industry in Portland, which is home to 139 breweries/microbreweries, the 7th most in the nation, as of December 2018.[173] Additionally, the city boasts a robust coffee culture that now rivals Seattle and hosts over 20 coffee roasters.[174]

Housing

In 2016, home prices in Portland grew faster than in any other city in the United States.[175] Apartment rental costs in Portland reported in November 2019 was $1,337 for two bedroom and $1,133 for one bedroom.[176]

In 2017, developers projected an additional 6,500 apartments to be built in the Portland Metro Area over the next year.[177] However, as of December 2019, the number of homes available for rent or purchase in Portland continues to shrink. Over the past year, housing prices in Portland have risen 2.5%. Housing prices in Portland continue to rise, the median price rising from $391,400 in November 2018 to $415,000 in November 2019.[178] There has been a rise of people from out of state moving to Portland, which impacts housing availability. Because of the demand for affordable housing and influx of new residents, more Portlanders in their 20s and 30s are still living in their parents' homes.[179]

Arts and culture

Music, film, and performing arts

Portland is home to a range of classical performing arts institutions, including the Portland Opera, the Oregon Symphony, and the Portland Youth Philharmonic; the last of these, established in 1924, was the first youth orchestra established in the United States.[180] The city is also home to several theaters and performing arts institutions, including the Oregon Ballet Theatre, Northwest Children's Theatre, Portland Center Stage, Artists Repertory Theatre and Miracle Theatre.

In 2013, The Guardian named the city's music scene as one of the "most vibrant" in the United States.[181] Portland is home to famous bands, such as the Kingsmen and Paul Revere & the Raiders, both famous for their association with the song "Louie Louie" (1963).[182] Other widely known musical groups include the Dandy Warhols, Quarterflash, Everclear, Pink Martini, Sleater-Kinney, Blitzen Trapper, the Decemberists, and the late Elliott Smith. More recently, Portugal. The Man, Modest Mouse, and the Shins have made their home in Portland. In the 1980s, the city was home to a burgeoning punk scene, which included bands such as the Wipers and Dead Moon.[183] The city's now-demolished Satyricon nightclub was a punk venue notorious for being the place where Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain first encountered his future wife and Hole frontwoman Courtney Love in 1990.[184] Love was then a resident of Portland and started several bands there with Kat Bjelland, later of Babes in Toyland.[185][186] Multi-Grammy award-winning jazz artist Esperanza Spalding is from Portland and performed with the Chamber Music Society of Oregon at a young age.[187]

A wide range of films have been shot in Portland, from various independent features to major big-budget productions. Director Gus Van Sant has notably set and shot many of his films in the city.[188] The city has also been featured in various television programs, notably the IFC sketch comedy series Portlandia. The series, which ran for eight seasons from 2011 to 2018,[189] was shot on location in Portland, and satirized the city as a hub of liberal politics, organic food, alternative lifestyles, and anti-establishment attitudes.[190] MTV's long-time running reality show The Real World was also shot in Portland for the show's 29th season: The Real World: Portland premiered on MTV in 2013.[191] Other television series shot in the city include Leverage, The Librarians,[192] Under Suspicion, Grimm, and Nowhere Man.[193]

An unusual feature of Portland entertainment is the large number of movie theaters serving beer, often with second-run or revival films.[194] Notable examples of these "brew and view" theaters include the Bagdad Theater and Pub, a former vaudeville theater built in 1927 by Universal Studios;[195] Cinema 21; and the Laurelhurst Theater, in operation since 1923. Portland hosts the world's longest-running H. P. Lovecraft Film Festival[196] at the Hollywood Theatre.[197]

Museums and recreation

Portland is home to numerous museums and educational institutions, ranging from art museums to institutions devoted to science and wildlife. Among the science-oriented institutions are the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI), which consists of five main halls and other ticketed attractions, such as the USS Blueback submarine,[198] the ultra-large-screen Empirical Theater (which replaced an OMNIMAX theater in 2013),[199] and the Kendall Planetarium.[200] The World Forestry Center Discovery Museum, located in the city's Washington Park area, offers educational exhibits on forests and forest-related subjects. Also located in Washington Park are the Hoyt Arboretum, the International Rose Test Garden, the Japanese Garden, and the Oregon Zoo.[201]

The Portland Art Museum owns the city's largest art collection and presents a variety of touring exhibitions each year and, with the recent addition of the Modern and Contemporary Art wing, it became one of the United States' 25 largest museums. The Oregon Historical Society Museum, founded in 1898, which has a variety of books, film, pictures, artifacts, and maps dating back throughout Oregon's history. It houses permanent and temporary exhibits about Oregon history, and hosts traveling exhibits about the history of the United States.[202]

Oaks Amusement Park, in the Sellwood district of Southeast Portland, is the city's only amusement park and is also one of the country's longest-running amusement parks. It has operated since 1905 and was known as the "Coney Island of the Northwest" upon its opening.[203]

Cuisine and breweries

Food carts are extremely popular within the city, with over 600 licensed carts.[204][205] The city is home to Stumptown Coffee Roasters as well as dozens of other micro-roasteries and cafes.[206]

Portland has 58 active breweries within city limits,[207] and 70+ within the surrounding metro area.[207] and data compiled by the Brewers Association ranks Portland seventh in the United States as of 2018.[208]

Portland hosts a number of festivals throughout the year that celebrate beer and brewing, including the Oregon Brewers Festival, held in Tom McCall Waterfront Park. Held each summer during the last full weekend of July, it is the largest outdoor craft beer festival in North America, with over 70,000 attendees in 2008.[209] Other major beer festivals throughout the calendar year include the Spring Beer and Wine Festival in April, the North American Organic Brewers Festival in June, the Portland International Beerfest in July,[210] and the Holiday Ale Festival in December.

Sustainability

The city became a pioneer of state-directed metropolitan planning, a program which was instituted statewide in 1969 to compact the urban growth boundaries of the city.[211] Portland was the first city to enact a comprehensive plan to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.[212]

Free speech and public nudity

Strong free speech protections of the Oregon Constitution upheld by the Oregon Supreme Court in State v. Henry,[213] specifically found that full nudity and lap dances in strip clubs are protected speech.[214] Portland has the highest number of strip clubs per-capita in a city in the United States, and Oregon ranks as the highest state for per-capita strip clubs.[215]

In November 2008, a Multnomah County judge dismissed charges against a nude bicyclist arrested on June 26, 2008. The judge stated that the city's annual World Naked Bike Ride – held each year in June since 2004 – has created a "well-established tradition" in Portland where cyclists may ride naked as a form of protest against cars and fossil fuel dependence.[216] The defendant was not riding in the official World Naked Bike Ride at the time of his arrest as it had occurred 12 days earlier that year, on June 14.[217]

Protests

From November 10 to 12, 2016, protests in Portland turned into a riot, when a group broke off from a larger group of peaceful protesters who were opposed to the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States.[218][219]

Public Art

.

Sports

Portland is home to three major league sports franchises: the Portland Trail Blazers of the NBA, the Portland Timbers of Major League Soccer (MLS), and the Portland Thorns FC of the National Women's Soccer League. In 2015, the Timbers won the MLS Cup, which was the first male professional sports championship for a team from Portland since the Trail Blazers won the NBA championship in 1977.[220] Despite being the 19th most populated metro area in the United States, Portland contains only one franchise from the NFL, NBA, NHL, or MLB, making it United States second most populated metro area with that distinction, behind San Antonio. The city has been often rumored to receive an additional franchise, although efforts to acquire a team have failed due to stadium funding issues.[221] An organization known as the Portland Diamond Project (PDP)[222] has worked with the MLB and local government, and there are plans to have an MLB stadium constructed in the industrial district of Portland.[223] The PDP has not yet received the funding for this project.

Portland sports fans are characterized by their passionate support. The Trail Blazers sold out every home game between 1977 and 1995, a span of 814 consecutive games, the second-longest streak in American sports history.[224] The Timbers joined MLS in 2011 and have sold out every home match since joining the league, a streak that has now reached 70+ matches.[225] The Timbers season ticket waiting list has reached 10,000+, the longest waiting list in MLS.[226] In 2015, they became the first team in the Northwest to win the MLS Cup. Player Diego Valeri marked a new record for fastest goal in MLS Cup history at 27 seconds into the game.[227]

The annual Cambia Portland Classic women's golf tournament in September, now in its 50th year, is the longest-running non-major tournament on the LPGA Tour, plays in the southern suburb of West Linn.[228]

Two rival universities exist within Portland city limits: the University of Portland Pilots and the Portland State University Vikings, both of whom field teams in popular spectator sports including soccer, baseball, and basketball. Portland State also has a football team. Additionally, the University of Oregon Ducks and the Oregon State University Beavers both receive substantial attention and support from many Portland residents, despite their campuses being 110 and 84 miles from the city, respectively.[229]

Running is a popular activity in Portland, and every year the city hosts the Portland Marathon as well as parts of the Hood to Coast Relay, the world's largest long-distance relay race (by number of participants). Portland served as the center to an elite running group, the Nike Oregon Project until its 2019 disbandment following coach Alberto Salazar's ban due to doping violations [230] and is the residence of elite runners including American record holder at 10,000m Galen Rupp.[231]

Historic Erv Lind Stadium is located in Normandale Park.[232] It has been home to professional and college softball.

Portland also hosts numerous cycling events and has become an elite bicycle racing destination.[citation needed][233] The Oregon Bicycle Racing Association supports hundreds of official bicycling events every year. Weekly events at Alpenrose Velodrome and Portland International Raceway allow for racing nearly every night of the week from March through September. Cyclocross races, such as the Cross Crusade, can attract over 1,000 riders and spectators.[234]

On December 4, 2019, the Vancouver Riptide of the American Ultimate Disc League announced that they ceased team operations in Vancouver in 2017 and are moving down to Portland Oregon for the 2020 AUDL season.

| Club | Sport | Current League | Championships | Venue | Founded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portland Trail Blazers | Basketball | NBA | 1 (1977) | Moda Center | 1970 |

| Portland Thorns FC | Soccer | NWSL | 3 (2013, 2017, 2022) | Providence Park | 2012 |

| Portland Timbers | Soccer | MLS | 1 (2015) | Providence Park | 2009 |

| Portland Timbers 2 | Soccer | MLS Next Pro | 0 | Hillsboro Stadium | 2014 |

| Hillsboro Hops | Baseball | Northwest League | 3 (2014, 2015, 2019) | Ron Tonkin Field | 2013 |

| Portland Winterhawks | Hockey | WHL | 3 (1981–82, 1997–98, 2012–13) | Veterans Memorial Coliseum | 1976 |

Parks and recreation

Parks and greenspace planning date back to John Charles Olmsted's 1903 Report to the Portland Park Board. In 1995, voters in the Portland metropolitan region passed a regional bond measure to acquire valuable natural areas for fish, wildlife, and people.[235] Ten years later, more than 8,100 acres (33 km2) of ecologically valuable natural areas had been purchased and permanently protected from development.[236]

Portland is one of only four cities in the U.S. with extinct volcanoes within its boundaries (along with Pilot Butte in Bend, Oregon, Jackson Volcano in Jackson, Mississippi, and Diamond Head in Honolulu, Hawaii). Mount Tabor Park is known for its scenic views and historic reservoirs.[237]

Forest Park is the largest wilderness park within city limits in the United States, covering more than 5,000 acres (2,023 ha).[238] Portland is also home to Mill Ends Park, the world's smallest park (a two-foot-diameter circle, the park's area is only about 0.3 m2). Washington Park is just west of downtown and is home to the Oregon Zoo, Hoyt Arboretum, the Portland Japanese Garden, and the International Rose Test Garden. Portland is also home to Lan Su Chinese Garden (formerly the Portland Classical Chinese Garden), an authentic representation of a Suzhou-style walled garden. Portland's east side has several formal public gardens: the historic Peninsula Park Rose Garden, the rose gardens of Ladd's Addition, the Crystal Springs Rhododendron Garden, the Leach Botanical Garden, and The Grotto.

Portland's downtown features two groups of contiguous city blocks dedicated for park space: the North and South Park Blocks.[239][240] The 37-acre (15 ha) Tom McCall Waterfront Park was built in 1974 along the length of the downtown waterfront after Harbor Drive was removed; it now hosts large events throughout the year.[241] The nearby historically significant Burnside Skatepark and five indoor skateparks give Portland a reputation as possibly "the most skateboard-friendly town in America."[242]

Tryon Creek State Natural Area is one of three Oregon State Parks in Portland and the most popular; its creek has a run of steelhead. The other two State Parks are Willamette Stone State Heritage Site, in the West Hills, and the Government Island State Recreation Area in the Columbia River near Portland International Airport.

Portland's city park system has been proclaimed one of the best in America. In its 2013 ParkScore ranking, the Trust for Public Land reported Portland had the seventh-best park system among the 50 most populous U.S. cities.[243] In February 2015, the City Council approved a total ban on smoking in all city parks and natural areas and the ban has been in force since July 1, 2015. The ban includes cigarettes, vaping, as well as marijuana.[244]

Government

City hall

The city of Portland is governed by the Portland City Council, which includes a mayor, four commissioners, and an auditor. Each is elected citywide to serve a four-year term. Each commissioner oversees one or more bureaus responsible for the day-to-day operation of the city. The mayor serves as chairman of the council and is principally responsible for allocating department assignments to his fellow commissioners. The auditor provides checks and balances in the commission form of government and accountability for the use of public resources. In addition, the auditor provides access to information and reports on various matters of city government. Portland is the only large city left in the United States with the commission form of government.[245]

![Built in 1869, Pioneer Courthouse (pictured) is the oldest federal building in the Pacific Northwest[246]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7e/Pioneer_Courthouse%2C_Portland%2C_Oregon%2C_2013.jpeg/220px-Pioneer_Courthouse%2C_Portland%2C_Oregon%2C_2013.jpeg)

The city's Community & Civic Life (formerly Office of Neighborhood Involvement)[247] serves as a conduit between city government and Portland's 95 officially recognized neighborhoods. Each neighborhood is represented by a volunteer-based neighborhood association which serves as a liaison between residents of the neighborhood and the city government. The city provides funding to neighborhood associations through seven district coalitions, each of which is a geographical grouping of several neighborhood associations. Most (but not all) neighborhood associations belong to one of these district coalitions.

Portland and its surrounding metropolitan area are served by Metro, the United States' only directly elected metropolitan planning organization. Metro's charter gives it responsibility for land use and transportation planning, solid waste management, and map development. Metro also owns and operates the Oregon Convention Center, Oregon Zoo, Portland Center for the Performing Arts, and Portland Metropolitan Exposition Center.

The Multnomah County government provides many services to the Portland area, as do Washington and Clackamas counties to the west and south.

Fire and emergency services are provided by Portland Fire & Rescue.

On November 8, 2022, Portland residents approved a charter reform ballot measure to replace the commission form of government with a 12-member council elected in four districts using single transferable vote, with a professional city manager appointed by a directly-elected mayor. The city expects to hold the first election for this new system in 2024.[248]

Courts and law enforcement

Law enforcement is provided by the Portland Police Bureau, whose headquarters are located in the Justice center building, along with the county jail.

State and national politics

Portland strongly favors the Democratic Party. All city offices are non-partisan.[249] However, a Republican has not been elected as mayor since Fred L. Peterson in 1952, and has not served as mayor even on an interim basis since Connie McCready held the post from 1979 to 1980.

Portland's delegation to the Oregon Legislative Assembly is entirely Democratic. In the current 76th Oregon Legislative Assembly, which first convened in 2011, four state Senators represent Portland in the state Senate: Diane Rosenbaum (District 21), Chip Shields (District 22), Jackie Dingfelder (District 23), and Rod Monroe (District 24). Portland sends six Representatives to the state House of Representatives: Rob Nosse (District 42), Tawna Sanchez (District 43), Tina Kotek (District 44), Barbara Smith Warner (District 45), Alissa Keny-Guyer (District 46), and Diego Hernandez (District 47).

Portland is split among three U.S. congressional districts. Most of the city is in the 3rd District, represented by Earl Blumenauer, who served on the city council from 1986 until his election to Congress in 1996. Most of the city west of the Willamette River is part of the 1st District, represented by Suzanne Bonamici. A small portion of southwestern Portland is in the 5th District, represented by Kurt Schrader. All three are Democrats; a Republican has not represented a significant portion of Portland in the U.S. House of Representatives since 1975. Both of Oregon's senators, Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, are from Portland and are also both Democrats.

In the 2008 presidential election, Democratic candidate Barack Obama easily carried Portland, winning 245,464 votes from city residents to 50,614 for his Republican rival, John McCain. In the 2012 presidential election, Democratic candidate Barack Obama again easily carried Portland, winning 256,925 votes from Multnomah county residents to 70,958 for his Republican rival, Mitt Romney.[250]

Sam Adams, the former mayor of Portland, became the city's first openly gay mayor in 2009.[251] In 2004, 59.7 percent of Multnomah County voters cast ballots against Oregon Ballot Measure 36, which amended the Oregon Constitution to prohibit recognition of same-sex marriages. The measure passed with 56.6% of the statewide vote. Multnomah County is one of two counties where a majority voted against the initiative; the other is Benton County, which includes Corvallis, home of Oregon State University.[252] On April 28, 2005, Portland became the only city in the nation to withdraw from a Joint Terrorism Task Force.[253][254] As of February 19, 2015, the Portland city council approved permanently staffing the JTTF with two of its city's police officers.[255]

| Voter registration and party enrollment As of December 2015[update][256] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 197,133 | 54.0% | |||

| Republican | 40,374 | 11.1% | |||

| Unaffiliated | 95,561 | 26.2% | |||

| Libertarian | 2,752 | 0.8% | |||

| Other | 31,804 | 8.7% | |||

| Total | 364,872 | 100% | |||

City planning and development

The city consulted with urban planners as far back as 1904, resulting in the development of Washington Park and the 40-Mile Loop greenway, which connects many of the city's parks.[257] Portland is often cited as an example of a city with strong land use planning controls.[258] This is largely the result of statewide land conservation policies adopted in 1973 under Governor Tom McCall, in particular the requirement for an urban growth boundary (UGB) for every city and metropolitan area. The opposite extreme, a city with few or no controls, is typically illustrated by Houston.[259][260][261][262]

Oregon's 1973 "urban growth boundary" law limits the boundaries for large-scale development in each metropolitan area in Oregon.[263] This limits access to utilities such as sewage, water and telecommunications, as well as coverage by fire, police and schools.[263] Portland's urban growth boundary, adopted in 1979, separates urban areas (where high-density development is encouraged and focused) from traditional farm land (where restrictions on non-agricultural development are very strict).[264] This was atypical in an era when automobile use led many areas to neglect their core cities in favor of development along interstate highways, in suburbs, and satellite cities.

The original state rules included a provision for expanding urban growth boundaries, but critics felt this wasn't being accomplished. In 1995, the State passed a law requiring cities to expand UGBs to provide enough undeveloped land for a 20-year supply of future housing at projected growth levels.[265] In 2007, the legislature changed the law to require the maintenance of an estimated 50 years of growth within the boundary, as well as the protection of accompanying farm and rural lands.[142] The growth boundary, along with efforts of the Portland Development Commission to create economic development zones, has led to the development of a large portion of downtown, a large number of mid- and high-rise developments, and an overall increase in housing and business density.[266]

Prosper Portland (formerly the Portland Development Commission) is a semi-public agency that plays a major role in downtown development; city voters created it in 1958 to serve as the city's urban renewal agency. It provides housing and economic development programs within the city and works behind the scenes with major local developers to create large projects. In the early 1960s, the Portland Development Commission led the razing of a large Italian-Jewish neighborhood downtown, bounded roughly by I-405, the Willamette River, 4th Avenue and Market street.[267] Mayor Neil Goldschmidt took office in 1972 as a proponent of bringing housing and the associated vitality back to the downtown area, which was seen as emptying out after 5 pm. The effort has had dramatic effects in the 30 years since, with many thousands of new housing units clustered in three areas: north of Portland State University (between I-405, SW Broadway, and SW Taylor St.); the RiverPlace development along the waterfront under the Marquam (I-5) bridge; and most notably in the Pearl District (between I-405, Burnside St., NW Northrup St., and NW 9th Ave.).

![The 2015-opened Tilikum Crossing attracted national attention for being a major bridge open only to transit vehicles, cyclists and pedestrians, and not private motor vehicles.[268][269]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/24/Tilikum_Crossing_with_streetcar_and_MAX_train_in_2016.jpg/200px-Tilikum_Crossing_with_streetcar_and_MAX_train_in_2016.jpg)

Historically, environmental consciousness has weighed significantly in the city's planning and development efforts.[270] Portland was one of the first cities in the United States to promote and integrate alternative forms of transportation, such as the MAX Light Rail and extensive bike paths.[270] The Urban Greenspaces Institute, housed in Portland State University Geography Department's Center for Mapping Research, promotes better integration of the built and natural environments. The institute works on urban park, trail, and natural areas planning issues, both at the local and regional levels.[271] In October 2009, the Portland City Council unanimously adopted a climate action plan that will cut the city's greenhouse gas emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050.[272] The city's longstanding efforts were recognized in a 2010 Reuters report, which named Portland the second-most environmentally conscious or "green" city in the world after Reykjavík, Iceland.[270] A recent study showed that green infrastructure is now distributed more equitably for stormwater management.[273]

As of 2012, Portland was the largest city in the United States that did not add fluoride to its public water supply,[274] and fluoridation has historically been a subject of controversy in the city.[275] Portland voters have four times voted against fluoridation, in 1956, 1962, 1980 (repealing a 1978 vote in favor), and 2013.[276] In 2012 the city council, responding to advocacy from public health organizations and others, voted unanimously to begin fluoridation by 2014. Fluoridation opponents forced a public vote on the issue,[277] and on May 21, 2013, city voters again rejected fluoridation.[278]

Education

Primary and secondary education