world.wikisort.org - USA

Framingham (/ˈfreɪmɪŋhæm/ (![]() listen)) is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. Incorporated in 1700, it is located in Middlesex County and the MetroWest subregion of the Greater Boston metropolitan area. The city proper covers 25 square miles (65 km2) with a population of 72,362 in 2020,[2] making it the 14th most populous municipality in Massachusetts.[3] Residents voted in favor of adopting a charter to transition from a representative town meeting system to a mayor–council government in April 2017, and the municipality transitioned to city status on January 1, 2018.[4]

listen)) is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. Incorporated in 1700, it is located in Middlesex County and the MetroWest subregion of the Greater Boston metropolitan area. The city proper covers 25 square miles (65 km2) with a population of 72,362 in 2020,[2] making it the 14th most populous municipality in Massachusetts.[3] Residents voted in favor of adopting a charter to transition from a representative town meeting system to a mayor–council government in April 2017, and the municipality transitioned to city status on January 1, 2018.[4]

Framingham, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

City | |

|

Left-right from top: Memorial Hall in Concord Square Historic District, Framingham Common, Framingham State University, Callahan State Park | |

Seal | |

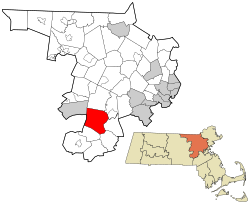

Location in Middlesex County in Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 42°16′45″N 71°25′00″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Middlesex |

| Region | New England |

| Settled | 1650 |

| Incorporated (town) | June 25, 1700 |

| Incorporated (city) | January 1, 2018 |

| Named for | Framlingham, Suffolk |

| Government | |

| • Type | City |

| • Mayor | Charlie Sisitsky |

| • City council | George King, Chair Adam Steiner, Vice-Chair Janet Leombruno Christine Long Cesar Stewart-Morales Michael Cannon Noval Alexander Phil Ottoviani Leora Mallach John Stefanini Tracey Bryant |

| Area | |

| • Total | 26.50 sq mi (68.65 km2) |

| • Land | 25.04 sq mi (64.86 km2) |

| • Water | 1.46 sq mi (3.78 km2) |

| Elevation | 165 ft (50 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 72,362 |

| • Density | 2,889.39/sq mi (1,115.61/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Codes | 01701 and 01702 |

| Area code | 508/774 |

| FIPS code | 25-24925 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0618224 |

| Website | www |

History

Framingham, sited on the ancient trail known as the Old Connecticut Path, was first settled by a European when John Stone settled on the west bank of the Sudbury River in 1647. Native American leader Tantamous lived in the Nobscot Hill area of Framingham prior to King Philip's War in 1676. In 1660, Thomas Danforth, an official of the Bay Colony, formerly of Framlingham, Suffolk, received a grant of land at "Danforth's Farms" and began to accumulate over 15,000 acres (100 km2). He strenuously resisted petitions for incorporation of the town, which was officially incorporated in 1700, following his death the previous year. Why the "L" was dropped from the new town's name is not known. The first church was organized in 1701, the first teacher was hired in 1706, and the first permanent schoolhouse was built in 1716.

On February 22, 1775, the British general Thomas Gage sent two officers and an enlisted man out of Boston to survey the route to Worcester, Massachusetts. In Framingham, those spies stopped at Buckminster's Tavern. They watched the town militia muster outside the building, impressed with the men's numbers but not their discipline. Though "the whole company" came into the tavern after their drill, the officers remained undetected and continued on their mission the next day.[5] Gage did not order a march along that route, instead ordering troops to Concord, Massachusetts, on April 18–19. Framingham sent two militia companies totaling about 130 men into the Battles of Lexington and Concord that followed; one of those men was wounded.[6]

In the years before the American Civil War, Framingham was an annual gathering-spot for members of the abolitionist movement. Each Independence Day from 1854 to 1865, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society held a rally in a picnic area called Harmony Grove near what is now downtown Framingham. At the 1854 rally, William Lloyd Garrison burned copies of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, judicial decisions enforcing it, and the United States Constitution. Other prominent abolitionists present that day included William Cooper Nell, Sojourner Truth, Wendell Phillips, Lucy Stone, and Henry David Thoreau.[7]

During the post-World War II baby boom, Framingham, like many other suburban areas, experienced a large increase in population and housing. Much of the housing constructed during that time consisted of split-level and ranch-style houses.

Framingham is known for the Framingham Heart Study, as well as for the Dennison Manufacturing Company, which was founded in 1844 as a jewelry and watch box manufacturing company by Aaron Lufkin Dennison, who became the pioneer of the American System of Watch Manufacturing at the nearby Waltham Watch Company. His brother Eliphalet Whorf Dennison developed the company into a sizable industrial complex which merged in 1990 into Avery Dennison, with headquarters in Pasadena, California, and active corporate offices in the town.

In 2000, Framingham celebrated its Tercentennial. Framingham soon rose to become the largest town in Massachusetts, commonly referred to by the people of Framingham as "The largest town in the country." Framingham had attempted to become a city on three prior occasions 1993, 1997, and 2013, all of which were rejected by the people of Framingham.[8] However, on January 1, 2018, Framingham became a city and Yvonne M. Spicer was inaugurated as its first mayor, thus becoming the first popularly elected African-American female mayor in Massachusetts.[9]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 26.4 square miles (68.5 km2). 25.1 square miles (65.1 km2) of it is land and 1.3 square miles (3.4 km2) of it (4.99%) is water.[10]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 4,252 | — |

| 1860 | 4,227 | −0.6% |

| 1870 | 4,968 | +17.5% |

| 1880 | 6,235 | +25.5% |

| 1890 | 9,239 | +48.2% |

| 1900 | 11,302 | +22.3% |

| 1910 | 12,948 | +14.6% |

| 1920 | 17,033 | +31.5% |

| 1930 | 22,210 | +30.4% |

| 1940 | 23,214 | +4.5% |

| 1950 | 28,086 | +21.0% |

| 1960 | 44,526 | +58.5% |

| 1970 | 64,048 | +43.8% |

| 1980 | 65,113 | +1.7% |

| 1990 | 64,989 | −0.2% |

| 2000 | 66,910 | +3.0% |

| 2010 | 68,318 | +2.1% |

| 2020 | 72,362 | +5.9% |

Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[21] | ||

As of the census of 2010,[22] there were 68,318 people, 26,173 households, and 16,535 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,732.7 people per square mile (1,054.3/km2). There were 27,529 housing units, of which 1,356, or 4.9%, were vacant. The racial makeup of the city was 71.9% White, 5.8% Black, 0.3% Native American, 6.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 10.9% from some other race, and 4.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 13.4% of the population (4.7% Puerto Rican, 1.8% Guatemalan, 1.5% Salvadoran, 1.1% Dominican, 0.9% Mexican, 0.6% Colombian, 0.3% Peruvian). (Source: 2010 Census Quickfacts)

Of the 26,173 households, 31.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.2% were headed by married couples living together, 10.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.8% were non-families. 28.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.0% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47, and the average family size was 3.03.[22]

As of 2010, 20.9% of the population were under the age of 18, 9.8% were from 18 to 24, 30.0% were from 25 to 44, 25.8% were from 45 to 64, and 13.6% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.0 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.8 males.[23]

In 2017, the estimated median income for a household in the city was $84,050, and the median income for a family was $101,078. Male full-time workers had a median income of $61,659, versus $54,714 for females. The per capita income for the city was $38,917. About 7.5% of families and 11.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.7% of those under age 18 and 9.4% of those age 65 or over.[24]

Brazilian immigrants have a major presence in Framingham.[25][26][27][28] Since the 1980s, a large segment of the Brazilian population has come from the single city of Governador Valadares.[29]

Government and politics

Framingham's Home Rule Charter was approved by voters on April 4, 2017, and took effect on January 1, 2018.[30] On that date, Yvonne M. Spicer was inaugurated as Framingham's first mayor.

Elections are held in November of odd-numbered years, to elect a full-time mayor serving a four-year term, and an 11-member city council comprising nine district members serving two-year terms, and two at-large members serving four-year terms. The mayor replaced the Board of Selectmen as the chief executive, and the City Council replaced Representative Town Meeting as the legislative body. The Mayor and at-large-councilors are limited to a maximum of three consecutive terms in office and district councilors are limited to six consecutive terms in office.[31]

The School Committee has ten members: one elected from each of the nine districts, serving two-year terms, and the mayor, who serves as a tenth member and may only vote to break a tie.[31]

The Board of Library Trustees and the Board of Cemetery Trustees have also elected positions serving for four-year terms, with half the membership elected at alternating municipal elections.[31]

The Charter provides for an automatic review of the Charter five years after its adoption and periodically thereafter.[31]

The city maintains a police department.[32]

Education

The Framingham School Department can trace its roots back to 1706 when the town hired its first schoolmaster, Deacon Joshua Hemenway. Although Framingham had its first schoolmaster, it did not get its own public school building until 1716. The first high school, the Framingham Academy, opened its doors in 1792; however, this school was eventually closed due to financing issues and the legality of the town providing funds for a private school. The first town-operated high school opened in 1852 and has been in operation continuously in numerous locations throughout the town.[33]

Framingham has 14 public schools which are part of the Framingham Public School District.[34] This includes Framingham High School, three middle schools (Walsh, Fuller, and Cameron), nine elementary schools (Barbieri, Brophy, Dunning, Hemenway, King, McCarthy, Potter Road, Stapleton, Woodrow Wilson), and the Blocks Pre-School.[34] The school district's main offices are located in the Fuller Administration Building on Flagg Drive[35] with additional offices at the King School on Water Street. The city also has a regional vocational high school[36] and one regional charter school.[37] Framingham is also home to several private schools, including Summit Montessori School, the Sudbury Valley School, one parochial school, one Jewish day school, and several specialty schools.

Since 1998, when Framingham began upgrading its schools, it has performed major renovations to Cameron, Wilson, McCarthy, and Framingham High School. Two public school buildings that were mothballed due to financial issues or population drops have been leased to the Metrowest Jewish Day School (at the former Juniper Hill Elementary) and Mass Bay Community College (at the former Farley Middle school). Several schools that were no longer being used were sold off, including Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Washington.

Framingham has three colleges, including Framingham State University and Massachusetts Bay Community College's Framingham Campus.

Transportation

Framingham is approximately halfway between Worcester, the commercial center of Central Massachusetts, and Boston, New England's leading port and metropolitan area. Rail and highway facilities connect these major centers and other communities in the Greater Boston Metropolitan Area.[38]

Air

The closest airport with scheduled international passenger traffic is Boston's Logan International Airport, 25 miles (40 km) from Framingham. Worcester Regional Airport, about 27 miles (43 km) away, began scheduled flights to Fort Lauderdale and Orlando in November 2013.

Major highways

Framingham is served by one Interstate and four state highways:

| Route number | Type | Local name | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interstate, limited access toll road | The Massachusetts Turnpike (Mass Pike) | east/west | |

| State route, divided highway | Worcester Rd. The Boston/Worcester Turnpike, Ted Williams Highway |

east/west | |

| State route, partial divided highway | Cochituate Rd., Worcester Rd. and Pleasant St. | east/west | |

| State route, primary road | Old Connecticut Path, School St, Concord St., and Hollis St. | north/south | |

| State route, primary road | Waverly St. | east/west |

Mass transit

Rail

- Direct rail service to Boston and Chicago via Amtrak's Lake Shore Limited, as well as to all other points on the Amtrak network via a connection in another city.

- MBTA commuter rail service is available to South Station and Back Bay Station, Boston, via the MBTA's Framingham/Worcester Line, which connects South Station in Boston and Union Station in Worcester. Travel time to Back Bay Station is 42–45 minutes. It was called the Framingham Commuter Rail Line, as Framingham was the end of the line, until rail traffic was expanded to Worcester in 1996.[39] The line also serves Newton, Wellesley, Natick, Ashland, Southborough, Westborough, and Grafton.[40]

- CSX provides freight rail service in Framingham.

Bus

- MassPort operates the Logan Express[41] bus service seven days per week providing a direct connection to Logan Airport. The bus terminal and paid parking facility are on the Shoppers' World Mall property, off the Massachusetts Turnpike exit 13, between Route 9 and Route 30.

- Peter Pan Bus Lines provides service to Worcester, New York, and Boston.

- The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), provides THE RIDE, a paratransit service for the elderly and disabled.

- The MetroWest Regional Transit Authority (MWRTA)[42] operates a regional bus service which provides service to other local routes connecting the various regions of town and fixed route public bus lines servicing multiple communities in the MetroWest region, including the towns of Ashland, Holliston, Hopkinton, Milford, Marlborough, Sudbury, Sherborn, Natick, and Weston.[43][44]

Commuter services

Park and ride services:[45]

- MassDOT operates a free park and ride facility at the parking lot at the intersection of Flutie Pass and East Road on the south side of Shoppers' World Mall.[46]

- MassDOT also operates a free park and ride facility at a parking lot adjacent to exit 12 of the Massachusetts Turnpike, across from California Avenue on the west side of Framingham.[46]

Economy

Framingham's economy is predominantly derived from retail and office complexes. There are scatterings of small manufacturing facilities and commercial services such as plumbing, mechanical and electrical expected to be found in communities of its size. Framingham has three major business districts within the city, The "Golden Triangle", Downtown/South Framingham, and West Framingham. Additionally, there are several smaller business hubs in the villages of Framingham Center, Saxonville, Nobscot, and along the Route 9 corridor.

Golden Triangle

The Golden Triangle was originally a three square mile district on the eastern side of Framingham, bordered by Worcester Rd. (Route 9), Cochituate Rd. (Route 30), and Speen Street in Natick. In 1993, the area began to expand beyond the borders of the triangle with construction of a BJ's Wholesale Club and a Super Stop & Shop just north of Route 30.[47] It now includes the original area plus parts of Old Connecticut Path., Concord St. (Route 126), and Speen St. north of Route 30. Because of the size and complexity of this area, Framingham and Natick cooperatively operate it as a single distinct district with similar zoning. The area is one of the largest shopping districts in New England.[citation needed]

The area was formed with the construction of Shoppers World in 1951. Shoppers' World was a large open air shopping mall, the second in the US and the first east of the Mississippi River.[48] The mall drew many other retail construction projects to the area, including Marshalls (1961, rebuilt as Bed, Bath and Beyond 1997),[49] Caldor (1966, Rebuilt as Wal-Mart in 2002),[50] Bradlees (1960s, rebuilt as Kohl's in 2002),[51] the Route 30 Mall (1970),[52] an AMC Framingham 15, the Framingham Mall (1978, rebuilt 2000),[53] and Lowe's (formerly the Verizon Building, 2006).[54] Complementary developments in Natick include the Natick Mall (1966, rebuilt in 1991, expanded 2007 & renamed Natick Collection),[55] Sherwood Plaza (1960),[56] Cloverleaf Marketplace (1978),[57] and the Home Depot. In 1994, Shoppers' World was demolished and replaced with a strip mall named Shoppers World.[58] There are also seven hotels and two car dealerships located within the Triangle.

In addition to retail properties, there are large office developments in the area including several companies headquartered in the triangle; the world headquarters of TJX is at the junction of Route 30 and Speen St,[59] as is the main office of IDG and IDC.[60] The American Cancer Society has an office in Framingham.[61] A Carling Brewery began operations in 1956, ending in 1975. Their buildings later housed Prime Computer and Boston Scientific before demolition in 2018 for a new MathWorks facility.[62] Sealtest had a manufacturing facility in Framingham[63] which was used by Breyers from 1964 to 2011[64]

Downtown and South Framingham

The downtown area is between Memorial Square, formed by the intersection of Concord St. and Union Ave., to the north, and its mirror intersection at the junction of Irving St. and Hollis St. on the south end. The area is bisected by Waverly St. (Route 135) and the MBTA Commuter Rail tracks. The anchoring structure of Downtown is the city hall, The Memorial Building.[65] From 2015 to 2016, the whole area underwent a multimillion-dollar reconstruction of the intersection of Union Ave. and Concord St. that replaced the traffic circle with a signal-controlled intersection. Additional lights were installed at the Irving St./Hollis St. intersection, while older signals in the area were upgraded. All sidewalks in the area were to be replaced, lighting upgraded, and new amenities such as seating and bicycle racks were also installed. The project was scheduled to begin in 2012 but has been delayed to 2014–2015.[66][67] Further delays pushed the project into 2015 due to needed electrical utility upgrades and replacement.[68]

South Framingham became the commercial center of the town with the advent of the railroad in the 1880s. It eventually came to house Dennison Manufacturing and the former General Motors Framingham Assembly plant, but the area underwent a financial downturn after the closure of these facilities during the late 1980s.[69] An influx of Hispanic and Brazilian immigrants helped to revitalize the district starting in the early 2000s. Along with Brazilian and Spanish oriented retail shops, there are restaurants, legal and financial services, the city offices and library, police headquarters, a performing arts center, and the local branch of the Social Security Administration. Several Asian and Indian stores and restaurants add to the rich ethnic flavor of the area, and many small businesses, restaurants and automotive-oriented shops line Waverly St. from Natick in east to Winter St. in the west.[70]

In 2006, the Fitts Market & Hemenway buildings façades underwent a restoration project; these newly renovated structures received a 2006 Massachusetts Historical Commission Preservation Award in the Restoration and Rehabilitation Category.[71] In addition, several retail and housing projects involving the Arcade Building and the former Dennison Building Complex are in the planning stages or under construction.[72][73]

West Framingham

The business section on the West Side of Framingham runs primarily along Route 9, starting at Temple St., and is dominated by two large office/industrial parks: the Framingham Industrial Park on the north side of Route 9 and another park on the south side, both on the Framingham/Ashland/Southborough border. Bose, Staples and Applause have their world headquarters in these parks,[74] as does convenience store chain Cumberland Farms; in addition, Netezza, Genzyme, Capital One, CA Technologies, ITT Tech and the local paper, The MetroWest Daily News, all have major facilities there. Two of Framingham's seven major auto dealerships are also in West Framingham: Ford and Toyota/Scion.[75][76]

The large tracts of multi-story apartment and condominium complexes line both sides of Route 9 from Temple St. to the industrial parks. These buildings represent the majority of Framingham's multi-family dwellings, and along with the business complexes, helped create a large network of support services on the West Side: Framingham's second Super Stop & Shop supermarket,[77] dozens of restaurants and pubs, Sheraton Hotel & Conference Center[78] and Residence Inn by Marriott[79] hotels and a large day-care facility all are in the two-mile (3 km) section of Route 9 from Temple St. to Ashland.

Villages and Route 9

The Framingham Centre Common Historic District is the city's physical and historic center. Formed at the junctions of Worcester Rd. (Route 9), Pleasant St. (Route 30), High St., Main St. and Edgell Rd.[80] the dominating presence is Framingham State University. The school has several thousand students, about one third of whom live on campus.[81] In the late 1960s, MassHighway replaced the intersection with an overpass, depressing Route 9 below the local roads, and destroying the south half of the old Center retail district. The remaining half houses several small stores, restaurants, realtors and legal offices. The old Boston and Worcester Street Railway depot, on the east side of the center, was converted into a strip mall in the early 1980s and houses the Center Postal Station (01703) and several small stores.[82] The center is rounded out by One and Two Edgell Rd. (two small retail/office buildings), the historic village hall,[83] the Jonathan Maynard Building (a former school converted to an office building which now houses most of the school district's administration), the Framingham History Center (formerly the Framingham Historical Society and Museum),[84] several banks, a Chinese restaurant, the American Medical Response paramedic station and McCarthy Office Building.

The village of Nobscot, at the intersection of Water St., Edmands Rd. and Edgell Rd. near Nobscot Hill, and the Pinefield/Saxonville villages, located where Concord St., Water St., and Central St. intersect,[85][86] are home to several small office buildings, strip malls and gas stations. in 2016, the town moved its satellite branch of the public library named for Christa McAuliffe from Saxonville to a new facility across from the Hemenway School in Nobscot. Saxonville is the home of the former Roxbury Carpet Company buildings, now an industrial park, and is one of the city's historical districts.

In addition the section of Route 9 from the Route 126 overpass to the Main St./Edgell Rd. beetleback in Framingham Center is heavily developed. Three car dealerships, Acura, Chevrolet and Hyundai, several strip malls of varying sizes, many small apartment complexes, several small office complexes and other small shops and restaurants make Route 9 the main commercial thoroughfare in Framingham.

Finally, there are several other small retail areas and facilities throughout the city, e.g. near Mt Wayte Ave. and Franklin St.; the intersection of Concord St. and Hartford St.; and along School St., near Hamilton St.

Healthcare

Framingham is served by MetroWest Medical Center (formerly Framingham Union Hospital, which also includes Leonard Morse Hospital campus in Natick)

Media

Newspapers and websites

The City of Framingham is served by:

- Framingham Source,[87] a local news website.[88]

- Framingham Online News, a local news and community information website.[89]

- The MetroWest Daily News, a daily broadsheet.[90]

- The Framingham Tab, a weekly local current events tabloid.[91]

- The Boston Globe provides a regional edition called Globe West that covers Framingham and the MetroWest area.[92]

- Boston.com has a Your Town website that covers Framingham.[93]

- A Semana, a weekly, Brazilian-Portuguese language local current events tabloid.[94]

- The Gatepost, a weekly student run newspaper published by Framingham State University.[95]

Television and cable

Framingham has a public, educational, and government access (PEG) cable TV channel and local origination television station called Access Framingham (formerly FPAC-TV),[96] that airs on Channel 9 Comcast, Channel 3 RCN and Channel 43 Verizon. Residents can create and produce their own television programs that reflect the personality of the community, and have them cablecast on the public-access television cable TV channels.

Framingham High School has a student-run television station, FHS-TV, that broadcasts locally; "Flyer News", its morning news program, has won 11 National High School Emmy Awards.

The City of Framingham operates the Government Channel shown on Comcast channel 99, RCN 13/HD613, and Verizon 42. The Government Channel operation provides programming sponsored by or for the City of Framingham. Commission meetings are cablecast live to inform residents and encourage participation in local government. Some of the programming provided, keeps residents abreast of road closings, construction updates, recycling efforts, public safety information, and special events in the community. The Government Channel is committed to making local government more accessible to all residents.

Radio

- WXKS (AM 1200) is an AM broadcasting station featuring talk radio and religious programming. Owned by iHeartMedia and licensed to Newton, Massachusetts with studios on 99 Revere Beach Parkway in Medford, Massachusetts;[97]

- WSRO (AM 650) is an AM broadcasting station featuring Portuguese-language programming that leases studio and tower space from WXKS. Owned by the Langer Broadcasting Group, LLC and licensed to Natick, Massachusetts with studios on 100 Mount Wayte Ave in Framingham;[97][98]

- WQOM (AM 1060) is an AM broadcasting station featuring business talk radio programming that leases studio and tower space from WXKS. Owned by the Langer Broadcasting Group, LLC and licensed to Ashland, Massachusetts with studios on 100 Mount Wayte Ave in Framingham;[97][99]

- WDJM-FM (91.3 FM) is Framingham State University's FM broadcasting station that features an open format with progressive rock, hip-hop, metal and electronic music. It is owned by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts and is licensed to Framingham, Massachusetts with studios at 100 State St. in Framingham;[100]

- Framingham Amateur Radio Association[101] is the local amateur radio enthusiasts group.

Film

In the spring of 2016, the town of Framingham was one of the settings for the film Patriots Day about the Boston Marathon bombing, starring Mark Wahlberg, John Goodman, Kevin Bacon, J.K. Simmons, Michelle Monaghan, Alex Wolff, Melissa Benoist and a cameo appearance by former athlete David Ortiz.[102] In spring 2009, Framingham was also used for the film The Company Men, starring Ben Affleck, Chris Cooper, Kevin Costner, and Tommy Lee Jones.[103]

Large parts of the film Don't Look Up, directed by Worcester, Massachusetts native Adam McKay and starring Academy Award winners Jennifer Lawrence, Leonardo DiCaprio and Meryl Streep, were shot in Framingham.

Points of interest

Framingham features dozens of athletic fields and civic facilities spread throughout the city in schools and public parks.[104] Many of the recreational facilities were constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the New Deal.

Culture

- Amazing Things Arts Center[105]

- Framingham Community Theater[106]

- Framingham History Center (formerly the Framingham Historical Society and Museum)[84]

- Danforth Museum[107]

- Metrowest Youth Symphony Orchestra[108]

- Pike Haven Homestead was built in 1693 by Jeremiah Pike. He and his descendants were town and militia officers, yeomen, and makers of spinning wheels in the colonial period. This house had been occupied by the same family for eight generations.[109]

Parks

- Bowditch Field is Framingham's main athletic facility. It is on Union Avenue midway between Downtown and Framingham Center and was the main athletic facility for the town. It houses a large multi-purpose football stadium that included permanent bleachers on both sides of the field. There is still a baseball field, tennis courts, a track and field practice area, and the headquarters of the city Parks Department. Bowditch, along with Butterworth and Winch Parks, were all built during the Great Depression of the 1930s as WPA projects. It underwent a complete renovation/reconstruction in 2010. It is also the current site of Framingham High's graduation ceremony.[110][111]

- Butterworth Park is at the corner of Grant St and Arthur St. The park occupies a square block near downtown. The park has a baseball stadium that includes permanent bleachers on one side of the field, a basketball court and a tennis court. There is street parking on three sides. The bleachers have since been taken down.

- Winch Park is the sister park to Butterworth and is in Saxonville next to the Framingham High School. It includes a baseball stadium that includes permanent bleachers on one side of the field, a basketball court, tennis courts and two large practice fields used for football, soccer and lacrosse. There are two additional multi-use fields on the other side of the high school's gymnasium building.

- Callahan State Park is a large state park run by the DCR located in North Framingham in the city's northwest corner.[112]

- Cochituate State Park on Lake Cochituate has a small section in Framingham where Saxonville Beach is on the north western shore of the lake.[113]

- Danforth Park on Danforth Street, not far from the Wayland town line. The small park has playground with a half basketball court and a small baseball/kickball field.

- Framingham Common is in Framingham Center in front of the old Town Hall along Edgell Road and Vernon Street. It features an outdoor stage for concerts and other fair weather events. It is a favorite of the students of Framingham State University, and the site of their annual graduation ceremonies.[114]

- Cushing Park on the South Side is a passive recreational area. The Framingham Peace and 9/11 Memorials are within the park across the street from Farm Pond, along with the Cushing Chapel. During World War II, the United States War Department constructed the Cushing General Hospital (named for Dr. Harvey Cushing) on this site; the chapel was part of the hospital complex. After the Korean War the hospital was sold to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for use as a geriatric hospital. After the hospital was closed in 1991, the land was converted into a 57-acre public park.[115][116][117]

- Long Athletic Complex On the south side of Framingham, near downtown the complex is the host of three little league baseball diamonds (Carter, Tusconi, Merloni), two Babe Ruth baseball fields (one being Long field), a softball field, outdoor basketball court, and two concession stands. The complex is surrounded by Keefe Tech High School, Loring Arena, and Barbari Elementary School. All of the fields have lights, and they host almost all of Framingham's Little League games. Long field is the host of JV high school games as well as most Framingham Babe Ruth games. The concession stands are both non-profit and all the money goes to the Framingham baseball league.

Conservation land

- Framingham has about 400 acres (1.6 km2) of land that has been placed into public conservation.[118]

- The Wittenborg Woods was donated to the town in 1999 by Harriet Wittenborg. The properties were originally purchased from Henry Ford in the 1940s. Henry Ford owned all of the land around the Wayside Inn in nearby Sudbury, and Harriet (and her husband) were required to interview with Mr. Ford to determine if they would be good stewards of the land.[119]

- The Morency Woods is a parcel of land that is physically located in Natick, Massachusetts on the Framingham border, but which is owned by the City of Framingham. This forested land was used as a sewer bed up until the mid-1940s and was placed into conservation in 2001.[120]

- The Sudbury Valley Trustees has approximately 200 acres (0.8 km2) of land in North Framingham and along the Sudbury River in a private conservation trust.[121]

Recreation

- Garden in the Woods, operated by the New England Wild Flower Society,[122] is a botanical garden that features the largest landscaped collection of native wildflowers in New England. It is in Nobscot, off of Hemenway Road.

- Framingham Country Club, along Salem End Road on the South Side, is a private club that features an 18-hole course with 6,580 yards (6,017 m) of golf from the longest tees for a par of 72.

- Millwood Farms Golf Course off Millwood Street was a public 14-hole, par 53 golf course. Originally a 9-hole course, it was expanded to 14 holes in the late 1970s. Attempts to purchase land for a full 18-hole were unsuccessful. Millwood Farms Golf Course was closed in 2018 to make way for a new housing development.

- Nobscot Scout Reservation is a private facility owned by the Knox Trail Council[123] of the Boy Scouts of America and is open to the public during most of the year.

- The city has several public beaches including Saxonville beach on Lake Cochituate, Washakum Beach on Lake Washakum, and the beach at Learned Pond.

- The former Cushing hospital grounds serve as walking, biking, rollerblading, and picnic areas.

- Farm Pond in South Framingham once used to host Fourth of July Fireworks, now is a picnic area.

- Edward F. Loring Skating Arena,[124] near Farm Pond at the corner of Fountain and Dudley Roads, is a municipal skating arena for area groups on a rental basis and public skating and stick time is available September through April.

- The Cochituate Rail Trail is a 3.6 mile, multi-use trail for walkers, joggers and bikers that runs from the Village of Saxonville in Framingham to Natick Center. While the Framingham section opened in 2015, the entire length of the trail opened to the public in 2021.[125][126]

Notable people

Politics

- Crispus Attucks, killed in the Boston Massacre[127][128]

- Deborah D. Blumer, Massachusetts State Representative for Framingham (2001–2006)

- Mary Beth Cahill, campaign manager for John Kerry's bid for presidency

- Josephine Collins, Suffragist; member of the National Woman's Party

- Jack Patrick Lewis, Massachusetts State Representative for 7th Middlesex District (2017–present)

- Robert Owens, Massachusetts State Representative and businessman

- Maria Robinson, Massachusetts State Representative for 6th Middlesex District (2019–present)

- Adam Schiff, U.S. Representative for California

- Yvonne M. Spicer, first black Mayor of Framingham and the first African-American woman to be popularly elected mayor in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

- Josiah Trowbridge, former Mayor of Buffalo, New York

Sports

- Blake Bellefeuille, NHL forward

- David Blatt (born 1959), Israeli-American basketball player and coach (most recently, for the Cleveland Cavaliers)

- Ron Burton, former NFL running back for the Boston Patriots, 1960 to 1965

- Carl Corazzini, NHL Hockey Player, Boston Bruins, Chicago Blackhawks, Detroit Red Wings, Edmonton Oilers

- Rich Gedman, former Major League Baseball catcher for the Boston Red Sox, 1980 to 1990

- Toby Kimball, NBA player for the Boston Celtics, San Diego Rockets, Milwaukee Bucks, Kansas City Kings, Philadelphia 76ers, and the New Orleans Jazz[129]

- Lou Merloni, Major League Baseball player for the Boston Red Sox, 1998 to 2003

- Kevin Nee, professional Strongman, youngest man ever to become professional Strongman

- Danny O'Connor, American professional boxer in the Light Welterweight division

- Tal Smith, baseball executive, former General Manager of the Houston Astros

- R. J. Brewer, pro wrestler

- Mark Sweeney, Major League Baseball player

- Pie Traynor, former Major League Baseball player, now in the Major League Baseball Hall of Fame

Arts and sciences

- Dave Amato, current guitarist for REO Speedwagon

- Ezra Ames (1768–1836), portrait painter in the 18th–19th centuries[130]

- Anthony Barbieri, comedy writer

- Daniel Belknap (1771–1815), composer

- Michael J. Clouse, songwriter, music producer

- Nancy Dowd, Academy Award winning screenwriter for Coming Home (1978)

- Alexander Rice Esty (1826–1881), architect

- Ginger Fish, member of Marilyn Manson

- Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller, pioneering African-American in the field of psychology and Alzheimer's disease

- Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, prominent African-American sculptor and artist from the 1920s

- Greg F. Gifune, Novelist, Editor, Film Producer, born in Framingham

- Leila Goldkuhl, fashion model

- David Hayes, music director of The Philadelphia Singers, Director of Orchestral and Conducting Studies at Mannes College The New School for Music

- Esther A. Hopkins, chemist, environmental attorney, and Framingham selectwoman

- Amy Leventer, marine biologist, micropaleontologist, Antarctic researcher

- Og Mandino (1923–1996), author

- Joe Maneri (1927–2009), noted classical composer and jazz improviser

- Christa McAuliffe, teacher, astronaut killed in the Challenger disaster

- Jo Dee Messina, country music singer

- Gordon Mumma, composer

- Edward Lewis Sturtevant, botanist, scientist, author

- Nancy Travis, actress

- Rob Urbinati, stage director, playwright

Media

- Tom Caron, New England Sports Network baseball analyst

- Katie Nolan, ESPN

- Jordan Rich, WBZ (AM) radio host

Military

- Richard W. Higgins, pilot in the USAF

- Donald K. Muchow, Chief of Chaplains of the U.S. Navy

- John Nixon, General in the Continental Army during the American Revolution

- Peter Salem, Revolutionary War soldier

Religious

- Gerald Fitzgerald, Roman Catholic priest

- Paul S. Loverde, Retired Roman Catholic bishop of the Diocese of Arlington

- Charles Henry Parkhurst, clergyman and social reformer who broke Boss Tweed's Tammany Hall Democratic party political machine

- William A. Rice, Roman Catholic bishop in Belize

Sister cities

- Lomonosov, Russia[131]

- Governador Valadares, Brazil[132]

See also

- Places of worship in Framingham, Massachusetts

- List of mill towns in Massachusetts

References

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files (Massachusetts)". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- "Census - Geography Profile: Framingham town, Middlesex County, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- "Census 2020 Data for Massachusetts". University of Massachusetts Donahue Institute. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- "Recount confirms Framingham votes to become a city". Boston Herald. April 25, 2017. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- General Gage's Instructions, Boston: John Gill, 1779.

- Samuel Adams Drake, History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts (Boston: Estes & Lauriat, 1880), vol. 1, p. 443

- "Massachusetts Historical Society: Object Archive". Masshist.org. 1909-09-10. Archived from the original on 2010-12-29. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "New England's Largest Town Wants to Become a City". Framingham, MA Patch. March 28, 2016. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- "Yvonne Spicer sworn in as Framingham's first mayor - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Archived from the original on 2018-01-23. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (DP-1): Framingham town, Middlesex County, Massachusetts". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001): Framingham town, Middlesex County, Massachusetts". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2017 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates (DP03): Framingham town, Middlesex County, Massachusetts". American Factfinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- "Brazil - Brasil - BRAZZIL - News from Brazil - Brazilian Is Not Hispanic - Brazilian Culture - October 2003". Brazzil. Archived from the original on 2016-09-20. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- Joel Millman (February 16, 2006). "Immigrant groups put new spin on cleaning niche". The Wall Street Journal – via Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- "Migration and Refugee Services". Usccb.org. Archived from the original on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Immigration in the U" (PDF). Uml.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- Haddadin, Jim (April 25, 2017). "Framingham recount affirms vote to become city". Worcester Telegram. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- "Summary of Home Rule Charter | City of Framingham, MA Official Website". www.framinghamma.gov. Retrieved 2018-02-01.

- "Police". City of Framingham. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- "History: Timeline". Framingham.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Contact Information - Framingham (01000000)". Profiles.doe.mass.edu. 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Contact Us". Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-01.

- "Contact Information - South Middlesex Regional Vocational Technical (08290000)". Profiles.doe.mass.edu. 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Contact Information - Christa McAuliffe Charter Public (District) (04180000)". Profiles.doe.mass.edu. 2008-04-07. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- Department of Housing and Community Development

- "Changes to Transit Service in the MBTA district" (PDF). Transithistory.org. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "> Commuter Rail Maps and Schedules". MBTA.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Framingham". Massport. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Mitch Evich (February 1, 2007). "Framingham forms regional transit authority". Massachusetts Municipal Association. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Andrew J. Manuse (July 22, 2007). "Southborough-Marlborough "model" to be picked up by MetroWest transit authority". The MetroWest Daily News. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- "Maps – Park-and-Ride Lots". Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- "Framingham Park-and-Ride Lots" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 26, 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- "The Evolution of Other Stores and Plazas". Framingham/Natick Retail. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Shoppers' World Launches Mall Era". Mass Moments. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "From the Marshalls Mall to Bed Bath & Beyond". Framingham/Natick Retail. 2004-05-08. Archived from the original on 2016-03-15. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "From Caldor/CVS to Wal-Mart". Framingham/Natick Retail. 2004-05-08. Archived from the original on 2016-07-25. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- Justin Tardiff. "From Bradlees to Kohl's". Framingham/Natick Retail. Archived from the original on 2016-09-30. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "The Evolution of the Route 30 Mall". Framingham/Natick Retail. Archived from the original on 2016-11-18. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "From the Framingham Mall to Target". Framingham/Natick Retail. Archived from the original on 2016-03-15. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "From the NYNEX/Verizon Building to Lowe's Home Improvement Warehouse". Framinghamnatickretail.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "From the Natick Mall (1966) to the Natick Mall (1994), Natick (2006), Natick Mall (2007), and Natick Collection (2007)". Framingham/Natick Retail. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "The Evolution of Sherwood Plaza". Framingham/Natick Retail. Archived from the original on 2016-10-18. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "The Evolution of the Cloverleaf Mall". Framingham/Natick Retail. Archived from the original on 2016-07-25. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Bid Adieu Shoppers World | Framingham Views". Framingham.wordpress.com. 2007-01-13. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- https://www.tjx.com/contact [bare URL]

- "North America Offices | IDG".

- "Massachusetts | American Cancer Society".

- "Mathworks expansion erases Carling Brewery building in Natick". The MetroWest Daily News. Archived from the original on 2020-12-06. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- "Breyers' Framingham facility closes its doors". Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- "Former Framingham ice cream factory demolished for new fitness center". The MetroWest Daily News. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- "Framingham Online - Downtown Defined, Framingham Economic Development Strategic Plan". Framingham.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Route 126 Downtown Roadway Improvement Project". Town of Framingham. Archived from the original on July 11, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- Ameden, Danielle (September 28, 2012). "Roundabout or traffic lights for downtown Framingham". Metrowest Daily News. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- Petroni, Susan (23 April 2015). "Where to Expect Delays Due to Construction in Downtown Framingham". Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- "Framingham Downtown Revitalization". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- "Shopping Guide - Downtown Framingham". Framingham.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "MHC: Preservation Awards". Sec.state.ma.us. 2008-01-01. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Beals and Thomas Project Profile: The Arcade at Downtown Framingham, Framingham, MA". 2007-02-03. Archived from the original on 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "The Residences at Dennison Triangle on Framingham.com". Archived from the original on October 22, 2006.

- "Local Bus Schedule with maps of these Company HQs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 27, 2007.

- "Framingham MA New Toyota Dealer | Serving Natick & Marlborough". Bernardi Toyota. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Ford Framingham, MA | Great Sales on Ford Focus, Fusion & More". Framingham Ford. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 29, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Sheraton Framingham Hotel & Conference Center". Marriott International.

- "Residence Inn Boston Framingham". Marriott International.

- "Framingham Center, Massachusetts MA Community Profile: City Data, Resources, Demographics". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- "About FSU". Framingham.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- Fram Ingham (2009-09-02). "Historic Framingham: Boston & Worcester trolley". Historicframingham.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Rent the Village Hall". villagehallonthecommon.org. 2014-06-20. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Framingham History Center – History comes alive here!". Framinghamhistory.org. 2017-03-15. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Shopping Guide - Nobscot". Framingham.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Shopping Guide - Saxonville". Framingham.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Framingham Source - Your Best Source for Framingham News!". Framingham Source. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- "Framingham Source". Framinghamsource.com.

- "Framingham". Framingham.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "MetroWest Daily News, Framingham, MA: Local & World News, Sports & Entertainment in Framingham, MA". Metrowestdailynews.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Local & World News, Sports & Entertainment in Framingham, MA". The Framingham Tab. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Globe West - The Boston Globe". Boston.com. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Your Town Framingham". The Boston Globe. May 17, 2011.

- "A Semana - The Brazilian Newspaper | A Semana..." Archived from the original on August 19, 2006. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- "Gatepost". Framingham State University. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "WATCH CHARTER DEBATE REPEATS ON ACCESS FRAMINGHAM TELEVISION ON CABLE CHANNELS • RCN 3 • COMCAST 9 • VERIZON 43 – Public Access Television For and By Framingham Residents". Accessfram.tv. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "The Boston Radio Dial: WKOX(AM)". The Archives @ BostonRadio.org. February 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-16.

- "The Boston Radio Dial: WSRO(AM)". The Archives @ BostonRadio.org. February 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-16.

- "The Boston Radio Dial: WBIX(AM)". The Archives @ BostonRadio.org. February 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-16.

- WDJM staff (September 12, 2007). "WDJM 91.3 MySpace page". MySpace.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2007. Retrieved September 16, 2007.

- "Framingham Amateur Radio Assoc". Fara.org. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "'Patriots Day' Crew Filming Watertown Shootout, Boat Scenes In Framingham". CBS Boston. 19 April 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- Bob Tremblay (April 17, 2009). "Costner, Affleck in good 'Company' in Framingham". The MetroWest Daily News. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- "Framingham Parks & Recreation". Archived from the original on November 20, 2005. Retrieved 2005-10-04.

- "Amazing Things Amazing Things Arts Center Framingham". Amazingthings.org. 2014-05-18. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Framingham Community Theater". Archived from the original on February 23, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- "Danforth Art". Danforthmuseum.org. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Adventures in Tech, Wealth & Fulfillment". METYSO. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- Sign erected at the site (corner of Belknap Rd and Grove St) by Massachusetts Bay Colony Tercentenary Commission

- "Framingham's Bowditch Field renovation ready to kick off". The MetroWest Daily News. October 29, 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- "Bowditch Athletic and Cultural Complex | City of Framingham, MA Official Website". Framinghamma.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Callahan State Park". Archived from the original on March 31, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- "Cochituate State Park". Archived from the original on March 31, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- "Framingham State University". Framingham.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- Bergeron, Chris (2015), Historian chronicles story of Framingham's Cushing Hospital, The MetroWest Daily News

- Paganella, Nicholas (2014), Remembering Cushing Hospital, 70 years later, The MetroWest Daily News

- Ameden, Danielle (2015), Framingham: Fond memories for Cushing Hospital, The MetroWest Daily News

- "Public Lands of the Framingham, MA Conservation Commission". Archived from the original on May 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- "Wittenborg Woods, Framingham, MA Conservation Land". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- "Macomber, Framingham, MA Conservation Land". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- "Sudbury Valley Trustees". Archived from the original on May 1, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- "New England Wild Flower Society — New England Wild Flower Society". Newfs.org. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Knox Trail Council | BSA". Ktc-bsa.org. 2016-12-15. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Framingham Parks & Recreation". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- "Cochituate Rail Trail | Massachusetts Trails | TrailLink".

- https://www.facebook.com/crtrail/ [user-generated source]

- "Africans in America/Part 2/Crispus Attucks". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2017-03-25.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 22, 2005. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Toby Kimball Past Stats, Playoff Stats, Statistics, History, and Awards". Databasebasketball.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607–1896. Marquis Who's Who. 1967.

- "FLAME". framingham.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008.

- Mineo, Liz (October 22, 2007). "Brazilian delegation coming to MetroWest". The MetroWest Daily News. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

Further reading

- 1871 Atlas of Massachusetts. by Wall & Gray. Map of Massachusetts. Map of Middlesex County.

- Old USGS maps of Everett.

- Ballard, William, A Sketch of the History of Framingham, published 1827, 71 pages.

- Barry, William, History of Framingham, Massachusetts, published 1847, 456 pages.

- Drake, Samuel Adams (compiler), Volume 1 (A-H), Volume 2 (L-W), published 1879–1880. 572 and 505 pages. Framingham article by Rev. Josiah Howard Temple in volume 1 pages 435–453.

- Parr, James; Swope, Kevin A., Framingham Legends & Lore, History Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1-59629-565-0

External links

На других языках

[de] Framingham

Framingham ist eine Stadt im Middlesex County, Massachusetts. Sie hat bei einer Fläche von 68,5 km² 72.362 Einwohner (Stand 2020), liegt westlich von Boston und östlich von Worcester.- [en] Framingham, Massachusetts

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии