world.wikisort.org - USA

Bowling Green is a home rule-class city and the county seat of Warren County, Kentucky, United States.[2] Founded by pioneers in 1798, Bowling Green was the provisional capital of Confederate Kentucky during the American Civil War. As of the 2020 census, its population of 72,294[3] made it the third-most-populous city in the state, after Louisville and Lexington; its metropolitan area, which is the fourth largest in the state after Louisville, Lexington, and Northern Kentucky, had an estimated population of 179,240; and the combined statistical area it shares with Glasgow has an estimated population of 233,560.[4][5][6]

Bowling Green, Kentucky | |

|---|---|

City | |

Fountain Square Park, 2008 | |

Seal | |

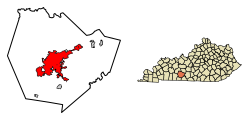

Location of Bowling Green in Warren County, Kentucky. | |

Bowling Green Location in the United States  Bowling Green Bowling Green (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 36°58′54″N 86°26′40″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kentucky |

| County | Warren |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Todd Alcott |

| Area | |

| • City | 40.65 sq mi (105.28 km2) |

| • Land | 40.39 sq mi (104.61 km2) |

| • Water | 0.26 sq mi (0.67 km2) |

| Elevation | 547 ft (167 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 72,294 |

| • Rank | Kentucky: 3rd |

| • Density | 1,789.81/sq mi (691.05/km2) |

| • Metro | 179,240 |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 42101-42104 |

| Area code(s) | 270 & 364 |

| FIPS code | 21-08902 |

| Website | www |

In the 21st century, it is the location of numerous manufacturers, including General Motors, Spalding, and Fruit of the Loom. The Bowling Green Assembly Plant has been the source of all Chevrolet Corvettes built since 1981. Bowling Green is also home to Western Kentucky University and the National Corvette Museum.

History

Settlement and incorporation

The first Europeans known to have reached the area carved their names on beech trees near the river around 1775. By 1778, settlers established McFadden's Station on the north bank of the Barren River.[7]

Present-day Bowling Green developed from homesteads erected by Robert[7] and George Moore and General Elijah Covington, the namesake of the town near Cincinnati.[citation needed] The Moore brothers arrived from Virginia circa 1794. In 1798, two years after Warren County had been formed, Robert Moore donated 2 acres (8,100 m2) of land to county trustees for the purpose of constructing public buildings. Soon after, he donated an additional 30 to 40 acres (120,000 to 160,000 m2) surrounding the original plot. The city of Bowling Green was officially incorporated by the Commonwealth of Kentucky on March 6, 1798.

Some controversy exists over the source of the town's name. The city refers to the first county commissioners' meeting (1798), which named the town "Bolin Green" after the Bowling Green in New York City, where patriots had pulled down a statue of King George III and used the lead to make bullets during the American Revolution.[7] According to the Encyclopedia of Kentucky, the name was derived from Bowling Green, Virginia, from where early migrants had come, or the personal "ball alley game" of founder Robert Moore.[8] Early records indicate that the city name was also spelled "Bowlingreen".

19th century

By 1810, Bowling Green had 154 residents. Growth in steamboat commerce and the proximity of the Barren River increased Bowling Green's prominence. Canal locks and dams on the Barren River made it much more navigable. In 1832, the first portage railway connected the river to the location of the current county courthouse. Mules pulled freight and passengers to and from the city on the tracks.

Despite rapid urbanization of the Bowling Green area in the 1830s, agriculture remained an important part of local life. A visitor to Bowling Green noted the boasting of a tavern proprietor named Benjamin Vance:

[Vance] says that he has seen a turnip this fall that measures thirty-two inches around, and has a beet that weighs sixteen pounds and a half;... that corn in this country grows so fast that if you look at it the next, it has grown a foot higher; that the "little hickory twigs" growing in the barrens have roots as large as his legs...

In 1859, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (currently CSX Transportation) laid railroad through Bowling Green that connected the city with northern and southern markets.

Bowling Green declared itself neutral in an attempt to escape the Civil War. Because of its prime location and resources, however, both the Union and Confederacy sought control of the city. The majority of its residents rejected both the Confederacy and the Lincoln administration. On September 18, 1861, around 1300 Confederate soldiers arrived from Tennessee to occupy the city, placed under command of Kentucky native General Simon Bolivar Buckner. The city's pro-Union feelings surprised the Confederate occupiers.[9] The Confederates fortified surrounding hills to secure possible military approaches to the valuable river and railroad assets. In November 1861, the provisional Confederate government of Kentucky chose Bowling Green as its capital.[10]

On February 14, 1862, after receiving reports that Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River had both been captured by Union forces under Ulysses S. Grant, the Confederates began to withdraw from Bowling Green. They destroyed bridges across the Barren River, the railroad depot, and other important buildings that could be used by the enemy. The city was subject to disruptions and raids throughout the remainder of the war. During the summer of 1864, Union General Stephen G. Burbridge arrested 22 civilians in and around Bowling Green on a charge of treason. This incident and other harsh treatment by federal authorities led to bitterness toward the Union among Bowling Green residents and increased sympathies with the Confederacy.

After the Civil War, Bowling Green's business district grew considerably. Previously, agriculture had dominated the city's economy. During the 1870s, many of the historic business structures seen today were erected. One of the most important businesses in Bowling Green of this era was Carie Burnam Taylor's dress-making company. By 1906, Taylor employed more than 200 women.

In 1868, the city constructed its first waterworks system. The fourth county courthouse was completed in 1868. The first three were completed in 1798, 1805, and 1813. In 1889, the first mule-drawn street cars appeared in the city. The first electric street cars began to replace them by 1895.

The Sisters of Charity of Nazareth founded St. Columbia's Academy in 1862, succeeded by St. Joseph's School in 1911.[11] In 1884, the Southern Normal School, which had been founded in 1875, moved to Bowling Green from the town of Glasgow, Kentucky. Pleasant J. Potter founded a women's college in Bowling Green in 1889. It closed in 1909 and its property was sold to the Western Kentucky State Normal School (see below, now known as Western Kentucky University). Other important schools in this era were Methodist Warren College, Ogden College (which also became a part of Western Kentucky University), and Green River Female College, a boarding school.

20th century

In 1906, Henry Hardin Cherry, the president and owner of Southern Normal School, donated the school to the state as the basis of the Western State Normal School. The school trained teachers for the expanding educational needs of the state. This institution is now known as Western Kentucky University and is the second-largest public university in the state, having recently surpassed the University of Louisville.

In 1906, Doctors Lillian H. South, J. N. McCormack, and A.T. McCormack opened St. Joseph Hospital to provide medical and nursing care to the residents and students in the area.[12][13]

In 1925, the third and last Louisville and Nashville Railroad Station was opened. About 27 trains arrived daily at the depot. Intercity bus lines were also a popular form of travel. By the 1960s, railroad travel had dramatically declined in the face of competition from airlines and automobiles. The station has been adapted for use as a museum.

In 1940, a Union Underwear factory built in Bowling Green bolstered the city's economy significantly. During the 1960s, the city's population began to surpass that of Ashland, Paducah, and Newport.

Downtown streets became a bottleneck for traffic. In 1949, the U.S. Route 31W Bypass was opened to alleviate traffic problems, but it also drew off business from downtown. The bypass grew to become a business hotspot in Bowling Green. A 1954 advertisement exclaimed, "Your business can grow in the direction Bowling Green is growing – to the 31-W By-Pass".

By the 1960s, the face of shopping was changing completely from the downtown retail square to suburban shopping centers. Between May and November 1967, stores in Bowling Green Mall opened for business. Another advertisement said, "One-stop shopping. Just park [free], step out and shop. You'll find everything close at hand." Between September 1979 and September 1980, stores in the larger Greenwood Mall came on line. The city's limits began to stretch toward Interstate 65.

By the late 1960s, Interstate 65, which runs just to the east of Bowling Green, was completed. The Green River Parkway (now called the William H. Natcher Parkway), was completed in the 1970s to connect Bowling Green and Owensboro. These vital transportation arteries attracted many industries to Bowling Green.

In 1981, General Motors moved its Chevrolet Corvette assembly plant from St. Louis, Missouri, to Bowling Green. In the same year, the National Corvette Homecoming event was created: it is a large, annual gathering of Corvette owners, car parades, and related activities in Bowling Green. In 1994, the National Corvette Museum was constructed near the assembly plant.

In 1997, Bowling Green was designated a Tree City USA by the National Arbor Day Foundation.

21st century

In 2012, the city undertook a feasibility study on ways to revitalize the downtown Bowling Green area. The Downtown Redevelopment Authority was formed to plan redevelopment. Plans for the project incorporated Bowling Green's waterfront assets, as well as its historic center and streetscape around Fountain Square. It also proposed a new building for the Bowling Green Area Chamber of Commerce, construction of a Riverwalk Park where downtown borders the Barren River, creation of a new public park called Circus Square, and installation of a new retail area, the Fountain Square Market.[14]

As of spring 2009, the new Chamber of Commerce, Riverwalk Park, and Circus Square have been completed. The Southern Kentucky Performing Arts Center, a facility for arts and education, broke ground in October 2009 and celebrated its opening night on March 10, 2012, with a concert by Vince Gill.[15] Ground was broken for the Fountain Square Market in 2012.

In 2005, an effort was made to incorporate a Whitewater Park into the downtown Bowling Green riverfront at Weldon Peete Park. Due to the recession, the project was not funded.

In 2011, the Bowling Green Riverfront Foundation expanded its efforts to develop land on the opposite side of Barren River from Mitch McConnell Park (which is located alongside the U.S. 31-W Bypass and the riverbank, between Louisville Road and Old Louisville Road), upriver to Peete Park. The new plans include use of the adjacent river for white-water sports—the stretch of river includes rapids rated on the International Scale of River Difficulty between Class II and Class IV—as well as a mountain biking trail, a bicycle pump track, and a rock climbing area.[16] Some of this facility will be located on a reclaimed landfill, which had served as Bowling Green's garbage dump for many years.

In 2014, Forbes magazine listed Bowling Green as one of the Top 25 Best Places to Retire in the United States.[17]

2021 Tornadoes

During the early morning hours of December 11, 2021, two destructive tornadoes struck Bowling Green. The first was an EF 3;tornado that heavily damaged or destroyed several buildings and homes and killed seventeen people.[18] The second tornado caused additional damage on the southern and eastern part of the city and was rated EF2.[19]

Geography

The Bowling Green-Warren County Regional Airport is 547 feet (167 m) above sea level. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 35.6 square miles (92 km2), of which 35.4 square miles (92 km2) is land and 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2) (0.45%) is covered by water.

Climate

Bowling Green has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa). The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 35.7 °F (2.1 °C) in January to 78.7 °F (25.9 °C) in July. On average, 41 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs occur annually, and 11 days occur each winter when the high fails to rise above freezing. Annual precipitation is 47.51 in, with spring being slightly wetter; snowfall averages 8.4 inches (21.3 cm) per year. Extreme temperatures range from −21 °F (−29 °C) on January 23 and 24, 1963, up to 108 °F (42 °C) on July 28, 1930.

| Climate data for Bowling Green, Kentucky (Warren County Airport), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 78 (26) |

82 (28) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

100 (38) |

110 (43) |

113 (45) |

110 (43) |

105 (41) |

98 (37) |

88 (31) |

78 (26) |

113 (45) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 46.2 (7.9) |

51.0 (10.6) |

60.1 (15.6) |

70.7 (21.5) |

78.7 (25.9) |

86.6 (30.3) |

89.7 (32.1) |

89.3 (31.8) |

83.0 (28.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

59.2 (15.1) |

49.4 (9.7) |

69.7 (20.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 37.2 (2.9) |

41.1 (5.1) |

49.2 (9.6) |

59.0 (15.0) |

68.0 (20.0) |

76.1 (24.5) |

79.7 (26.5) |

78.5 (25.8) |

71.4 (21.9) |

60.0 (15.6) |

48.4 (9.1) |

40.5 (4.7) |

59.1 (15.1) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 28.3 (−2.1) |

31.1 (−0.5) |

38.3 (3.5) |

47.3 (8.5) |

57.2 (14.0) |

65.6 (18.7) |

69.7 (20.9) |

67.7 (19.8) |

59.9 (15.5) |

48.0 (8.9) |

37.6 (3.1) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

48.5 (9.2) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−20 (−29) |

−6 (−21) |

19 (−7) |

30 (−1) |

39 (4) |

46 (8) |

42 (6) |

33 (1) |

19 (−7) |

−7 (−22) |

−14 (−26) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.64 (92) |

4.07 (103) |

4.54 (115) |

4.81 (122) |

5.03 (128) |

4.51 (115) |

4.28 (109) |

3.89 (99) |

3.64 (92) |

3.63 (92) |

3.73 (95) |

4.35 (110) |

50.12 (1,273) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 3.3 (8.4) |

3.3 (8.4) |

1.1 (2.8) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.2 (3.0) |

9.1 (23) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.3 | 10.7 | 11.9 | 11.6 | 11.8 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 8.8 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 11.5 | 126.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.1 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 6.5 |

| Source: NOAA (snow 1981–2010)[20][21][22] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 41 | — | |

| 1810 | 154 | 275.6% | |

| 1830 | 821 | — | |

| 1870 | 4,574 | — | |

| 1880 | 5,114 | 11.8% | |

| 1890 | 7,803 | 52.6% | |

| 1900 | 8,226 | 5.4% | |

| 1910 | 9,173 | 11.5% | |

| 1920 | 9,638 | 5.1% | |

| 1930 | 12,348 | 28.1% | |

| 1940 | 14,585 | 18.1% | |

| 1950 | 18,347 | 25.8% | |

| 1960 | 28,338 | 54.5% | |

| 1970 | 36,705 | 29.5% | |

| 1980 | 40,450 | 10.2% | |

| 1990 | 40,641 | 0.5% | |

| 2000 | 49,296 | 21.3% | |

| 2010 | 58,067 | 17.8% | |

| 2020 | 72,294 | 24.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23] | |||

As of the census[24] of 2010, 58,067 people and 22,735 households resided in the city. The population density was 1,631.1 inhabitants per square mile (629.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 75.8% White, 13.9% African American, 0.3% Native American, 4.2% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 2.16% from other races, and 2.7% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 6.5% of the population.

Of the 22,735 households, 24.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.1% were married couples living together, 14.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 48.3% were not families. About 35.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 19.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.28, and the average family size was 2.99.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 20.1% under the age of 18, 28% from 15 to 24, 25.6% from 25 to 44, 18.8% from 45 to 64, and 10.6% who were 65 or older. The median age was 27.6 years. Females made up 51.7% of the population and males made up 48.3%.

The median income for a household in the city was $33,362, and for families was $45,287. Males had a median income of $35,000 versus $28,916 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,302. About 19.4% of families and 27.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 30.9% of those under age 18.

Economy

Bowling Green is shifting to a more knowledge-based, technology-driven economy. With one major public university and a technical college, Bowling Green serves as an education hub for the south-central Kentucky region. In addition, the city is the region's leading medical and commercial center.

General Motors Manufacturing Plant, Holley Performance Products, Houchens Industries, SCA, Camping World, Kobe Steel, Minit Mart, Fruit of the Loom, Russell Brands, and other major industries call Bowling Green home. It has also attracted new industries, such as Bowling Green Metalforming, a division of Magna International, Inc., and Halton Company, which chose to expand their worldwide companies into Bowling Green.

Commonwealth Health Corporation, Western Kentucky University, and Warren County Board of Education are the biggest employers for Bowling Green and the surrounding region. Other companies based in Bowling Green include Eagle Industries and Trace Die Cast. The third-largest home shopping network, EVINE Live, has its warehouse fulfillment center located off Nashville Road. EVINE Live also recently moved a large amount of its customer service call center operations to its Bowling Green location. EVINE Live's corporate headquarters are located in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, although the largest part of its day-to-day operations are in Bowling Green.

Compared with Elizabethtown and Owensboro MSAs, Bowling Green has experienced the largest post-recession employment gain. From November 2001 to April 2006, total payroll employment increased by 13%. Bowling Green has experienced a 5% increase in manufacturing employment, a 5% increase in professional and business services, and a 6% increase in leisure and hospitality since April 2005.

Bowling Green's high income and job growth combined with a low cost of doing business led the city to be named to Forbes magazine's 2009 list of the "Best Small Places for Business". In an evaluation of 179 cities across the nation, Forbes ranked Bowling Green 19th best city in which to do business, finishing ahead of Elizabethtown and Owensboro. The list ranked Bowling Green 34th nationwide for the lowest cost-of-living and 22nd for highest job growth.

In March 2009, the Bowling Green metropolitan area was recognized by Site Selection magazine as a top economic development community in the United States for communities with populations between 50,000 and 200,000 people. The Bowling Green metro also received the same recognition by Site Selection in 2008.

The Bowling Green Area Chamber of Commerce received the 2009 Chamber of the Year by the American Chamber of Commerce Executives and a 5-Star Chamber by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Top employers

According to the city's 2019 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[25] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Western Kentucky University | 4,114 |

| 2 | Commonwealth Health Corporation | 2,934 |

| 3 | BG Metalforming LLC | 1,297 |

| 4 | Union Underwear Co. LLC | 1,218 |

| 5 | Warren County Public Schools | 1,125 |

| 6 | Graves-Gilbert Clinic PSC | 1,016 |

| 7 | NS Food Group Inc | 971 |

| 8 | Henkel Consumer Goods Inc | 930 |

| 9 | General Motors Corporation | 887 |

| 10 | Kentucky State Treasurer | 779 |

Arts and culture

Museums

- Kentucky Museum and Library – Home of rich collections and education exhibits on Kentucky history and heritage. Genealogical materials, published works, manuscripts and folk life information.

- National Corvette Museum – Showcase of America's sports car with more than 75 Corvettes on display, including mint classics, one-of-a-kind prototypes, racetrack champions and more.

- Historic Railpark and Train Museum – L & N Depot – Train museum in the original train depot of Bowling Green. Opened after the library moved at the end of 2007. Includes 5 restored historic rail cars.

- Riverview at Hobson Grove – This historic house museum is a classic example of Italianate architecture—arched windows, deep eaves with ornamental brackets, and cupola. Painted ceilings. Began late 1850s, Confederate munitions magazine in winter 1861–62, and completed 1872.

Sports and event venues

E.A. Diddle Arena, located on the campus of Western Kentucky University, is a multi-purpose arena with a seating capacity of 7,500 persons. Built in 1963 and renovated in 2004, the arena has hosted college sports such as basketball and volleyball. It also hosted the KHSAA Girls' Sweet Sixteen state championship event in high school basketball from 2001 to 2015, after which it moved to BB&T Arena at Northern Kentucky University.[26] The arena has also played host to various traveling rodeos and circuses. In 2006, Diddle Arena hosted the first WWE event to be held in Bowling Green in over ten years.

The city and surrounding area is home to the Warren County Inline Hockey League. It also is home to the Western Kentucky University Hilltoppers team, which competes in the NCRHA, and has several members in the Bluegrass Hockey League and Central Commonwealth League.

Bowling Green Ballpark is a new stadium currently in use in Bowling Green. It is primarily used for baseball, for the High-A Bowling Green Hot Rods organization of the High-A East. The Hot Rods began play in the spring of 2009 in the South Atlantic League, transferring to the Midwest League for 2010. In 2021 as part of Minor League Baseball's realignment they began play in the newly formed High-A East. They are a farm team for Major League Baseball's Tampa Bay Rays.

The Bowling Green Hornets of the Central Basketball League are based in Bowling Green, although they play their home games in Russellville. The Hornets are coached by Russellville native Nathan Thompson.

Golf courses

Bowling Green has six golf and eight disc golf courses.

| Golf | Disc golf |

|---|---|

| Crosswinds | Basil Griffin Park |

| Paul Walker | Hobson Grove Park |

| River View | KOA Kampground |

| Olde Stone | Lovers Lane Park |

| Bowling Green Country Club | Preston Miller Park |

| Indian Hills | Spero Kereiakes Park |

| White Park | |

| William H. Natcher Elementary |

Other attractions

- Bowling Green Ballpark

- Beech Bend Park

- General Motors Assembly Plant

- National Corvette Homecoming

- Capitol Arts Center

- Cave Spring Caverns

- Eloise B. Houchens Center

- Historic Railpark at the L&N Depot

- Lost River Cave and Valley

- Riverview at Hobson Grove

- Great American Donut Shop (GADS)

- William H. Natcher Federal Building and United States Courthouse

- Southern Kentucky Performing Arts Center (SkyPac)

- Low Hollow Bike Trail at Weldon Peete Park

- Corsair Artisan Distillery

- Civil War Discovery Trail

- Duncan Hines Scenic Byway

- Shake Rag Historic District

- Warren County Quilt Trail

- St. Joseph Historic District

Parks and recreation

The Bowling Green Parks and Recreation Department administers 895 acres (3.62 km2) of public land for recreational use.

Community centers

- F. O. Moxley – Facility includes a game room (billiards, video games), board game room, concession stand, racquetball/wallyball courts and basketball courts.

- Parker-Bennett – Facility has hourly rental rates for meetings, parties and receptions.

- Kummer/Little Recreation Center – Facility includes basketball/volleyball courts, concession stand, and walking trails.

- Delafield Community Center – Facility includes an auditorium, basketball courts, a playground, and picnic shelters.

Parks

- See Parks in Bowling Green, Kentucky for a formatted table of this data.

Swimming centers

- Russell Sims Aquatic Center – The largest "water playground" in south-central Kentucky. The center includes zero-depth entry into the water, splash playground, swimming pool, water slides, diving boards and concessions.

- Warren County Aquatics Facility – Domed pool facility open year-round. Closed February 2008. New facility is now open on Lover's Lane behind Warren County Public Schools main office. This facility was closed to public in April 2014 and is now used by private and school swim teams and physical therapy.

Education

Primary and secondary education

Public education is provided by the Bowling Green Independent School District in inner sections of Bowling Green and by Warren County Public Schools in outerlying sections.[27] Several private schools also serve Bowling Green students.

Elementary schools

Warren County Public Schools

- Alvaton Elementary

- Briarwood Elementary

- Bristow Elementary

- Cumberland Trace Elementary

- Jennings Creek Elementary

- Jody Richards Elementary

- Lost River Elementary

- North Warren Elementary

- Oakland Elementary

- Plano Elementary

- Rich Pond Elementary

- Richardsville Elementary

- Rockfield Elementary

- Warren Elementary

- William H. Natcher Elementary

Bowling Green Independent School District

- Dishman-McGinnis

- Parker Bennett Curry

- Potter Gray

- T.C. Cherry

- W.R. McNeill

Middle and junior high schools

All of these schools are operated by the Warren County district except Bowling Green Junior High.

- Bowling Green Junior High

- Drakes Creek Middle School

- Henry F. Moss Middle School

- Warren East Middle School

- South Warren Middle School

High schools

All schools are operated by the Warren County district except Bowling Green High and Carol Martin Gatton Academy of Mathematics and Science.

- Bowling Green High

- Carol Martin Gatton Academy of Mathematics and Science in Kentucky

- Greenwood High

- Warren Central High

- Warren East High

- South Warren High School

- Lighthouse Academy High School

Religious Schools

- Legacy Christian Academy - Preschool through 12th grade [29]

- Foundation Christian Academy – Preschool through 12th grade Church of Christ Christian school

- Holy Trinity Lutheran – Preschool through 6th grade Lutheran Christian school[30]

- Old Union School – Preschool through 12th grade Christian school[31]

- Saint Joseph Interparochial School– Preschool through 8th grade Catholic school[32]

Postsecondary education

- Bowling Green Adult Learning Center

- Daymar College

- Southcentral Kentucky Community and Technical College

- Western Kentucky University

Public library

The Warren County Public Library has three permanent locations. The Main Library, which opened in 1956, is in downtown Bowling Green. The Smiths Grove Branch, the system's first branch, is located in the nearby community of Smiths Grove, Kentucky. The system's largest branch is the Bob Kirby Branch Library, located off Interstate 65 close to Greenwood High School, which opened spring 2008. The Graham Drive Community Library was a neighborhood branch located in a residential area of the Housing Authority of Bowling Green that opened in late 2007, replacing the branch formerly located in the Sugar Maple Square Shopping Center; it was replaced by a number of community "satellite library" locations in late 2020. The Mobile Branch, now retired, was a 28-foot (8.5 m) truck that traveled across Bowling Green and Warren County carrying a variety of library materials for adults and children. The Depot Branch, which opened in 2001, was located in the historic, renovated Louisville and Nashville Railroad Depot and housed a technology and early childhood center, as well as traditional library materials; it closed in late 2007. On July 27, 2007, the Warren County Fiscal Court voted to create a county-wide taxing district to benefit the public library. The library system, formerly known as the Bowling Green Public Library, became the Warren County Public Library on July 1, 2008.

Media

Print media

- The Amplifier – Arts & Entertainment monthly[33]

- Bowling Green Daily News[34]

- College Heights Herald – WKU student newspaper[35]

- Soky Happenings[36]

Television

Spectrum (Cable Operator)

- WDNZ Antenna TV Channel 11

- WBKO ABC Channel 13

- WKYU PBS Channel 24

- WCZU Court TV Channel 39

- WNKY NBC Channel 40

- WKGB PBS/KET Channel 53

Digital broadcast

- WDNZ Antenna TV Channel 11.1 720i

- WDNZ Stadium Channel 11.2 1080i

- WDNZ The Country Network Channel 11.3 480i

- WBKO ABC Channel 13.1 720p

- WBKO Fox Channel 13.2 480i

- WBKO CW Channel 13.3 480i

- WKYU PBS Channel 24.1 1080i

- WKYU Create Channel 24.2 480i

- WCZU Court TV Channel 39.1 480i

- WCZU Buzzr Channel 39.2 480i

- WCZU Bounce TV Channel 39.3 480i

- WCZU SBN Channel 39.4 480i

- WCZU GRIT Channel 39.5 480i

- WCZU Court TV Mystery Channel 39.6 480i

- WCZU Cozi TV Channel 39.7 480i

- WNKY NBC Channel 40.1 1080i

- WNKY CBS Channel 40.2 480i

- WNKY MeTV Channel 40.3 408i

- WKGB PBS Channel 53.1 KET1 720p

- WKGB PBS Channel 53.2 KET2 480i

- WKGB PBS Channel 53.3 KETKY The Kentucky Channel 480i

- WKGB PBS Kids Channel 53.4 480i

Radio

- AM 930 WKCT – News/Talk

- AM 1340 WBGN – The Ticket(Fox Sports Radio)

- AM 1450 WWKU – ESPN Radio

- FM 88.1 WAYFM – WAYFM

- FM 88.9 WKYU – Western Kentucky University Public Radio

- FM 90.7 WCVK – Christian Family Radio

- FM 91.7 WWHR – "Revolution" WKU's student radio station

- FM 93.3 WDNS – Bowling Green's Classic Rock Station

- FM 95.1 WGGC – Goober 95.1 – Country

- FM 96.7 WBVR – The Beaver – Country (licensed to Auburn, Kentucky)

- FM 100.7 WKLX – Sam 100.7 – Classic hits (licensed to Brownsville, Kentucky)

- FM 103.7 WHHT – Howdy 103.7 – Country (licensed to Cave City, Kentucky)

- FM 105.3 WPTQ – The Point – Classic / Active Rock (licensed to Glasgow, Kentucky)

- FM 106.3 WOVO – Wovo106.3 – Adult contemporary (licensed to Horse Cave, Kentucky)

- FM 107.1 WUHU – Woohoo – Top 40 (licensed to Smiths Grove, Kentucky)

Transportation

Major highways

Interstate 65 north to Louisville, Kentucky south to Nashville, Tennessee

Interstate 65 north to Louisville, Kentucky south to Nashville, Tennessee Interstate 165 north to Owensboro, Kentucky

Interstate 165 north to Owensboro, Kentucky U.S. Route 231 north to Morgantown, Kentucky south to Scottsville, Kentucky

U.S. Route 231 north to Morgantown, Kentucky south to Scottsville, Kentucky U.S. Route 31W north to Park City, south to Franklin, Kentucky

U.S. Route 31W north to Park City, south to Franklin, Kentucky

U.S. Route 68 / Kentucky State Route 80 west to Hopkinsville, Kentucky, east to Lexington, Kentucky / Somerset, Kentucky

U.S. Route 68 / Kentucky State Route 80 west to Hopkinsville, Kentucky, east to Lexington, Kentucky / Somerset, Kentucky

Other highways

Kentucky State Route 185

Kentucky State Route 185 Kentucky State Route 234

Kentucky State Route 234 Kentucky State Route 242

Kentucky State Route 242 Kentucky State Route 880

Kentucky State Route 880

Former highways

Kentucky State Route 67 (1929-1969)

Kentucky State Route 67 (1929-1969)- William H. Natcher Green River Parkway-KY-9007(Replaced by I-165, North to Owensboro, Morgantown, Beaver Dam, South to Bowling Green)

Air transport

The city is served by Bowling Green–Warren County Regional Airport.

Buses

Community Action of Southern Kentucky operates GO bg Transit, which provides public transportation within Bowling Green.

Bowling Green was served for many years by intercity bus carriers, primarily Greyhound. But with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Greyhound downgraded their existing station to an unmanned stop, and then eliminated the stop entirely in May 2020. The end of Greyhound service marked the first time the city has been without some form of public intercity transportation since 1858, when the Louisville and Nashville Railroad first reached the city.

Greyhound now serves a stop in Franklin, Kentucky, about 20 miles south of Bowling Green.

Tornado Bus Company, based in Mexico to primarily serve the Hispanic market, lists Bowling Green as a destination, but the stop is actually located in Smiths Grove, Kentucky, about 12 miles northeast of downtown Bowling Green.

Rail

Bowling Green receives rail freight service from CSX through the former Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) namesake line. The R.J. Corman Railroad Group operates freight service on the former L&N line to Memphis from Bowling Green to Clarksville, Tennessee; the line joins with CSX at Memphis Junction on Bowling Green's southern side.

Nearby cities and communities

County communities

Nearby communities include: Allen Springs, Alvaton, Blue Level, Browning, Cavehill, Drake, Oakland, Petros, Plano, Plum Springs, Richardsville, Rich Pond, Rockfield, Smiths Grove and Woodburn.

Neighboring cities

| Brownsville | Franklin | Glasgow |

| Morgantown | Russellville | Scottsville |

Notable people

- Thomas Lilbourne Anderson – U.S. Representative from Missouri[37]

- Ben Bailey – comedian and host of TV game show Cash Cab

- Gary Barnidge – professional football tight end for the Cleveland Browns

- Danny Julian Boggs – United States Circuit Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

- Sam Bush – musician

- Athena Cage – musician

- Cage the Elephant – rock band

- Chris Carmichael – musician

- John Carpenter – film director, producer, actor, screenwriter, and composer

- Rex Chapman – former professional basketball player, played for the Kentucky Wildcats in college, played professionally for the Charlotte Hornets, Washington Bullets, Miami Heat and the Phoenix Suns.

- David F. Duncan – epidemiologist and drug policy consultant in the Clinton Administration

- George Fant - Professional football offensive tackle for the Seattle Seahawks, played college basketball for the Western Kentucky Hilltoppers before pursuing football career.

- Frances Fowler – painter

- Foxhole – instrumental post-rock group

- Dorothy Grider – artist and illustrator of children's books

- Henry Grider – U.S. Representative

- Brett Guthrie – U.S. Representative

- Mordecai Ham – Christian evangelist and pastor of the Burton Memorial Baptist Church early in the 20th century

- Corey Hart – Milwaukee Brewers right fielder, 2008 and 2010 MLB All Star

- Duncan Hines – food critic and cookbook author

- Hillbilly Jim – professional wrestler

- Ben Keith – American pedal steel guitarist, solo musician and producer

- Paul Kilgus – former professional baseball player

- John D. Minton, Jr. – Chief Justice of the Kentucky Supreme Court

- Doug Moseley – former United Methodist clergyman and former state senator

- William Natcher - U.S. Representative from 1953 to 1994

- Thomas Nicholson – Professor at Western Kentucky University, drug abuse and drug policy expert

- Rand Paul – ophthalmologist and U.S. Senator; son of U.S. Representative Ron Paul from Texas

- Deborah Renshaw – former NASCAR driver

- Robert Reynolds – former professional football player

- Jody Richards – former Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives

- Nappy Roots – platinum album selling rap group

- Sleeper Agent – rock band

- Zachary Stevens – vocalist of the band Savatage

- Chris Turner – former professional baseball player

- David Bell - author

- Terry Taylor - Professional Basketball player for the Indiana Pacers

Sister cities

Bowling Green has one sister city, as designated by Sister Cities International:

Kawanishi, Japan

Kawanishi, Japan

See also

- Bowling Green massacre

- Kentucky Valkyries

- List of cities in Kentucky

References

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - City of Bowling Green. "Early History of Bowling Green". Accessed July 22, 2013.

- "Dictionary of Places: Bowling Green". Encyclopedia of Kentucky. New York City: Somerset Publishers. 1987. ISBN 0-403-09981-1.

- Baird, Nancy Disher; Carraco, Carol Crowe (1999). Bowling Green and Warren County: A Bicentennial History. Bowling Green, KY: Liberty Printing. p. 13. ISBN 978-0932017048.

- Kleber, John E., ed. (1992). "Confederate State Government". The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- "Saint Joseph School – Contact/Directions". Stjosephschoolbg.org. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- "Dr Lillian Herald South". Warren County Medical Society official website. Bowling Green, Kentucky: Warren County Medical Society. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- Kentucky State Medical Association. (1913). Kentucky Medical Journal. Louisville, Ky: The Kentucky State Medical Association. page 160. Accessed on 31 March 2010.

- "The District - Accomplishments". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- Archived March 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Bowling Green Riverfront Foundation". Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- William P. Barrett. "The Best Places To Retire In 2014". Forbes.

- NWS Damage Survey for 12/11/2021 Tornado Event (Report). Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Louisville, Kentucky. December 22, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- "NWS Damage Survey for 12/11/21 Tornado Event". Iowa Environmental Mesonet. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Louisville, Kentucky. December 22, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Station: Bowling Green Warren CO AP, KY". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Station: Bowling Green Warren CO Airport, KY". U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1981-2010). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "City of Bowling Green CAFR" (PDF). Bgky.org. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Board of Control Approves Future Championship Sites, Football Alignment" (Press release). Kentucky High School Athletic Association. May 12, 2014. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Warren County, KY" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- "List - Warren County Public Schools". www.warrencountyschools.org. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- "Legacy Christian Academy of Bowling Green". legacychristianacademybg.com. Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- Kenton Glass. "Home – Holy Trinity Lutheran School".

- "Welcome to Old Union School - Old Union School". Retrieved May 27, 2021.

- https://www.stjosephschoolbg.org/

- "The Amplifier Homepage". bgamplifier.com. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- "Bowling Green Daily News Homepage". bgdailynews.com. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- "College Heights Herald Homepage". wkuherald.com. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- "SOKY Happenings Homepage". sokyhappenings.com. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607-1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

Further reading

- Davis, William C., ed. (1990). Diary of a Confederate Soldier: John S. Jackman of the Orphan Brigade. American Military History. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 18–24. ISBN 0-87249-695-3. LCCN 90012431. OCLC 906557161.

- Hall, Eliza Calvert (October 1937). "Bowling Green and the Civil War". Filson Club History Quarterly. 11 (4). Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

External links

- Official website

Bowling Green, Kentucky travel guide from Wikivoyage

Bowling Green, Kentucky travel guide from Wikivoyage Geographic data related to Bowling Green, Kentucky at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Bowling Green, Kentucky at OpenStreetMap

На других языках

[de] Bowling Green (Kentucky)

Bowling Green ist die drittgrößte Stadt im US-Bundesstaat Kentucky. Laut United States Census Bureau hat die Stadt 72.294 Einwohner[1] (Stand: 2020).- [en] Bowling Green, Kentucky

[ru] Боулинг-Грин (Кентукки)

Бо́улинг-Грин (англ. Bowling Green) — американский город, административный центр округа Уоррен, штат Кентукки[1]. По состоянию на 2017 год, население города составляет 67 067 человек, что делает его третьим по численности в штате после Луисвилла и Лексингтона.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии