world.wikisort.org - USA

Helena (![]() listen; /ˈhɛlənə/) is the capital city of Montana and the county seat of Lewis and Clark County.[3]

listen; /ˈhɛlənə/) is the capital city of Montana and the county seat of Lewis and Clark County.[3]

Helena | |

|---|---|

State capital | |

|

from the top: skyline; Cathedral of Saint Helena; Montana State Capitol; Benton Avenue Cemetery; Original Montana Governor's Mansion; and Carroll College | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Queen City of the Rockies, The Capital City | |

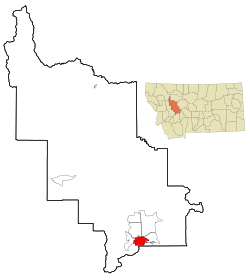

Location within Lewis and Clark County, Montana | |

Helena Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 46°35′28″N 112°1′13″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Montana |

| County | Lewis and Clark |

| Founded | October 30, 1864 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Wilmot Collins (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 16.90 sq mi (43.76 km2) |

| • Land | 16.86 sq mi (43.67 km2) |

| • Water | 0.04 sq mi (0.10 km2) |

| • Urban | 11 sq mi (30 km2) |

| Elevation | 3,875 ft (1,181 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 32,091 |

| • Density | 1,903.38/sq mi (734.91/km2) |

| • Metro | 83,058 |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (Mountain) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (Mountain) |

| ZIP code | 59601-02, 59626; 59604, 59620, 59624 (P.O. Boxes); 59623, 59625 (organizations) |

| Area code | 406 |

| FIPS code | 30-35600 |

| GNIS feature ID | 802116 |

| Waterways | Tenmile Creek |

| Website | www |

Helena was founded as a gold camp during the Montana gold rush, and established on October 30, 1864.[4] Due to the gold rush, Helena would become a wealthy city, with approximately 50 millionaires inhabiting the area by 1888. The concentration of wealth contributed to the city's prominent, elaborate Victorian architecture.[5][6]

At the 2020 census Helena's population was 32,091,[7] making it the fifth least populous state capital in the United States and the sixth most populous city in Montana.[8] It is the principal city of the Helena Micropolitan Statistical Area, which includes all of Lewis and Clark and Jefferson counties; its population is 83,058 according to the 2020 Census.[2]

The local daily newspaper is the Independent Record.[9] The city is served by Helena Regional Airport (HLN).[10]

History

Pre-settlement

The Helena area was long inhabited by various indigenous peoples.[11] Evidence from the McHaffie and Indian Creek sites on opposite sides of the Elkhorn Mountains southeast of the Helena Valley show that people of the Folsom culture lived in the area more than 10,000 years ago.[12] Before the introduction of the horse 300 years ago, and since, other native peoples, including the Salish and the Blackfeet, visited the area seasonally on their nomadic rounds.[13]

Early settlement and gold rush

By the early 1800s, people of European descent from the United States and British Canada began arriving to work the streams of the Missouri River watershed looking for fur-bearing animals such as the beaver, undoubtedly bringing them through the area now known as the Helena Valley.[14]

Gold strikes in Idaho Territory in the early 1860s attracted many migrants who initiated major gold rushes at Grasshopper Creek (Bannack) and Alder Gulch (Virginia City) in 1862 and 1863 respectively. So many people came that the federal government created a new territory called Montana in May 1864. The miners prospected far and wide for new placer gold discoveries. On July 14, 1864, the discovery of gold by a prospecting party known as the "Four Georgians" in a gulch off the Prickly Pear Creek led to the founding of a mining camp along a small creek in the area they called "Last Chance Gulch".[15][16][17][18][19]

By fall, the population had grown to over 200, and some thought the name "Last Chance" too crass. On October 30, 1864, a group of at least seven self-appointed men met to name the town, authorize the layout of the streets, and elect commissioners. The first suggestion was "Tomah," a word the committee thought had connections to the local Indian people. Other nominations included Pumpkinville and Squashtown[20] (as the meeting was held the day before Halloween). Other suggestions were to name the community after various Minnesota towns, such as Winona and Rochester, as a number of settlers had come from Minnesota. Finally, a Scotsman, John Summerville, proposed Helena, which he pronounced /həˈliːnə/ hə-LEE-nə,[21] in honor of Helena Township, Scott County, Minnesota. This immediately caused an uproar from the former Confederates in the room, who insisted upon the pronunciation /ˈhɛlɪnə/ HEL-i-nə, after Helena, Arkansas, a town on the Mississippi River. While the name "Helena" won, the pronunciation varied until approximately 1882 when the /ˈhɛlɪnə/ HEL-i-nə pronunciation became dominant. Later tales of the naming of Helena claimed the name came from the island of St. Helena, where Napoleon was exiled, or was that of a miner's sweetheart.[22][23]

Helena was surveyed by Captain John Wood in 1865 for the first time. The original streets of Helena followed the paths of miners, thus making the city blocks of Early Helena various sizes and shapes.[24]

In 1870, Henry D. Washburn, having been appointed Surveyor General of Montana in 1869, organized the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition in Helena to explore the regions that would become Yellowstone National Park.[25] Mount Washburn, within the park, is named for him. Members of the expedition included Helena residents:[26][27][28][29]

- Truman C. Everts, former U.S. Assessor for the Montana Territory

- Cornelius Hedges, U.S. Attorney of the Montana Territory

- Samuel T. Hauser, president of the First National Bank, Helena, Montana; later a Governor of the Montana Territory

- Warren C. Gillette, Helena merchant

- Walter Trumbull, son of U.S. Senator Lyman Trumbull (Illinois)

- Nathaniel P. Langford, then former U.S. Collector of Internal Revenue for Montana Territory. Langford helped Washburn organize the expedition and later helped publicize the remarkable Yellowstone region. In May 1872 after the park was established, Langford was appointed by the Department of Interior as its first superintendent.

Wealth boom

By 1888 about 50 millionaires lived in Helena, more per capita than in any city in the world.[30] They had made their fortunes from gold.[31] It is estimated about $3.6 billion in today's money was extracted from Helena during this period of time.[32] The Last Chance Placer is one of the most famous placer deposits in the western United States. Most of the production occurred before 1868. Much of the placer is now under Helena's streets and buildings.[33]

This large concentration of wealth was the basis of developing fine residences and ambitious architecture in the city; its Victorian neighborhoods reflect the gold years.[34] The numerous miners also attracted the development of a thriving red light district. Among the well-known local madams was Josephine "Chicago Joe" Airey, who built a thriving business empire between 1874 and 1893, becoming one of Helena's largest and most influential landowners.[35][36] Helena's brothels were a successful part of the local business community well into the 20th century, ending with the 1973 death of Helena's last madam, "Big Dorothy" Baker.[37][38]

Helena's official symbol is a drawing of "The Guardian of the Gulch", a wooden fire watch tower built in 1886. It still stands on Tower Hill overlooking the downtown district.[39] The tower, built in 1874, replaced a series of observation buildings, the original being built in response to a series of devastating fires that swept through the early mining camp.[40][41][42] On August 2, 2016, an arson attack severely damaged the tower and it was deemed structurally unstable. The tower is to be demolished but will be rebuilt using the same methods as in its original construction.[43][44]

In 1889, railroad magnate Charles Arthur Broadwater opened his Hotel Broadwater and Natatorium west of Helena.[45][46][47] The Natatorium was home to the world's first indoor swimming pool. Damaged in the 1935 Helena earthquake, it closed in 1941.[48][49][50] The property's many buildings were demolished in 1976.[51] Today, the Broadwater Fitness Center stands just west of the Hotel & Natatorium's original location, complete with an outdoor pool heated by natural spring water running underneath it.[52]

Helena has been the capital of Montana Territory since 1875 and the state of Montana since 1889. Referendums were held in 1892 and 1894 to determine the state's capital; the result was to keep the capitol in Helena. In 1902, the Montana State Capitol was completed.[53][54] Until the 1900 census, Helena was the most populous city in the state. That year it was surpassed by Butte (with a population of 30,470), where mining industry was developing.[55]

Among the settlers the city's prosperity attracted were Blacks fleeing racism in the South. Many found work in the mines or on the railroads and established a middle class that supported Black-owned businesses, Black churches, Black newspapers and a Black literary society. A Black police officer patrolled the town's wealthiest (white) neighborhood. But in the later 1900s new discriminatory laws, such as a ban on mixed marriages and the establishment of many sundown towns, along with the attendant racist attitudes that led to them drove many Blacks out not just Helena but the state, to the point that the city's Black population today is a small fraction of what it was in the early 20th century.[56]

In 1916, the United Daughters of the Confederacy commissioned the construction of the Confederate Memorial Fountain in Hill Park.[57] It was the only Confederate memorial in the Northwestern United States.[58] The fountain was removed on August 18, 2017, after the Helena City Commission deemed it a threat to public safety following a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.[59]

1980s–present

The Cathedral of Saint Helena[60] and the Helena Civic Center[61] are two of Helena's many significant historic buildings.

Many working Helenans (approx. 18%) work for agencies of the state government.[62] When in Helena, most people visit the local walking mall. It was completed in the early 1980s after Urban Renewal and the Model Cities Program in the early 1970s had removed many historic buildings from the downtown district.[63][64] During the next decade, a three-block shopping district was renovated that followed the original Last Chance Gulch. A small artificial stream runs along most of the walking mall to represent the underground springs that originally flowed above ground in parts of the Gulch.[65]

The Archie Bray Foundation, an internationally renowned ceramics center founded in 1952, is just northwest of Helena, near Spring Meadow Lake.[66]

A significant train wreck occurred on February 2, 1989, in which a 48-car runaway freight train slammed into a parked train near Carroll College, setting off an explosion that blasted out windows up to three miles away, causing most of the city to lose power and forcing some residents to evacuate in subzero weather.[67][68][69]

With the mountains, Helena has much outdoor recreation, including hunting and fishing.[70][71] Great Divide Ski Area is northwest of town near the ghost town of Marysville. Helena is also known for its mountain biking.[72] It was officially designated as an International Mountain Bicycling Association bronze level Ride Center on October 23, 2013.[73][74]

Helena High School[75] and Capital High School[76] are public high schools in Helena School District No. 1.

In 2017, Helena voters elected as mayor former Liberian refugee Wilmot Collins, who was widely reported to be Helena's first black mayor.[77][78] The Independent Record reported contested research indicating that in the early 1870s one E. T. Johnson, listed in the city directory as a black barber from Washington D.C., had been elected mayor, before Helena became an incorporated town.[79]

Geography

Helena is located at 46°35′45″N 112°1′37″W (46.595805, −112.027031),[80] at an altitude of 4,058 feet (1,237 m).[81]

Surrounding features include the Continental Divide, Mount Helena City Park, Spring Meadow Lake State Park, Lake Helena, Helena National Forest, the Big Belt Mountains, the Gates of the Mountains Wilderness, Sleeping Giant Wilderness Study Area, Bob Marshall Wilderness, Scapegoat Wilderness, the Missouri River, Canyon Ferry Lake, Holter Lake, Hauser Lake, and the Elkhorn Mountains.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 16.39 square miles (42.45 km2), of which 16.35 square miles (42.35 km2) is land and 0.04 square miles (0.10 km2) is water.[82]

Climate

Helena has a semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk), with long, cold and moderately snowy winters, hot and dry summers, and short springs and autumns in between.[83] Snowfall has been observed in every month but July, but is usually absent from May to September, and normally accumulates in only light amounts.[84] Winters have periods of moderation, partly due to warming influence from chinooks.[85] Precipitation mostly falls in the spring and is generally sparse, averaging only 11.4 inches (290 mm) annually.[86] The hottest temperature recorded in Helena was 105 °F (41 °C) on August 24, 1969 and July 15, 2002, while the coldest temperature recorded was −42 °F (−41 °C) on January 31, 1893, January 25, 1957 and February 2, 1996.[87]

| Climate data for Helena, Montana, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1880–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 63 (17) |

69 (21) |

78 (26) |

86 (30) |

95 (35) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

87 (31) |

76 (24) |

70 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 53.2 (11.8) |

55.6 (13.1) |

66.7 (19.3) |

76.6 (24.8) |

84.3 (29.1) |

91.9 (33.3) |

98.0 (36.7) |

97.1 (36.2) |

91.0 (32.8) |

79.0 (26.1) |

63.5 (17.5) |

53.0 (11.7) |

99.3 (37.4) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 32.4 (0.2) |

37.2 (2.9) |

47.5 (8.6) |

56.7 (13.7) |

66.4 (19.1) |

74.7 (23.7) |

86.1 (30.1) |

84.6 (29.2) |

73.3 (22.9) |

57.6 (14.2) |

42.8 (6.0) |

32.6 (0.3) |

57.7 (14.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 23.0 (−5.0) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

36.1 (2.3) |

44.5 (6.9) |

53.9 (12.2) |

61.7 (16.5) |

70.6 (21.4) |

68.8 (20.4) |

58.9 (14.9) |

45.5 (7.5) |

32.8 (0.4) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

45.5 (7.5) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 13.5 (−10.3) |

17.2 (−8.2) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

32.4 (0.2) |

41.5 (5.3) |

48.7 (9.3) |

55.1 (12.8) |

52.9 (11.6) |

44.6 (7.0) |

33.5 (0.8) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

14.2 (−9.9) |

33.4 (0.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −12.6 (−24.8) |

−5.3 (−20.7) |

4.0 (−15.6) |

18.4 (−7.6) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

37.2 (2.9) |

45.7 (7.6) |

42.0 (5.6) |

31.0 (−0.6) |

15.3 (−9.3) |

1.1 (−17.2) |

−8.8 (−22.7) |

−19.9 (−28.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −42 (−41) |

−42 (−41) |

−30 (−34) |

−10 (−23) |

17 (−8) |

30 (−1) |

36 (2) |

28 (−2) |

6 (−14) |

−8 (−22) |

−39 (−39) |

−40 (−40) |

−42 (−41) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.39 (9.9) |

0.42 (11) |

0.52 (13) |

1.02 (26) |

1.95 (50) |

2.21 (56) |

1.06 (27) |

1.04 (26) |

0.96 (24) |

0.78 (20) |

0.59 (15) |

0.46 (12) |

11.40 (290) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.6 (17) |

6.6 (17) |

4.6 (12) |

2.9 (7.4) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.2 (0.51) |

2.8 (7.1) |

5.4 (14) |

7.7 (20) |

37.2 (96.02) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 8.8 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 7.5 | 6.3 | 5.8 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 91.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.6 | 5.6 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 28.1 |

| Source 1: NOAA [86] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service [87] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 3,106 | — | |

| 1880 | 3,624 | 16.7% | |

| 1890 | 13,834 | 281.7% | |

| 1900 | 10,770 | −22.1% | |

| 1910 | 12,515 | 16.2% | |

| 1920 | 12,037 | −3.8% | |

| 1930 | 11,803 | −1.9% | |

| 1940 | 15,056 | 27.6% | |

| 1950 | 17,581 | 16.8% | |

| 1960 | 20,227 | 15.1% | |

| 1970 | 22,730 | 12.4% | |

| 1980 | 23,938 | 5.3% | |

| 1990 | 24,569 | 2.6% | |

| 2000 | 25,780 | 4.9% | |

| 2010 | 28,190 | 9.3% | |

| 2020 | 32,091 | 13.8% | |

| source:[88] U.S. Decennial Census[89][7] | |||

2010 census

As of the census of 2010,[90][91] there were 28,190 people, 12,780 households, and 6,691 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,724.2 inhabitants per square mile (665.7/km2). There were 13,457 housing units at an average density of 823.1 per square mile (317.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.3% White, 0.4% African American, 2.3% Native American, 0.7% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.6% from other races, and 2.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.8% of the population.[citation needed]

There were 12,780 households, of which 24.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.2% were married couples living together, 10.6% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 47.6% were non-families. 39.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 13.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older.[92] The average household size was 2.07 and the average family size was 2.77.[citation needed]

The median age in the city was 40.3 years. 20.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 11.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 23.3% were from 25 to 44; 29.5% were from 45 to 64; and 15.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.0% male and 52.0% female.[93]

2000 census

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

As of the census of 2000,[94] there were 25,780 people, 11,541 households, and 6,474 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,840.7 people per square mile (710.5/km2). There were 12,133 housing units at an average density of 866.3 per square mile (334.4/km2). The ethnic makeup of the city is 94.8% White, 0.2% African American, 2.1% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.4% from other races, and 1.7% from two or more races. 1.7% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 11,541 households, out of which 27.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 42.5% were married couples living together, 10.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.9% were non-families. 37.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.14 and the average family size was 2.83.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 22.4% under the age of 18, 11.1% from 18 to 24, 26.6% from 25 to 44, 26.0% from 45 to 64, and 13.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $34,416, and the median income for a family was $50,018. Males had a median income of $34,357 versus $25,821 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,020. About 9.3% of families and 14.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.4% of those under age 18 and 8.3% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Helena has a long record of economic stability with its history as being the state capital and being founded in an area rich in silver and lead deposits. However, this situation has resulted in a slow growing economy.[95][96][97] Its status as capital makes it a major hub of activity at the county, state, and federal level.[98] According to the Helena Area Chamber of Commerce, the capital's median household income is $50,889, and its unemployment rate stood at 3.8% in 2013, about 1.2% lower than the rest of the state.[99][100] Education is a major employer, with two high schools and accompanying elementary and middle schools for K–12 students as well as Helena College. Major private employers within the city of Helena include Carroll College and the medical community.[101][102]

Helena's economy is also bolstered by Fort William Henry Harrison, the training facility for the Montana National Guard, located just outside the city.[103] Fort Harrison is also home to Fort Harrison VA Medical Center, where many Helena-area residents work.[104]

Education

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

Higher education

- Carroll College, a Catholic liberal arts college which opened in 1909, enrolls 1,500 students.

- Helena College University of Montana, a two-year affiliate campus of The University of Montana, provides transfer, career, and technical education for more than 1,600 students. It opened in 1939.

Primary and secondary education

List of schools in Helena, Montana[105][106]

- Helena High School (1,674 students)

- Capital High School (1,416)

- C R Anderson Middle School (994)

- Helena Middle School (720)

- Four Georgians Elementary School (525)

- Rossiter Elementary School (445)

- Smith Elementary School (307)

- Warren Elementary School (267)

- Jim Darcy Elementary School (255)

- Bryant Elementary School (253)

- Broadwater Elementary School (253)

- Kessler Elementary School (211)

- St. Andrew School (162)

- Central School (The first public school in Helena)

- Jefferson Elementary School (250)

- Hawthorne Elementary School (245)

- East Valley Middle School

Library

Helena has a public library, a branch of the Lewis & Clark Library.[107]

Media

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2020) |

Helena's Designated Market Area is 205th in size, as defined by Nielsen Media Research, and is the fifth smallest media market in the nation.

- Newspapers

- Independent Record (daily, morning)

- Online news

- Montana Free Press (statewide news source)

- AM radio

- KKGR 680 (Oldies), KGR, LLC

- KCAP 950 (Talk), Cherry Creek Radio

- KROL 1430 (Classic Hits)

- FM radio

- KUHM 91.7 (National Public Radio), Montana NPR

- KQRV 96.9 (Country), Robert Cummings Toole

- KHGC 98.5 (Adult Contemporary), Cherry Creek Radio

- KBLL 99.5 (Country), Cherry Creek Radio

- KZMT 101.1 (Classic rock), Cherry Creek Radio

- KMXM 102.3 (Adult Contemporary), The Montana Radio Company, LLC

- KJPZ 104.1 (Christian), Hi-Line Radio Fellowship

- KMTX 105.3 (Adult Contemporary)

- Television

- KXLH-LD (CBS/MTN/Grit/Ion, channel 9)

- KUHM-TV (PBS, channel 10)

- KTVH-DT (NBC/CW/Cozi, channel 12)

- KHBB-LD (ABC/Fox, channel 21)

Notable people

- Josephine Airey, madam and landowner

- Stephen Ambrose, historian, author of Band of Brothers and Undaunted Courage

- Dorothy Baker, madam

- Max Baucus, former U.S. senator from Montana (1978-2014), and former U.S. Ambassador to China (2014-2017)[108]

- James Presley Ball, African-American daguerreotypist

- Jean Baucus, historian, author, and rancher

- Samuel Beall, Lieutenant Governor of Wisconsin

- Vice Admiral Donald Bradford Beary (1888–1966) (U.S. Navy), implemented Sea Replenishment during World War II

- Dirk Benedict, actor (The A-Team)

- Brand Blanshard, philosopher

- H. Kim Bottomly, former president of Wellesley College

- Isaac Brock, lead singer of Modest Mouse

- Mary Caferro, Montana state senator

- Thomas Henry Carter, United States senator from Montana[109]

- Lane Chandler, actor

- William H. Clagett, congressman from Montana Territory[110]

- Liz Claiborne, fashion designer[111]

- Wilmot Collins, first black mayor in Montana since statehood

- Kevin Michael Connolly, photographer

- Mike Cooney, Montana state senator and former Montana Secretary of State

- Gary Cooper, actor

- Margaret Craven, author

- Charles Donnelly, president of the Northern Pacific Railway

- Pat Donovan, Dallas Cowboys offensive tackle

- James Earp, saloonkeeper and brother of Wyatt Earp

- Truman C. Everts, Assessor of Internal Revenue for the Montana Territory between July 15, 1864, and February 16, 1870[112]

- Casey FitzSimmons, tight end with the Detroit Lions

- Cory Fong, Tax Commissioner of North Dakota

- John Gagliardi, College Football Hall of Fame coach

- Pat Gray, Host of Pat Gray Unleashed

- Tyler Knott Gregson, poet and author

- Russell Benjamin Harrison, son of President Benjamin Harrison and Indiana politician

- Rick Hill, congressman from Montana[113]

- Norman Holter, biophysicist and inventor of the Holter monitor

- Esther Howard, actress

- L. Ron Hubbard,[114] author and founder of Scientology

- Chuck Hunter, Montana state senator

- Hal Jacobson, member of Montana House of Representatives representing District 82

- Christine Kaufmann, Montana state senator

- Brian Knight, Major League Baseball umpire

- Nicolette Larson (1952-97), singer

- Nathaniel P. Langford, U.S. Collector of Internal Revenue (1864–69), Montana Territory, and first superintendent of Yellowstone National Park

- Dave Lewis, Montana state senator

- James F. Lloyd, congressman from California[115]

- Myrna Loy, actress

- Martin Maginnis, congressman from Montana Territory

- Tony Markellis, bassist and record producer

- Thomas Francis Meagher, Irish rebel, US Civil War brigadier general, Acting Governor of the Territory of Montana

- Dave Meier, Major League Baseball outfielder

- Colin Meloy, lead singer and songwriter of The Decemberists

- Maile Meloy, writer

- James C. Morton, actor

- Sean O'Malley, MMA fighter

- Bobby Petrino, current head football coach at Missouri State University

- Paul Petrino, current head football coach at the University of Idaho

- Charley Pride, country music singer

- Glenn Roush, Montana state legislator

- Henry H. Schwartz, chief of the U.S. General Land Office and U.S. senator from Wyoming[116]

- Leo Seltzer, creator of roller derby

- Vida Ravenscroft Sutton, playwright and radio professional

- George G. Symes, congressman from Colorado[117]

- Robert "Dink" Templeton, Olympic gold medalist in rugby

- Decius Wade, the "Father of Montana Jurisprudence"

- Thomas J. Walsh, U.S. senator from Montana[118]

- Henry D. Washburn, Surveyor General, Montana Territory, and commander of the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition to Yellowstone in 1870

- William F. Wheeler, U.S. Marshal, Civil War officer, Minnesota territorial Librarian and secretary to two governors, and founder of the Montana Historical Society, first in the West

- John Patrick Williams, former congressman from Montana[119]

- Belle Fligelman Winestine, writer and suffragist

- Molly Wood, executive editor at CNET.com

- Lt. General Samuel Baldwin Marks Young (U.S. Army), former Acting Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park[120]

- Dale L. Mortensen, member of Montana House of Representatives representing District 44

Gallery: modern day

- View of north face of Mount Helena and west side of city

- Mount Helena snowline (April 2005)

- Walking/biking trail between downtown and Mount Helena's peak

- View from Mount Helena's peak, accessible by bike and foot

Helena's Civic Center (Algeria Shrine Temple)

Helena's Civic Center (Algeria Shrine Temple)- Former Northern Pacific (aka Union) Depot, Helena Avenue

- View of Carroll College from Mount Helena

- A "Tour Train" on the walking mall that was designed during 1960s urban renewal

- Deer are common within the city limits

- The Guardian of the Gulch fire tower

Gallery: historical

- Main Street, 1860s

- An 1865 photograph taken from today's S. Park Ave., looking east

- The lynching of Arthur Compton and Joseph Wilson (1870)

- Banners from some of Helena's early newspapers

Cartographer's visualization — 1875

Cartographer's visualization — 1875 Cartographer's visualization — 1883

Cartographer's visualization — 1883 Cartographer's visualization — 1890

Cartographer's visualization — 1890- An 1891 image of the 1889 Power Building, named after magnate Thomas C. Power[121]

- Union Depot (later Northern Pacific Depot) ca. 1904

- Postcard of Main Street, 1900s (decade)

- View of Mount Helena from old high school, 1900s (decade)

Former Great Northern Depot, Neill Avenue (since replaced)

Former Great Northern Depot, Neill Avenue (since replaced)

References

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas". Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- "Helena Montana". Western Mining History. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Helena | Montana, United States". Encyclopedia Britannica. June 28, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Attardo, Pam (February 9, 2020). "Nuggets from Helena: The historic and architectural significance of Helena's Westside". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Vickers, Marques (September 30, 2017). The Golden Age of Helena Montana Architecture. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 5. ISBN 978-1977855060.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- "Biggest Cities In Montana". WorldAtlas. April 25, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Independent Record". Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "About". Helena Regional Airport. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Forest Prehistory". USDA Forest Service: Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020.

- MacDonald, Douglas H. (2012). Montana before history : 11,000 years of hunter-gatherers in the Rockies and Plains. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press Pub. Company. pp. 38–44. ISBN 9780878425853.

- Baumler, Ellen (2014). Helena, The Town That Gold Built: The First 150 Years. San Antonio, TX: HPNbooks. p. 28.

- Holmes, Krys (2008). "Chap. 5, Beaver, Bison, and Black Robes: Montana's Fur Trade, 1800-1860". Montana : stories of the land (PDF). Helena, MT: Montana Historical Society Press. pp. 80–89. Retrieved February 20, 2014.

- Baumler, Ellen (2014). Helena, The Town That Gold Built: The First 150 Years. San Antonio, TX: HPNbooks. pp. 6–7.

- "The city of Helena, Montana, is founded after miners discover gold". History.com. October 28, 2019. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "History of Helena - Catalog - Helena College". Helena College. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Bradbury, Mary Jane; Shields, Mike; Jacobson, Hal (January 3, 2018). "Nuggets from Helena: Reflecting on 153 years of Helena history". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020.

- Pardee, Joseph; Schrader, F.C. (1933). "Metalliferous deposits of the greater Helena mining region, Montana, USGS Bulletin 842" (PDF). USGS Publications Warehouse. USGS. p. 183. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- "History". Helena Area Chamber & Visitor Center. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Montana Pronunciation Guide". Billings Gazette. September 15, 2015. Archived from the original on August 31, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Palmer, Tom. "Naming Helena," Helena: The Town and the People, Helena, MT: American Geographic Publishing, 1987, pp 20, 22, 28-31

- "Helena Area Chamber of Commerce". Visit Montana. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Plat of the Town Site of Helena As entered at the U.S. Land Office. Lewis & Clarke Co. M.T. Drawn by A.F.L. August 7th 1882". Mining Maps and Views - Spotlight at Stanford. Archived from the original on July 19, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Yellowstone National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". U.S. National Park Service. September 17, 2019. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Yellowstone National Park - Plant and animal life". Encyclopedia Britannica. March 19, 2020. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Yellowstone Park established". History.com. February 27, 2020. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "The Superintendents -- Nathaniel Langford - Yellowstone National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". U.S. National Park Service. June 17, 2020. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment". United States National Park Service. February 27, 2020. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "50 facts from Montana history: #26". Great Falls Tribune. October 13, 2014. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "50 Millionaires Lived in Helena Because of Gold". American Profile. June 17, 2001. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "History of Helena - Catalog - Helena College". Helena College. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Boulter, George W (2010). "Placer Deposits of Last Chance Gulch, Helena, Montana" (PDF). Billings Geological Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2020 – via Datapages.

- "These 14 mansions offer a glimpse into Helena's cosmopolitan history". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. December 19, 2016. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Red Light District". Helena As She Was. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Corrigan, Terence (August 24, 2014). "The seedy side of Helena". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Wipf, Briana (November 1, 2014). "Upstairs girls leave mark on state". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Working girls". The Economist. February 29, 2008. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Guardian of the Gulch". Atlas Obscura. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Helena's Iconic Fire Tower". Helena As She Was. Archived from the original on January 6, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- Logan, Sean (January 20, 2014). "Fiery history: Several fires in Helena's early years helped shape the town". Missoulian. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Brant, Angela (July 5, 2010). "Guardian of the past". Billings Gazette. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- Chaney, Jesse (August 2, 2016). "Helena Fire Tower damaged in 'suspicious' blaze". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Friends of the Fire Tower: New nonprofit aims to restore and preserve Helena icon". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. March 19, 2018. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Charles A. Broadwater family papers, 1873-1928". researchworks.oclc.org. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Harmon's Histories: Join us for an evening at Col. Broadwater's magnificent resort". Missoula Current. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Inbody, Kristen (February 5, 2018). "A fourth chance for storied Helena hot springs". Great Falls Tribune. Archived from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Outdoor.com » Helena". Outdoor.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Broadwater Natatorium". Helena As She Was. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Chaney, Rob (March 4, 2018). "Hot springs book reveals long wet history of Montana soaks". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Broadwater Natatorium". Treasure State Lifestyles. April 1, 2015. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Broadwater History". Broadwater Hot Springs. Archived from the original on July 6, 2019. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- "Timeline of the Montana Capitol's History". Montana.gov. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020.

- "Montana Capitol Building timeline". Independent Record. July 6, 2002. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- 1900 United States Census. Washington, D.C.: United States Census Bureau. 1901. p. 461.

- Lang, William L. (April 1979). "The Nearly Forgotten Blacks on Last Chance Gulch, 1900-1912". Pacific Northwest Quarterly. University of Washington. 70 (2): 50–57. JSTOR 40489822. Retrieved June 3, 2021. Cited at Rothstein, Richard (2017). The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. New York: Liveright. pp. 41–42. ISBN 9781631494536.

- Knauber, Al (July 9, 2015). "Helena Confederate memorial draws debate at city commission meeting". Missoulian. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020.

- Bridge, Thom (July 4, 2015). "Helena officials to discuss Confederate memorial fountain". The Montana Standard. Butte, Montana. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- "City of Helena to remove Confederate fountain". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. August 16, 2017. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Corrigan, Terence (July 9, 2014). "Helena in 75 Objects: 3. Cathedral of St. Helena". Missoulian. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- Corrigan, Terrance (July 17, 2014). "Helena in 75 Objects: 11. Civic center spire". Missoulian. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- "Helena, MT". Data USA. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- "Walking Mall 1970s". Helena As She Was. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- "Helena in 75 Objects: 34. Downtown Walking Mall". Missoulian. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- "Greening Last Chance Gulch" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency. September 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- Loranger, Erin (December 13, 2017). "National Register recognizes Archie Bray Foundation as nationally significant". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Archived from the original on September 26, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- Brandt, Angela (February 2, 2009). "20 years ago today, Helena shook, rattled and froze". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Archived from the original on November 8, 2018.

- "Photos: Infamous 1989 train explosion remains one of Helena's worst disasters". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. February 2, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- "Photos: A train exploded next to Carroll College in 1989". Billings Gazette. February 5, 2019. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- "Fishing". United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service: Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020.

- "Hunting". United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service: Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest.

- Palmer, Denny K. (January 15, 2015). "Draft Desired Conditions Comments; Forest Plan Revision Helena and Lewis & Clark National Forests" (PDF). Montana Bicycle Guild. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 19, 2020.

- Madison, Erin (August 11, 2015). "Helena makes its mark as mountain bike destination". Great Falls Tribune.

- Lemon, Greg (August 15, 2015). "Helena earns recognition as mountain biking destination". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- "Search for Public Schools - School Detail for Helena High School". nces.ed.gov. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Search for Public Schools - School Detail for Capital High School". nces.ed.gov. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- Lister, Nolan. "Helena mayor, US Senate candidate found not guilty of leaving crash scene". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "In Montana, A Liberian Refugee Mounts A U.S. Senate Challenge". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- Bridge, Thom (November 8, 2017). "Will Helena's Wilmot Collins be Montana's first black mayor? Not exactly, historians say". Archived from the original on November 11, 2017.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Helena". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- "Helena, Mt Climate Helena, Mt Temperatures Helena, Mt Weather Averages". Climatemps.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- "Total of Snowfall (Inches)". wrcc.dri.edu. October 7, 2018. Archived from the original on October 8, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- "Montana Earth Science Picture of the Week". formontana.net. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved on August 22, 2022.

- "NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service. Retrieved on August 22, 2022

- Moffatt, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow, 1996, 131.

- "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- "2010 Census of Population and Housing" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- "Census.gov". Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- "Cities with the most female breadwinners". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- Johnson, Charles S. "Montana population migrating west, Census data shows". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- "Summary Population and Housing Characteristics, Montana: 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- Manning, Tyler. "Helena's economy continues slow growth as cost of living drops". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Deedy, Alexander. "Poised for growth: Helena's economy remains slow, but leaders optimistic". Billings Gazette. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Cates-Carney, Corin (January 29, 2020). "Montana Economic Slowdown Expected, Researchers Say". www.mtpr.org. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- "2019 Montana Economic Report" (PDF). University of Montana.

- "Helena Economy". Helena Area Chamber of Commerce.

- "Economic Trends" (PDF). Helena Area Chamber of Commerce.

- "Helena, MT". Data USA. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- Kirkpatrick, Maria. "Helena economy seeing growth in heath [sic] care and construction". Independent Record. Helena, Montana. Retrieved July 24, 2020.

- "Helena, Montana – Small Community Air Service Development Grant Application – April 2007" (PDF). AirlineInfo.com. Helena Regional Airport Authority. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- Chaney, Jesse. "Government jobs help stabilize Helena's housing market". Billings Gazette. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- "Schools in Helena, Montana". Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- "Economic Trends 2020". Helena Area Chamber of Commerce.f

- "Montana Public Libraries". PublicLibraries.com. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- "Max Baucus". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Thomas Henry Carter". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "William H. Clagett". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Fashion guru Liz Claiborne dies" Breaking News.ie, July 26, 2007

- "Yellowstone National Park: Its Exploration and Establishment Biographical Appendix". National Park Service. July 4, 2000. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- "Rick Hill". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Scientology Founder L. Ron Hubbard, Quote of the Week, Video Biography". Church of Scientology International. July 20, 2011. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- "James F. Lloyd". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Henry H. Schwartz". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "George G. Symes". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "Thomas J. Walsh". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- "John Patrick Williams". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved October 14, 2012.

- Kiki Leigh Rydell; Mary Shivers Culpin (2006). "Administration in Turmoil-Yellowstone's Management in Question 1907-1916". Managing the Matchless Wonders-History of Administrative Development in Yellowstone National Park, 1872-1965 YCR-CR-2006-03. National Park Service, Yellowstone Center for Resources. pp. 51–74.

- "The 1889 Power Building Popularly Known as the Power Block". Helena As She Was. 2010. Archived from the original on June 3, 2019.

Further reading

- Wood, Anthony. "After the West Was Won How African American Buffalo Soldiers Invigorated the Helena Community in Early Twentieth-Century Montana." Montana 66.3 (2016): 36–50.

External links

- Official website

- Vintage images on HelenaHistory.org

- "Helena, Montana". C-SPAN Cities Tour. November 2013.

![]() Helena travel guide from Wikivoyage

Helena travel guide from Wikivoyage

На других языках

[de] Helena (Montana)

Helena ist die Hauptstadt des US-Bundesstaats Montana. In der Region sind Bergbau und Landwirtschaft von großer Bedeutung, die Stadt ist heute das bedeutendste Handels- und Verwaltungszentrum von Montana. Helena ist der County Seat des Lewis and Clark County. Sehenswert sind vor allem das Kapitol mit einer Nachbildung der Freiheitsstatue, das Gemeindezentrum und die Kathedrale von Saint Helena des römisch-katholischen Bistums Helena.- [en] Helena, Montana

[ru] Хелена (Монтана)

Хе́лена[3][4], также Хели́на[5][6] (англ. Helena [ˈhɛlɨnə]) — город в США, столица штата Монтана и административный центр округа Льюис-энд-Кларк. Население — 32 091 человек (2020 год)[1].Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии

![An 1891 image of the 1889 Power Building, named after magnate Thomas C. Power[121]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/1891_Power_Block_building_-_Helena%2C_Montana.jpg/204px-1891_Power_Block_building_-_Helena%2C_Montana.jpg)