world.wikisort.org - USA

Lowell (/ˈloʊəl/) is a city in Massachusetts, in the United States. Alongside Cambridge, It is one of two traditional seats of Middlesex County. With an estimated population of 115,554 in 2020,[3] it was the fifth most populous city in Massachusetts as of the last census, and the third most populous in the Boston metropolitan statistical area.[4] The city also is part of a smaller Massachusetts statistical area, called Greater Lowell, and of New England's Merrimack Valley region.

Lowell, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of Lowell | |

|

Left-right from top: Lowell City Hall, Lowell mills, University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell Skyline | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Mill City, Spindle City, City of Lights City of Magic | |

| Motto: "Art is the Handmaid of Human Good."[1] | |

Location in Middlesex County in Massachusetts | |

Lowell Location in the United States  Lowell Lowell (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 42°38′22″N 71°18′53″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Middlesex |

| Region | New England |

| Settled | 1652 |

| Incorporated | 1826 |

| A city | 1836 |

| Named for | Francis Cabot Lowell |

| Government | |

| • Type | Manager-City council |

| • Mayor | Sokhary Chau |

| • City Manager | Thomas Golden Jr. |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14.53 sq mi (37.63 km2) |

| • Land | 13.61 sq mi (35.25 km2) |

| • Water | 0.92 sq mi (2.38 km2) |

| Elevation | 102 ft (31 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 115,554 |

| • Density | 8,489.75/sq mi (3,278.02/km2) |

| • Demonym | Lowellian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 01850, 01851, 01852, 01853, 01854 |

| Area code | 978 / 351 |

| FIPS code | 25-37000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0611832 |

| Website | City of Lowell, Massachusetts |

Flag of Lowell | |

| Mill Mayor flag | |

| Adopted | 1986 |

|---|---|

| Relinquished | 5 December 2001 (Readopted in 2009) |

| Design | City seal behind a White Background |

| Designed by | William Ckrocker |

Incorporated in 1826 to serve as a mill town, Lowell was named after Francis Cabot Lowell, a local figure in the Industrial Revolution. The city became known as the cradle of the American Industrial Revolution because of its textile mills and factories. Many of Lowell's historic manufacturing sites were later preserved by the National Park Service to create Lowell National Historical Park.[5] During the Cambodian genocide (1975–1979), the city took in an influx of refugees, leading to a Cambodia Town and America's second largest Cambodian-American population.[6]

Lowell is home to two institutions of higher education. UMass Lowell, part of the University of Massachusetts system, has three campuses in the city. Middlesex Community College's two campuses are in Lowell and in the town of Bedford, Massachusetts. Arts facilities in the city include the Whistler House Museum of Art, the Merrimack Repertory Theatre, the Lowell Memorial Auditorium, and Sampas Pavilion. In sports, the city has a long tradition of boxing, hosting the annual New England Golden Gloves boxing tournament. The city has a baseball stadium, Edward A. LeLacheur Park, and a multipurpose indoor sports arena, the Tsongas Center, both of which have hosted collegiate and minor-league professional sports teams.

History

Founded in the 1820s as a planned manufacturing center for textiles, Lowell is located along the rapids of the Merrimack River, 25 mi (40 km) northwest of Boston in what was once the farming community of East Chelmsford, Massachusetts. The so-called Boston Associates, including Nathan Appleton and Patrick Tracy Jackson of the Boston Manufacturing Company, named the new mill town after their visionary leader, Francis Cabot Lowell,[7] who had died five years before its 1823 incorporation. As Lowell's population grew, it acquired land from neighboring towns, and diversified into a full-fledged urban center. Many of the men who composed the labor force for constructing the canals and factories had immigrated from Ireland, escaping the poverty and Great Famine of the 1830s and 1840s. The mill workers, young single women called Mill Girls, generally came from the farm families of New England.

By the 1850s, Lowell had the largest industrial complex in the United States. The textile industry wove cotton produced in the Southern United States. In 1860, there were more cotton spindles in Lowell than in all eleven states combined that would form the Confederate States of America.[8] Many of the coarse cottons produced in Lowell eventually returned to the South to clothe enslaved people, and, according to historian Sven Beckert, "'Lowell' became the generic term slaves used to describe coarse cottons."[9] The city continued to thrive as a major industrial center during the 19th century, attracting more migrant workers and immigrants to its mills. Next were the Catholic Germans, followed by a large influx of French Canadians during the 1870s and 1880s. Later waves of immigrants came to work in Lowell and settled in ethnic neighborhoods, with the city's population reaching almost 50% foreign-born by 1900.[10] By the time World War I broke out in Europe, the city had reached its economic peak.

The Mill Cities' manufacturing base declined as companies began to relocate to the South in the 1920s.[10] The city fell into hard times, and was even referred to as a "depressed industrial desert" by Harper's Magazine in 1931, as the Great Depression worsened. At this time, more than one third of its population was "on relief" (government assistance), as only three of its major textile corporations remained active.[10] Several years later, the mills were reactivated, making parachutes and other military necessities for World War II. However, this economic boost was short-lived and the post-war years saw the last textile plants close.

Zoning, development and the Massachusetts Miracle

In the 1970s, Lowell became part of the Massachusetts Miracle, being the headquarters of Wang Laboratories. At the same time, Lowell became home to thousands of new immigrants, many from Cambodia, following the genocide at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. The city continued to rebound, but this time, focusing more on culture. The former mill district along the river was partially restored and became part of the Lowell National Historical Park, founded in the late 1970s.

Although Wang went bankrupt in 1992, the city continued its cultural focus by hosting the nation's largest free folk festival, the Lowell Folk Festival, as well as many other cultural events. This effort began to attract other companies and families back to the urban center. Additional historic manufacturing and commercial buildings were adapted as residential units and office space. By the 1990s, Lowell had built a new ballpark and arena, which became home to two minor league sports teams, the Lowell Devils and Lowell Spinners. The city also began to have a larger student population. The University of Massachusetts Lowell and Middlesex Community College expanded their programs and enrollment. During the period of time when Lowell was part of the Massachusetts Miracle, the Lowell City Development Authority created a Comprehensive Master Plan which included recommendations for zoning adaptations within the city. The city's original zoning code was adopted in 1926 and was significantly revised in 1966 and 2004, with changes included to respond to concerns about overdevelopment.[11]

In 2002, in lieu of updating the Comprehensive Master Plan, more broad changes were recommended so that the land use and development would be consistent with the current master plan. The most significant revision to the 1966 zoning code is the adoption of an inclusion of a transect-based zoning code and some aspects of a form-based code style of zoning that emphasizes urban design elements as a means to ensure that infill development will respect the character of the neighborhood or district in question. By 2004, the recommended zoning changes were unanimously adopted by the City Council and despite numerous changes to the 2004 Zoning Code, it remains the basic framework for resolving zoning issues in Lowell to this day.[12]

The Hamilton Canal District (HCD) is the first district in Lowell in which regulation and development is defined by Form-Based Code (HCD-FBC) and legislated by its own guiding framework consistent to the HCD Master Plan.[13] The HCD is a major redevelopment project that comprises 13-acres of vacant, underutilized land in downtown Lowell abutting former industrial mills. Trinity Financial was elected as the Master Developer to recreate this district with a vision of making a mixed-use neighborhood. Development plans included establishing the HCD as a gateway to downtown Lowell and enhanced connectivity to Gallagher Terminal.[14][15]

Anti-crime efforts

In the 1990s, Lowell had been locally notorious for being a place of high drug trafficking and gang activity, and was the setting for a real life documentary, High on Crack Street: Lost Lives in Lowell. In the years from 1994 to 1999, crime dropped 50 percent, the highest rate of decrease for any city in America with over 100,000 residents.

Within one generation, by 2009, Lowell was ranked as the 139th most dangerous city of over 75,000 residents in the United States, out of 393 communities. Out of Massachusetts cities, nine are larger than 75,000 residents, and Lowell was fifth.[16] For comparison Lowell was still rated safer than Boston (104 of 393), Providence, RI (123), Springfield (51), Lynn (120), Fall River (103), and New Bedford (85), but rated more dangerous than Cambridge (303), Newton (388), Quincy (312), and Worcester (175).[16]

Geography

Lowell is located at 42°38′22″N 71°18′53″W (42.639444, −71.314722).[17] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 14.5 square miles (38 km2) of which 13.8 square miles (36 km2) is land and 0.8 square miles (2.1 km2) (5.23%) is water.

Climate

Lowell features a four-season Humid continental climate, with long and very cold winters, which typically experience an average 56 in (1,400 mm) of snowfall, with the highest ever recorded seasonal snowfall being 120 in (3,000 mm) in the winter of 2014–2015. Summers are hot and humid, and of average length, with autumn and spring are brief transition periods between the two. On average, temperature in Lowell ranges from 64 to 84 °F (18 to 29 °C) in the summer months, and between 2 and 33 °F (−17 and 1 °C) in the winter months, with the yearly average being 49 °F (9 °C).

| Climate data for Lowell, Massachusetts (1991–2020 normals; extremes Aug 1, 1885-present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 70 (21) |

77 (25) |

89 (32) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

103 (39) |

100 (38) |

89 (32) |

81 (27) |

76 (24) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 56 (13) |

58 (14) |

68 (20) |

83 (28) |

90 (32) |

94 (34) |

96 (36) |

94 (34) |

90 (32) |

80 (27) |

70 (21) |

60 (16) |

98 (37) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 34.0 (1.1) |

37.3 (2.9) |

45.4 (7.4) |

59.0 (15.0) |

70.0 (21.1) |

79.0 (26.1) |

84.7 (29.3) |

83.0 (28.3) |

75.5 (24.2) |

62.4 (16.9) |

50.5 (10.3) |

39.8 (4.3) |

60.0 (15.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 24.9 (−3.9) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

34.9 (1.6) |

46.8 (8.2) |

57.5 (14.2) |

67.0 (19.4) |

72.8 (22.7) |

71.1 (21.7) |

63.5 (17.5) |

50.9 (10.5) |

40.4 (4.7) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

49.0 (9.4) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 15.8 (−9.0) |

16.9 (−8.4) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

34.6 (1.4) |

45.0 (7.2) |

55.0 (12.8) |

60.9 (16.1) |

59.3 (15.2) |

51.5 (10.8) |

39.5 (4.2) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

22.1 (−5.5) |

37.9 (3.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

1 (−17) |

8 (−13) |

24 (−4) |

33 (1) |

43 (6) |

52 (11) |

50 (10) |

38 (3) |

27 (−3) |

17 (−8) |

6 (−14) |

−5 (−21) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−29 (−34) |

−14 (−26) |

6 (−14) |

27 (−3) |

33 (1) |

44 (7) |

38 (3) |

26 (−3) |

19 (−7) |

1 (−17) |

−20 (−29) |

−29 (−34) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.61 (92) |

3.20 (81) |

4.32 (110) |

4.06 (103) |

3.81 (97) |

4.37 (111) |

3.86 (98) |

4.00 (102) |

3.89 (99) |

5.00 (127) |

3.85 (98) |

4.54 (115) |

48.51 (1,233) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 15.9 (40) |

14.2 (36) |

11.2 (28) |

1.9 (4.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1.5 (3.8) |

11.4 (29) |

56.1 (141.6) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 11 (28) |

11 (28) |

10 (25) |

1 (2.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (2.5) |

8 (20) |

17 (43) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 128 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 21 |

| Source: NOAA[18] | |||||||||||||

Physical

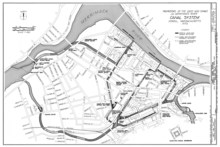

Lowell is located at the confluence of the Merrimack and Concord rivers. The Pawtucket Falls, a mile-long set of rapids with a total drop in elevation of 32 feet, ends where the two rivers meet. At the top of the falls is the Pawtucket Dam, designed to turn the upper Merrimack into a millpond, diverted through Lowell's extensive canal system.

The Merrimack, which flows southerly from Franklin, New Hampshire to Lowell, makes a northeasterly turn there before emptying into the Atlantic Ocean at Newburyport, Massachusetts, approximately 40 mi (64 km) downriver from Lowell. It is believed that in prior ages, the Merrimack continued south from Lowell to empty into the ocean somewhere near Boston. The glacial deposits that redirected the flow of the river left the drumlins that dot the city, most notably, Fort Hill in the Belvidere neighborhood. Other large hills in Lowell include Lynde Hill, also in Belvidere, and Christian Hill, in the easternmost part of Centralville at the Dracut town line.

The Concord, or Musketaquid (its original name), forms from the confluence of the Assabet and Sudbury rivers at Concord, Massachusetts. This river flows north into the city, and the area around the confluence with the Merrimack was known as Wamesit. Like the Merrimack, the Concord, although a much smaller river, has many waterfalls and rapids that served as power sources for early industrial purposes, some well before the founding of Lowell. Immediately after the Concord joins the Merrimack, the Merrimack descends another ten feet in Hunt's Falls.

There is an ninety-degree bend in the Merrimack partway down the Pawtucket Falls. At this point, the river briefly widens and shallows. Here, Beaver Brook enters from the north, separating the city's two northern neighborhoods, Pawtucketville and Centralville. Entering the Concord River from the southwest is River Meadow, or Hale's Brook. This brook flows largely in a man-made channel, as the Lowell Connector was built along it. Both of these minor streams have limited industrial histories as well.

The bordering towns (clockwise from north) are Dracut, Tewksbury, Billerica, Chelmsford, and Tyngsborough. The border with Billerica is a point in the middle[citation needed] of the Concord River where Lowell and Billerica meet Tewksbury and Chelmsford.

The ten communities designated part of the Lowell Metropolitan area by the 2000 US Census are Billerica, Chelmsford, Dracut, Dunstable, Groton, Lowell, Pepperell, Tewksbury, Tyngsborough, and Westford, and Pelham, New Hampshire. See Greater Lowell.

Neighborhoods

Lowell has eight distinct neighborhoods: the Acre, Back Central, Belvidere, Centralville, Downtown, Highlands, Pawtucketville, and South Lowell.[19] The city also has five ZIP codes: four are geographically distinct general ZIP codes, and one (01853) is for post-office boxes only.

The Centralville neighborhood, ZIP Code 01850, is the northeastern section of the city, north of the Merrimack River and east of Beaver Brook. Christian Hill is the section of Centralville east of Bridge Street.

The Highlands, ZIP Code 01851, is the most populated neighborhood, with almost a quarter of the city residing here. It is located in the southwestern section of the city, bordered to the east by the Lowell Connector and to the north by the railroad. Lowellians further distinguish the sections of the Highlands as the Upper Highlands and the Lower Highlands, the latter being the area closer to downtown. Middlesex Village, Tyler Park, and Drum Hill are in this ZIP Code. The Upper Highlands also includes the University of Massachusetts Lowell, South Campus (Fine Arts, Humanities, Social Sciences, Health Sciences & Education).

Downtown, Belvidere, Back Central, and South Lowell make up the 01852 ZIP Code, and are the southeastern sections of the city (south of the Merrimack River and southeast of the Lowell Connector). Belvidere is the mostly residential area south of the Merrimack River, east of the Concord River, and north of the Lowell and Lawrence railroad. Belvidere Hill Historic District runs along Fairmount Street. Lower Belvidere is the section west of Nesmith Street. Rogers Fort Hill Park Historic District, Lowell Cemetery, and Shedd Park are this side of town. Back Central is an urban area south of downtown, toward the mouth of River Meadow Brook. South Lowell is the area south of the railroad and east of the Concord River. Other minor neighborhoods within this ZIP Code are Ayers City, Bleachery, Chapel Hill, the Grove, Oaklands, Riverside Park, Swede Village, and Wigginville. Although the use of the names of these smaller neighborhoods has been in decline in the past decades, there has been recently a reemergence of their use. Downtown Lowell includes the UMass Lowell East Campus which consists of university housing, recreation facilities, research and the university's sports arena, as well as the Middlesex Community College.

Pawtucketville, the University of Massachusetts Lowell, North Campus; and the Acre make up the 01854 ZIP Code. The northwestern portion of the city includes the neighborhood where Jack Kerouac resided around the area of University Avenue (previously known as Moody Street). The North Campus of UMass Lowell (Colleges of Engineering, Sciences and Business) is in Pawtucketville near the Lowell General Hospital. The older parts of the neighborhood are around University Avenue and Mammoth Road, whereas the newer parts are around Varnum Avenue. Pawtucketville is the official entrance to the Lowell-Dracut-Tyngsborough State Forest, the site of an historic Native American tribe, and in the age of the Industrial Revolution was a prominent source of granite used in canals and factory foundations.[20]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 6,474 | — |

| 1840 | 20,796 | +221.2% |

| 1850 | 33,383 | +60.5% |

| 1860 | 36,827 | +10.3% |

| 1870 | 40,928 | +11.1% |

| 1880 | 59,475 | +45.3% |

| 1890 | 77,696 | +30.6% |

| 1900 | 94,969 | +22.2% |

| 1910 | 106,294 | +11.9% |

| 1920 | 112,759 | +6.1% |

| 1930 | 100,234 | −11.1% |

| 1940 | 101,389 | +1.2% |

| 1950 | 97,249 | −4.1% |

| 1960 | 92,107 | −5.3% |

| 1970 | 94,239 | +2.3% |

| 1980 | 92,418 | −1.9% |

| 1990 | 103,439 | +11.9% |

| 2000 | 105,167 | +1.7% |

| 2010 | 106,519 | +1.3% |

| 2020 | 115,554 | +8.5% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[32] | ||

Population Density: According to the 2010 Census,[33] there were 106,519 people living in the city. The population density was 7,842.1 inhabitants per square mile (3,027.9/km2). There were 41,431 housing units at an average density of 2,865.5/sq mi (1,106.4/km2).

Household Size: 2010, there were 38,470 households, and 23,707 families living in Lowell; the average household size was 2.66 and the average family size was 3.31. Of those households, 34.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.9% were married couples living together, 14.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 38.4% were non-families, 29.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older.[33]

Age Distributions: Lowell has also experienced a significant increase in the number of residents between the ages of 50-69 while the percentages of residents under the age of 15 and over the age of 70 decreased.[34] In 2010 the city's population had a median age of 32.6.[35] The age distribution was 23.7% of the population under the age of 18, 13.5% from 18 to 24, 29.4% from 25 to 44, 23.3% from 45 to 64, and 10.1% who were 65 years of age or older. For every 100 females, there were 98.6 males; while for every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 97.6 males.[35]

Median Income: for a household in the city was $51,714, according to the American Community Survey 5-year estimate ending in 2012.[36] The median income for a family was $55,852. Males had a median income of $44,739 versus $35,472 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,730. About 15.2% of families and 17.5% of individuals were below the poverty line, including 24.5% of those under age 18 and 13.2% of those age 65 or over.[37]

Racial Makeup: In 2010, the ethnic diversity of the city was 60.3% White (49.3% Non-Hispanic White[38]), 20.2% Asian American (12.5% Cambodian, 2.0% Indian, 1.7% Vietnamese, 1.4% Laotian), 6.8% African American, 0.3% Native American, 8.8% from other races, 3.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 17.3% of the population. The largest Hispanic group was those of Puerto Rican ancestry, comprising 11.3% of the population.

African Immigrants: In 2010 there were about 6,000 people of recent African heritage living in Lowell making up nearly the entire African American population of the city.[39]

Cambodian-American Population: In 2010, Lowell had the highest proportion of residents of Cambodian origin of any place in the United States, at 12.5% of the population. The Government of Cambodia opened up its third U.S. Consular Office in Lowell, on April 27, 2009, with Sovann Ou as current advisor to the Cambodian Embassy.[40] The other consular offices are in Long Beach, California, and Seattle, Washington, which also have large Cambodian communities.

Crime data

According to current FBI Crime Data Analysis, Lowell is the 46th most dangerous city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, for all sizes,[41] the violent crime rate for Lowell was less than half of the violent crime rate in Boston, with no murders compared to 49 in Boston. Lowell's crime rate has dropped tremendously since the 1990s, and while the likelihood of becoming a victim of violent crime in Massachusetts are 1 in 265, the odds in Lowell are 1 in 289, making Lowell (approximately) 10% safer than the rest of the state, on average.[42] Lowell's violent crime rate is comparable to Honolulu, HI and is less than one-quarter that of Washington, D.C.[43]

Arts and culture

Annual events

- February: Winterfest – celebration of winter. (Also, Lowell's Birthday)

- March: Lowell Women's Week[44] – A week of events recognizing women's achievements, struggles, and contributions to the Lowell community past and present. Irish Cultural Week - A celebration of Irish history and hulture within the Greater Lowell community.

- April: Lowell Film Festival[45] – Showcases documentary and feature-length films focusing on a variety of topics of interest to the Greater Lowell community and beyond

- May: Doors Open Lowell[46] – A celebration of preservation, architecture, and design where many historic buildings that normally have limited public access are open for viewing

- June: African Festival[47] – A celebration of the various African communities in and around Lowell

- July: Lowell Folk Festival – A three-day free folk music and traditional arts festival attended by on average 250,000 people on the last weekend in July

- August: Lowell Southeast Asian Water Festival[48] – celebrates Southeast Asian culture

- September: Lowell Kinetic Sculpture Race[49] – From the crossroads of Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Mathematics comes a spectacular racing spectacle!

- October: Lowell Celebrates Kerouac Festival[50] – A celebration of the works of Jack Kerouac and his roots in the city of Lowell

- October: Bay State Marathon and half marathon

Points of interest

Among the many tourist attractions, Lowell also currently has 39 places on the National Register of Historic Places including many buildings and structures as part of the Lowell National Historical Park.

- In the mid-1980s, Kerouac Park was placed in downtown.[51]

- Lowell National Historical Park: Maintains Lowell's history as an early manufacturing and immigrant city. Exhibits include weave rooms, a waterpower exhibit, and paths along 5.6 mi (9.0 km) of largely restored canals.

- Lowell-Dracut-Tyngsboro State Forest: Hiking, biking, and cross-country skiing trails in an urban state forest

- University of Massachusetts Lowell: State University

- University of Massachusetts Lowell Radiation Laboratory: The site of a small nuclear reactor at the school

- Vandenberg Esplanade: Walking, biking, swimming, and picnicking park along the banks of the Merrimack River. Contains the Sampas Pavilion.

- Western Avenue Studios:[52] Largest complex of artists studios in the United States at 122 Western Avenue.

- Jack Kerouac's birthplace: In the Centralville section of the city at 9 Lupine Road.

- Armenian genocide memorial: "A Mother's Hands" monument at Lowell City Hall.

- Bette Davis's birthplace: In the Highlands section of the city at 22 Chester Street.

- Rosalind Elias's birthplace: In the Acre neighborhood at 144 School Street .

- Lowell Cemetery: burial site of many of Lowell's wealthy industrialists from the Victorian era, as well as several U.S. Congressmen, a Massachusetts Governor, John McFarland, and a U.S. Senator. 77 Knapp Avenue.

- Edson Cemetery: burial site of Jack Kerouac and William Preston Phelps. Location of a monument dedicated to Chief Passaconaway. 1375 Gorham Street.

- The Acre: Lowell's gateway neighborhood where waves of immigrants have established their communities.

- Yorick Building: Former home of the gentlemen's club the "Yorick Club", currently a restaurant & function facility (Cobblestones).

- Little Cambodia: In 2010, the city began an effort to make it a tourist destination.[53]

Culture

In the early years of the 1840s when the population quickly exceeded 20,000, Lowell became very active as a cultural center, with the construction of the Lowell Museum, the Mechanics Hall, as well as the new City Hall used for art exhibits, lectures, and for the performing arts. The Lowell Museum was lost in a devastating fire in the early morning of January 31, 1856,[54] but was quickly rehoused in a new location. The Lowell Art Association was founded in 1876, and the new Opera House was built in 1889.[55] Continuing to inspire and entertain, Lowell currently has a plethora of artistic exhibitions and performances throughout a wide range of venues in the city:

Museums and public galleries

- 119 Gallery[56]

- Arts League of Lowell & All Gallery[57]

- The American Textile History Museum (closed in 2016)[58]

- Ayer Lofts[59] Artist Live-work Lofts

- The Boott Cotton Mills Museum: Lowell National Historic Park

- Brush Art Gallery and Studios[60]

- Gallery Z & Artist Cooperative[61]

- The Lowell Gallery[62]

- Mill No. 5 – an eclectic indoor mall/streetscape featuring artisanal foods and hand-made items, live music and The Luna Theater, an independent film venue.[63]

- National Streetcar Museum[64]

- The New England Quilt Museum[65]

- Patrick J. Mogan Cultural Center: Lowell National Historic Park

- Whistler House Museum of Art – Art museum in birthplace of James McNeill Whistler.

- Western Avenue Studios (The Loading Dock Galleries)[66] – A converted mill with over 300 working artists and musicians.

- UMass Lowell Galleries[67]

Interactive and live performances

- Angkor Dance Troupe[68] – Cambodian classical and folk dance company and youth program[69]

- Arts League of Lowell[70]

- Center for Lowell History, University of Massachusetts Lowell[71] – local history library and archive

- The Gentlemen Songsters[72] The Lowell Chapter of The Barbershop Harmony Society – Causing Harmony In The Merrimack Valley.

- The Hi Hat – acoustic performance stage located at Mill No. 5.

- The Luna Theater – Independent film theater opened in 2014 and located inside Mill No. 5.

- Lowell Memorial Auditorium – Mid-sized venue for live performances.

- The Lowell Chamber Orchestra[73] – First professional orchestra based in Lowell

- Lowell Philharmonic Orchestra[74] – Community orchestra presenting free concerts and offering youth programs

- Lowell Poetry Network[75] – A network of area poets and appreciators of poetry who host readings, receptions, and open mics.

- Lowell Rocks[76] – Lowell nightlife and entertainment web site promoting performances at local bars and clubs

- Lowell Summer Music Series[77] – Boarding House Park

- Merrimack Repertory Theater – Professional equity theater

- Play by Player's Theatre Company – critically acclaimed community theater

- RRRecords – Internationally known record label and store

- Sampas Pavilion – Outdoor amphitheater on the banks of the Merrimack River

- Standing Room Only Players – musical review troupe

- UMass Lowell Department of Music Performances[78]

- The United Teen Equality Center[79] A by teens, for teens youth center promoting peace, positivity and empowerment for young people in Lowell.

- UnchARTed[80] – Gallery, studios, cafe, bar, and performance space in downtown Lowell

Libraries

Municipal

Pollard Memorial Library / Lowell City Library

The first Lowell public library was established in 1844 with 3,500 volumes, and was set up in the first floor of the Old City Hall, 226 Merrimack St. In 1872, the expanding collection was relocated down the street to the Hosford Building[81] at 134 Merrimack St. In 1890–1891, the City of Lowell hired local Architect Frederick W. Stickney to design the new Lowell City Library, known as "Memorial Hall, in honor of the city's men who died in the American Civil War.[82] In 1981, the library was renamed the Pollard Memorial Library in memory of the late Mayor Samuel S. Pollard. And, in the mid-2000s the century-old National Historic building underwent a major $8.5m renovation.[83] The city also expanded the library system to include the Senior Center Branch, located in the City of Lowell Senior Center.[84]

In fiscal year 2008, the city of Lowell spent 0.36% ($975,845) of its budget on its public libraries, which houses 236,000 volumes, and is a part of the Merrimack Valley Library Consortium. Currently, circulation of materials averages around 250,000 annually, with approximately one-third deriving from the children's collection.[82][85] In fiscal year 2009, Lowell spent 0.35% ($885,377) of its budget on the library—approximately $8 per person, per year ($9.83 adjusted for inflation in 2021).[86]

As of 2012, the Pollard Library purchases access for its patrons to databases owned by: EBSCO Industries; Gale, of Cengage Learning; Heritage Archives, Inc.; New England Historic Genealogical Society; OverDrive, Inc.; ProQuest; and World Trade Press.[87]

University

Lydon Library

The Lydon Library is a part of the University of Massachusetts Lowell system, and is located on the North Campus. The building is named in honor of President Martin J. Lydon, whose vision expanded and renamed the college during his tenure in the 1950s and 1960s.[88] Its current collection concentrates on the sciences, engineering, business management, social sciences, humanities, and health.[89]

O'Leary Library

The O'Leary Library is a part of the University of Massachusetts Lowell system, and is located on the South Campus. The building is named in honor of former History Professor and then President O'Leary, whose vision helped merge the Lowell colleges during his tenure in the 1970s and 1980s.[90] Its current collection concentrates on music and art.[91]

Center for Lowell History

The Center for Lowell History [special collections and archives] is a part of the University of Massachusetts Lowell system, established in 1971 to assure the safekeeping, preservation, and availability for study and research of materials in unique subject areas, particularly those related to the Greater Lowell Area and the University of Massachusetts Lowell. Located downtown in the Patrick J. Mogan Cultural Center at 40 French Street, the center is committed to the design and implementation of historical, educational, and cultural programs that link the university and the community in developing an economically strong and multi-culturally rich region. Its current collections and archives focus on historic and contemporary issues of Lowell (including: industrialization, textile technology, immigration, social history, regional history, labor history, women's history, and environmental history).[92]

Sports

Boxing

Boxing has formed an important part of Lowell's working-class culture. The city's auditorium hosts the annual New England Golden Gloves tournament, which featured fighters such as Rocky Marciano, Sugar Ray Leonard, and Marvin Hagler. Micky Ward and Dicky Eklund both began their careers in Lowell, the subject of the 2010 film The Fighter.[93] Arthur Ramalho's West End Gym is where many of the city's boxers train.[94]

Teams

- University of Massachusetts Lowell River Hawks, NCAA Division I Hockey, Soccer, Basketball, Baseball, Softball, Track & Field, Field Hockey, Volleyball

- Lowell Spinners – Former Class A short-season professional baseball affiliate of the Boston Red Sox

- Lowell All-Americans – NECBL (Collegiate Summer Baseball)

- New England Riptide – National Pro Fastpitch League (Major League Softball)

- Lowell Nor'easter[95] – Semi-Professional football team (New England Football League)

- Greater Lowell United FC – Semi-Pro soccer team (NPSL)[96][97]

Parks and recreation

Athletic venues

- Edward A. LeLacheur Park Baseball Stadium – owned by the University of Massachusetts Lowell

- Lowell Memorial Auditorium – performance and boxing venue.

- Tsongas Center at UMass Lowell – multi-use sports and concert venue (6500 seats hockey, 7800 concerts)- the University of Massachusetts Lowell River Hawks, and various arena shows. On April 1, 2006, the arena held the 2006 World Curling Championships.

- Cawley Memorial Stadium – Stadium for Lowell High School and other sporting events around the Merrimack Valley. Uses FieldTurf. Former home of the MICCA Marching Band Championship Finals

- Stoklosa Alumni Field – Baseball stadium, used by Lowell All-Americans (4,000 seats)

- Costello Athletic Center indoor arena on campus of the University of Massachusetts Lowell

- UMass Lowell Bellgarde Boathouse[98] used as a rowing and kayaking center for UMass Lowell and the greater Lowell area

- Long Meadow Golf Club[99] – Private 9 hole Golf course in the Belvidere neighborhood

- Mount Pleasant Golf Club[100] – Private 9 hole Golf course in the Highlands neighborhood

Government

| Lowell City Council (as of 1/3/22)[101] |

|---|

* =current mayor **=former mayor |

Lowell has a Plan-E council-manager government.[102] There are eleven city councilors and six school committee members, all elected by plurality-at-large in a non-partisan election. In 1957, Lowell voters repealed a single-transferable-vote system, which had been in place since 1943.[103]

The City Council chooses one of its members as mayor, and another as vice-mayor. The role of the mayor is ceremonial, but s/he runs the weekly meetings under the guidance of the City Clerk. In addition, the mayor serves as the Chairperson of the School Committee.

The administrative head of the city government is the City Manager, who is responsible for all day-to-day operations, functioning within the guidelines of City Council policy, and is hired by and serves indefinitely at the pleasure of at least 5 of 9 City Councilors. As of April 2017, the City Manager is Eileen M. Donghue replacing Kevin J. Murphy.[104][105]

Lowell is represented in the Massachusetts General Court by elected state representatives Thomas Golden, Jr. (D- 16th Middlesex), Vanna Howard[106] (D- 17th Middlesex), Rady Mom (D- 18th Middlesex),[107] and by State Senator Edward J. Kennedy (1st Middlesex) who is also a City Councilor.

Federally, the city is part of Massachusetts's 3rd congressional district and represented by Lori Trahan (D). The state's senior Senator is Elizabeth Warren (D). the state's junior Senator is Ed Markey (D).

In July 2012, Lowell youth led a nationally reported campaign to gain voting privileges for 17-year-olds in local elections; it would have been the first municipality to do so.[108][109] The 'Vote 17' campaign was supported by national researchers; its goals were to increase voter turnout, create lifelong civic habits, and increase youth input in local matters.[110] The effort was led by youth at the United Teen Equality Center in downtown Lowell.[79]

| Registered Voters and Party Enrollment as of February 15, 2012[111] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 20,420 | 40.48% | |||

| Republican | 4,542 | 9.00% | |||

| Unenrolled | 25,110 | 49.78% | |||

| Other | 374 | 0.74% | |||

| Total | 50,446 | 100% | |||

Voting rights lawsuit

Lowell is the last city in Massachusetts to use a fully plurality-at-large system due to its impact in diluting minority representation on its city council and school committee. With majority bloc voting these two committees were all-white, and had been mostly so for decades, despite the fact that the city's minority population had grown to 49%.[112]

On May 18, 2017, the Boston Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights and Economic Justice filed a federal lawsuit on behalf of Latino and Asian-American voters, charging Lowell with violating the Voting Rights Act.[112]

On May 29, 2019, a settlement agreement was reached that laid out six options for Lowell voters to review:[113]

- A single-member district-based system, with nine city council districts including at least two majority-minority districts, and three school committee districts electing two members each, with at least one being a majority-minority district.

- A hybrid system that combines single-member district-based seats with at-large seats:

- Hybrid 8-1 will have eight single-member districts (at least two majority-minority) and one at-large seat for the city council, and four single-member districts (at least one majority-minority) and two at-large seats for the school committee;

- Hybrid 8-3 is the same as 8-1 but expanding the city council by two at-large seats;

- Hybrid 7-2 will have seven single-member districts (at least two majority-minority) and two at-large seats for the city council, and seven single-member districts (at least two majority-minority) for the school committee (increasing its size by one);

- An at-large system of nine city council seats and six school committee seats, elected using single transferable vote — a return to the system in place between 1943 and 1957.

- A three-district system elected using single transferable vote, with three members from each elected to the city council and two members from each elected to the school committee.

Two options will be selected by the city council and will be put before the voters to choose in a non-binding referendum in November 2019, with a final decision by the city council in December 2019. The new system must be put in place by the November 2021 municipal elections.

Education

Colleges and universities

With a rapidly growing student population, Lowell has been considered an emerging college town.[114] With approximately 12,000 students at Middlesex Community College (MCC) and 18,500 students at University of Massachusetts Lowell, Lowell is currently home to more than 30,000 undergraduate, graduate and doctoral students, and the location of some of the top research laboratories in Massachusetts. UMass Lowell is the second largest state university and fifth largest university in Massachusetts, while MCC is the second largest Associate's college in Massachusetts.[115]

- Middlesex Community College

- University of Massachusetts Lowell

Primary and secondary schools

Public schools

Lowell Public Schools operates district public schools. Lowell High School is the district public high school. Non-district public schools include Greater Lowell Technical High School, Lowell Middlesex Academy Charter School,[116] Lowell Community Charter Public School,[117][118] and Lowell Collegiate Charter School.[119]

Lowell Public Schools is an above average, public school district located in Lowell, MA. It has 14,247 students in grades Pre-K, K–12 with a student-teacher ratio of 14 to 1.[120]

Lowell High School students have the opportunity to take Advanced Placement® course work and exams. The AP® participation rate at Lowell High is 29 percent. The student body makeup is 50 percent male and 50 percent female, and the total minority enrollment is 68 percent with a student-teacher ratio of 14 to 1.[121]

Media

Newspaper

The Sun, headquartered in downtown Lowell, is a major daily newspaper serving Greater Lowell and southern New Hampshire. The newspaper had an average daily circulation of about 42,900 copies in 2011.[122] Continuing a trend of concentration of newspaper ownership, The Sun was sold to newspaper conglomerate MediaNews Group in 1997 after 119 years of family ownership.[123]

Radio

- WCAP AM 980, talk radio

- WLLH AM 1400 Spanish Tropical

- WUML FM 91.5, UMass Lowell-owned station

- WCRB FM 99.5, Classical music, licensed to Lowell

Infrastructure

Transportation

Lowell can be reached by automobile from Interstate 495, U.S. Route 3, the Lowell Connector, and Massachusetts Routes: 3A, 38, 110, 113, and 133, all of which run through the city; Route 133 begins at the spot where Routes 110 and 38 branch off just south of the Merrimack River.[124] There are six bridges crossing the Merrimack River in Lowell, and four crossing the Concord River (not including the two for I-495).

For public transit, Lowell is served by the Lowell Regional Transit Authority (LRTA), which provides fixed route bus services and paratransit services to the city and surrounding area. OurBus has daily bus service to Worcester and New York City. Other service includes Merrimack Vallery Regional Transfer Authority (MVRTA) Route 41 to Lawrence, and the Coach Company bus to Foxwoods Resort Casino.

Lowell is also served at Lowell station by the MBTA's commuter rail Lowell Line, with several departures daily to and from Boston's North Station.

The Lowell National Historical Park provides a free streetcar between its various sites in the city center, using track formerly used to provide freight access to the city's mills. An expansion to expand the system to 6.9 mi (11.1 km) was planned but rejected in 2016.[125]

In addition to several car rental agencies, Lowell has four Zipcar rental locations convenient to Gallagher Terminal, the Downtown, and the three UMass Lowell campuses (North, South and East).

Hospitals

- Lowell General Hospital

- Saints Medical Center

Law enforcement

The city is primarily policed and protected by the Lowell Police Department, the University Police: UMass Lowell, and the National Park Service Police. The Massachusetts State Police and Middlesex County Sheriff's Office also work with local law enforcement to set up driver checkpoints for alcohol awareness. With the growth of UMass Lowell and the impact of its faculty and students in areas of scientific research, engineering, and nursing, the city has seen rapid gentrification of several neighborhoods.

Cable

Lowell Telecommunication Corporation[126] (LTC) – A community media and technology center

Notable people

- See List of people from Lowell, Massachusetts

Businesses started and products invented in Lowell

Current

The Massachusetts Medical Device Development Center (M2D2) Biotechnology Lab offers 11,000 square feet of fully equipped, shared lab facilities that can house 50 researchers and also includes plenty of co-working and meeting spaces.[127]

The UMASS Lowell Innovation Hub[128] (iHUB) offer entrepreneurs, startups, technology companies and established manufacturing partners 24-hour access to all the amenities they need to get their businesses up and running, such as:

- dedicated office space

- rapid prototype development equipment and services

- open co-working and collaboration space, and

- meeting and conferencing space.

Historical

- Cash Carriers – William Stickney Lamson of Lowell patented this system in 1881.

- CVS/pharmacy – originally named the Consumer Value Store was founded in Lowell in 1963.

- Father John's Medicine[129] a cough medicine that was first formulated in the United States in a Lowell pharmacy in 1855.

- Francis Turbine – A highly efficient water-powered turbine

- Fred C. Church – Insurance (est. 1865)[130]

- Market Basket – Chain of approximately 80 grocery stores in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine

- Moxie – the first mass-produced soft drink in the U.S.

- Telephone numbers, 1879, Lowell is the first U.S. city to have phone numbers, two years after Alexander Graham Bell demonstrates his telephone in Lowell.[131]

- Stuarts Department Stores

- Wang Laboratories – Massachusetts Miracle computer company

Banks and financial institutions

- In 1854, the Lowell Five Cent Savings Bank was founded as the first and only bank in the city that would accept a deposit of less than $1.00. It is the 73rd-oldest bank in America and has been in continuous operation since its founding.[132][133]

- In 1892, Washington Savings Bank made its first home in Lowell and has continuously served the Greater Lowell area and communities.[134][135]

- In 1989, Enterprise Bank and Trust was founded in Lowell and is the largest financial institution.[136][clarification needed]

- In 1911, Jeanne D'Arc Credit Union was founded in Lowell and is the 5th-largest credit union in Massachusetts.[137][138]

- In 1922, Align Credit Union was founded in Lowell.[139]

- In 1936, the Lowell Firefighters Credit Union was founded in Lowell.[140]

- In 1937, the Lowell Municipal Employees FCU was founded in Lowell.[141]

- In 1958, Mills42 Federal Credit Union was founded in Lowell.[142]

Merged financial institutions

- Lowell Bank and Trust Company (1970–1983; now part of Bank of America)[143]

- Lowell Institution for Savings (1829–1991; now part of TD Banknorth N.A.)[144]

- Butler Bank (1901–2010; now part of People's United Bank)[145][146]

- Lowell Co-operative Bank/Sage Bank (1885–2018; now part of Salem Five Bank)[147]

Twin towns – sister cities

Lowell's sister cities are:[148]

Bamenda, Cameroon (2002)

Bamenda, Cameroon (2002) Barclayville, Liberia

Barclayville, Liberia Berdyansk, Ukraine (1997)

Berdyansk, Ukraine (1997) Kalamata, Greece (2020)[149]

Kalamata, Greece (2020)[149] Nairobi, Kenya

Nairobi, Kenya Limerick, Ireland (2013)[150]

Limerick, Ireland (2013)[150] Lobito, Angola

Lobito, Angola Phnom Penh, Cambodia (2015)[151]

Phnom Penh, Cambodia (2015)[151] Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, France (1989)

Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, France (1989) Winneba, Ghana (2010)

Winneba, Ghana (2010)

Honors

- 2010, Lowell designated as a "Green Community"[152]

- 1997 and 1998, Lowell was a finalist for the All-American City award.[153]

- 1999, Lowell received an All-American City award.[153]

See also

- List of mill towns in Massachusetts

References

- "FAQ City of Lowell, Massachusetts". City of Lowell, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- "Boston - Cambridge - Newton, MA-NH Metropolitan Statistical Area (USA): Places - Population Statistics in Maps and Charts".

- "Lowell National Historical Park". nps.gov. U.S. Department of the Interior.

- "Monument in Lowell the Cambodian community's past and its progress - The Boston Globe". The Boston Globe.

- "Profile for Lowell, Massachusetts, MA". ePodunk. Archived from the original on May 15, 2019. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- Stephen J. Goldfarb, "A Note on Limits to Growth of the Cotton-Textile Industry in the Old South," Journal of Southern History, 48, (1982), 545.

- Beckert, Sven (2014). Empire of Cotton: a Global History. New York: Knopf.

- Marion, Paul, "Timeline of Lowell History From 1600s to 2009", Yankee magazine, November 2009.

- City of Lowell Master Plan Update: Existing Conditions Report, Department of Planning and Development, December 2011, 3.0 Land-Use pg 31

- City of Lowell Master Plan Update: Existing Conditions Report, Department of Planning and Development, December 2011, 3.0 Land-Use pg 32

- Hamilton Canal District Form-Based Code Zoning Section, City of Lowell Zoning Section 10.3, February 2009 pg 4

- "Hamilton Canal District, Lowell, Massachusetts". trinityfinancial.com. Trinity Financial LLC. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014.

- Hamilton Canal District Master Plan, September 2008 pg. 6

- "CQ Press: City Crime Rankings 2009". Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- "City of Lowell". Archived from the original on May 13, 2012.

- Lowell-Dracut-Tyngsboro State Forest

- "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). 1: Number of Inhabitants. Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-7 through 21-09, Massachusetts Table 4. Population of Urban Places of 10,000 or more from Earliest Census to 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Table DP-1: Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010; 2010 Demographic Profile Data". US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- "Sustainable Lowell 2025" (PDF). lowellma.gov. p. xx. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- "Table QT-P1: Age Groups and Sex: 2010; 2010 Census Summary File 1". US Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- "State and County Quick Facts: Lowell (city) Massachusetts". US Census Bureau Quick Facts. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 4, 2014. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- "Table DP03 -- SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS; 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". US Census Bureau, 2006-2010 American Community Survey. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020.

- "Lowell (city), Massachusetts". American Community Survey 2013 1-year estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016.

- "Ethnicity in Lowell: Lowell National Historical Park Ethnographic Overview and Assessment" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 26, 2015 – via University of Lowell, Massachusetts Libraries.

- "Cambodian Consulate Opens in Lowell", Khmerization, April 27, 2009, accessed October 26, 2010

- "FBI DATA: #50 to #1: MA's Most Dangerous Cities and Towns – Where Does Worcester Rank?". This Week In Worcester. September 26, 2017. Archived from the original on May 4, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- "Lowell, MA Crime Rates and Statistics - NeighborhoodScout". www.neighborhoodscout.com. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- "FBI data reveals some of the lowest-crime cities in nearly every US state". Business Insider. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- "Lowell Women's Week".

- "Lowell Film Festival in Lowell, Massachusetts - Lowell.com". Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- "Welcome — Doors Open Lowell - National Preservation Month".

- "Home". African Festival Lowell.

- "Lowell Water Festival".

- "Lowell Kinetic Sculpture Race".

- "Lowell Celebrates Kerouac!".

- Marion, Paul (1999). Atop an Underwood. Penguin Group. p. xxi.

- "WESTERN AVENUE - STUDIOS & LOFTS – Lowell MA".

- Schweitzer. Sarah. "Lowell hopes to put 'Little Cambodia' on the map." The Boston Globe. February 15, 2010. Retrieved on February 15, 2012.

- "New York Times" article "Destruction of the Lowell Museum by Fire" January 31, 1856

- LHS - Lowell Historical Society Archived June 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "119 Gallery (911 Electronic Media Arts, Inc.) - Art, Music, Performance, and Community – Lowell MA". Archived from the original on March 30, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- "Arts League of Lowell". artsleagueoflowell.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "American Textile History Museum - Telling America's story through the art, history, and science of textiles".

- "Welcome to Ayer Lofts Art Gallery".

- "The Brush Art Gallery and Studios".

- "Gallery Z". facebook.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "Lowell Gallery".

- "Milling Around In Lowell". Org. May 18, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- "National Streetcar Museum: Lowell, Massachusetts".

- "NEQM Home".

- "Loading Dock Gallery". Loading Dock Gallery. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "University Gallery | UMass Lowell". uml.edu. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "Angkor Dance Troupe".

- Tuttle, Nancye, "Cambodian art, a New England tradition", The Lowell Sun, May 15, 2008.

- "Arts League of Lowell".

- Pohl, Janet. "University of Massachusetts Center for Lowell History".

- Durant, Jeri. "Gentlemen Songsters Barbershop Harmony Chorus - Family Entertainment in the A Cappella Style - 2016".

- "Home".

- "Home".

- "Lowell Poetry Network". Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- "Lowell Rocks".

- "Lowell Summer Music Series".

- "Music Department - UMass Lowell".

- "Homepage - UTEC, Inc".

- "UnchARTed". facebook.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- C.B. Tillinghast. The free public libraries of Massachusetts. 1st Report of the Free Public Library Commission of Massachusetts. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1891. Google books

- "Library History". Pollard Memorial Library.

- "Community Investments". City of Lowell. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- "Hours & Locations". Pollard Memorial Library.

- July 1, 2007 through June 30, 2008; cf. The FY2008 Municipal Pie: What's Your Share? Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Board of Library Commissioners. Boston: 2009. Available: Municipal Pie Reports Archived January 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 4, 2010

- July 1, 2008 through June 30, 2009; cf. Massachusetts Board of Library Commissioners (2011). "FY 2009 Municipal Pie Report". Archived from the original on January 23, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- Pollard Memorial Library. "Databases". Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- "Dyeing for a living: a history of the American Association of Textile" By Mark Clark

- "Lydon Library". UMass Lowell Libraries. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015.

- "Olearyforcongress.com". Archived from the original on July 14, 2011.

- "O'Leary Library". UMass Lowell Libraries. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017.

- "Center for Lowell History". University of Massachusetts Lowell Libraries.

- Halloran, Bob (2010). Irish Thunder: The Hard Life and Times of Micky Ward. Guilford, CT: First Lyons Press.

- Sackowitz, Karen (June 10, 2010). "Blood, sweat, cheers: Lowell gym helps youths learn boxing, confidence, and it stars in a new movie". The Boston Globe.

- "Lowell Nor'easter - New England Football League". Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- "THE NPSL COMES TO LOWELL, MA". NPSL. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2013.

- "New soccer team in Lowell will join Premier League". Lowell Sun. November 20, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- "Boathouse & Kayak Center". Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

- "longmeadowgolfclub". longmeadowgolfclub. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "mpgc.net". mpgc.net. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "City of Lowell". Archived from the original on December 31, 2010.

- "Overview". City of Lowell. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- Santucci, Jack (November 10, 2016). "Party Splits, Not Progressives". American Politics Research. 45 (3): 494–526. doi:10.1177/1532673x16674774. ISSN 1532-673X. S2CID 157400899.

- Moran, Lyle (April 15, 2014). "Lowell City Manager Murphy ready to roll up his sleeves". Lowell Sun. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- "Donoghue sworn in as city manager, and gets right down to work". Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- Smith, Margaret (September 1, 2020). "Howard wins primary in 17th Middlesex race". Wicked Local.

- "Massachusetts Representative Districts". Sec.state.ma.us. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- Plaisir, Corinne; Kirksey, Carline (July 24, 2012). "Let 17-year-olds vote". Archived from the original on July 30, 2012.

- Line, Molly (July 11, 2012). "'Vote 17' movement pushing for teen voice in local elections". Fox News.

- "my testimony in favor of lowering the voting age to 17 in Lowell, MA". April 13, 2011.

- "Registered Voters and Party Enrollment as of February 15, 2012" (PDF). Massachusetts Elections Division. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- "Minority Residents Allege City's At-Large Electoral System Unlawfully Dilutes Their Vote". Lawyers for Civil Rights. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- "Settlement of Federal Voting Rights Act Case Against Lowell, Mass". Lawyers for Civil Rights. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- Moran, Lyle (August 4, 2014). "City manager wants to make Lowell a 'college town'". The Sun.

- "UMass Lowell Demographics". National Center for Education Statistics.

- "Lowell Middlesex Academy Charter School".

- "Home Page - Lowell Community Charter Public School".

- "About the School". LCCPS.org.

- SABIS®. "Collegiate Charter School of Lowell".

- "Explore Lowell Public Schools". Niche. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "Best High Schools/Massachusetts". US News. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "eCirc for US Newspapers: FAS-FAX Report". Audit Bureau of Circulations. September 30, 2011. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- Revah, Suzan (September 1997). "Bylines". American Journalism Review. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- "City of Lowell - Location". Archived from the original on October 8, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- Welker, Grant (February 16, 2016). "Expanded Lowell trolley plans derailed". Lowell Sun. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- "Home - LTC".

- "M2D2 110 Canal | UMass Lowell". uml.edu. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "iHub | UMass Lowell". uml.edu. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- Pohl, Janet. "Father John's Story".

- Fredcchurch.com

- "Timeline of Lowell History". October 8, 2009. Archived from the original on December 4, 2009. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- "iBanknet | America's Oldest Banks". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- "The Lowell Five Cent Savings Bank Financial Reports". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "Our History | Washington Savings Bank | Lowell - Dracut | Massachusetts - MA". washingtonsavings.com. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- "Washington Savings Bank Financial Reports". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "Enterprise Bank and Trust Company Financial Reports". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "JEANNE D'ARC CREDIT UNION Financial Reports". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "iBanknet | Massachusetts - Credit Unions". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "ALIGN CREDIT UNION Financial Reports". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "LOWELL FIREFIGHTERS CREDIT UNION Financial Reports". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "LOWELL MUNICIPAL EMPLOYEES FEDERAL CREDIT UNION Financial Reports". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "MILLS42 FEDERAL CREDIT UNION Financial Reports". ibanknet.com. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- "Lowell Bank and Trust Company". usbanklocations.com. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- "Lowell Institution for Savings". usbanklocations.com. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- DRR. "FDIC: Failed Bank Information - Bank Closing Information for Butler Bank, Lowell, MA". fdic.gov. Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- "Like namesake general, Butler Bank fought to end". Retrieved May 7, 2018.

- Lisinski, Chris (August 20, 2018). "Salem Five closes on acquisition of Sage Bank". Lowell Sun. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "Across globe, building bridges". lowellsun.com. The Sun. June 3, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- "Lowell, Massachusetts and Kalamata, Greece to Become Sister Cities". greekreporter.com. Greek Reporter. February 12, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- "Limerick council to send Mayor to Boston for twinning". Limerick Leader. January 26, 2016. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- "Lowell delegation visits Cambodia, returns with sister city deal, perspective". lowellsun.com. The Sun. February 1, 2015. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- "City Council gets wind of green bonus". May 26, 2010.

- NCL.org Archived July 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

| Library resources about Lowell, Massachusetts |

- Dalzell, Robert F. Enterprising elite: The Boston Associates and the world they made (Harvard University Press, 1987)

- Deitch, Joanne Weisman. The Lowell Mill Girls: Life in the Factory (Perspectives on History Series) (1998)

- Dublin, Thomas. Women at Work: The Transformation of Work and Community in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1826-1860, (Columbia University Press, 1981)

- Eno, Arthur Louis. Cotton was king: A history of Lowell, Massachusetts (New Hampshire Publishing Company, 1976)

- Gross, Laurence F. The Course of Industrial Decline: The Boott Cotton Mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, 1835-1955 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993)

- Malone, Patrick M., Waterpower in Lowell: Engineering and Industry in Nineteenth-Century America, Johns Hopkins Introductory Studies in the History of Technology (2009)

- Mrozowski, Stephan A.; Ziesing, Grace H.; Beaudry, Mary C., Living on the Boott: Historical Archaeology at the Boott Mills Boardinghouses, Lowell, Massachusetts, The Lowell Historic Preservation Commission (1996)

- Savard, Rita, "Three Hard Words: I Need Help: Jobs gone and bills mounting, many more in Greater Lowell seek food aid", The Lowell Sun, January 22, 2010

- Stanton, Cathy, The Lowell Experiment: Public History in a Postindustrial City, University of Massachusetts Press. (2006)

- Weible, Robert, ed. The Continuing Revolution: A History of Lowell, Massachusetts (1991)

Primary sources

- Denenberg, Barry. So Far From Home: The Diary of Mary Driscoll, An Irish Mill Girl, Lowell, Massachusetts 1847 (Dear America Series) (2003)

- Eisler, Benita, The Lowell Offering: Writings by New England Mill Women (1840-1845), J.B. Lippincott (1977); Norton (1998)

- Larcom, Lucy, "Among Lowell Mill-Girls: a reminiscence", The Atlantic Monthly, v.XLVIII (48), no.268, November 1881, pp. 593–612.

- The Lowell Historical Society, Lowell: The Mill City (MA) (Postcard History Series), Arcadia Publishing. (2005), illustrated postcards

External links

- City of Lowell official web site

- Merrimack Valley Region tourist information

- University of Massachusetts Lowell, Center for Lowell History

- Lowell Folklife Project, Library of Congress

- . The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

На других языках

[de] Lowell (Massachusetts)

Lowell ist eine Stadt in Middlesex County im US-Bundesstaat Massachusetts in den USA. Das U.S. Census Bureau hat bei der Volkszählung 2020 eine Einwohnerzahl von 115.554[2] ermittelt.- [en] Lowell, Massachusetts

[ru] Лоуэлл (Массачусетс)

Лоуэлл — город в округе Мидлсекс, штат Массачусетс, США. На 2014 год население составило 109 645 человек.[3] Четвертый по величине город штата. Является одним из административных центров северной части округа Мидлсекс.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии