world.wikisort.org - Iran

Isfahan (Persian: اصفهان, romanized: Esfahân [esfæˈhɒːn] (![]() listen)), from its ancient designation Aspadana and, later, Spahan in middle Persian, rendered in English as Ispahan, is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Region, Isfahan Province, Iran. It is located 439.78 kilometres (273.27 miles) south of Tehran and is the capital of Isfahan Province.[5] The city has a population of approximately 2,220,000,[6] making it the third-largest city in Iran, after Tehran and Mashhad, and the second-largest metropolitan area.[7]

listen)), from its ancient designation Aspadana and, later, Spahan in middle Persian, rendered in English as Ispahan, is a major city in the Greater Isfahan Region, Isfahan Province, Iran. It is located 439.78 kilometres (273.27 miles) south of Tehran and is the capital of Isfahan Province.[5] The city has a population of approximately 2,220,000,[6] making it the third-largest city in Iran, after Tehran and Mashhad, and the second-largest metropolitan area.[7]

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

Isfahan

اصفهان Spahân, Aspadana | |

|---|---|

City | |

|

Top-bottom, R-L: Naqsh-e Jahan Square View from Qeysarie Gate Si-o-se-pol • Khaju Bridge Flower Garden of Isfahan • Chehel Sotoun Shah Mosque • Vank Cathedral | |

Flag  Seal  Coat of arms  Coat of arms/flag | |

| Nickname: Nesf-e Jahān (Half of the World) | |

Isfahan | |

| |

| Coordinates: 32°38′41″N 51°40′03″E | |

| Country | Iran |

| Province | Isfahan |

| County | Isfahan |

| District | Central |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ali Ghasemzade |

| • City Council | Mohammad Nour Salehi (Chairman) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 551 km2 (213 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,574 m (5,217 ft) |

| Population (2022 Census) | |

| • Urban | 2,219,343[2] |

| • Metro | 3,989,070[3] |

| • Population Rank in Iran | 3rd |

| Time zone | UTC+3:30 (IRST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+4:30 (IRDT 21 March – 20 September) |

| Area code | 031 |

| Climate | BWk[4] |

| Website | isfahan.ir |

| Isfahan city |

|---|

|

Isfahan is located at the intersection of the two principal routes that traverse Iran, north–south and east–west. Isfahan flourished between the 9th and 18th centuries. Under the Safavid dynasty, Isfahan became the capital of Persia, for the second time in its history, under Shah Abbas the Great. The city retains much of its history. It is famous for its Perso–Islamic architecture, grand boulevards, covered bridges, palaces, tiled mosques, and minarets. Isfahan also has many historical buildings, monuments, paintings, and artifacts. The fame of Isfahan led to the Persian proverb Esfahān nesf-e-jahān ast (Isfahan is half (of) the world).[8] Naqsh-e Jahan Square in Isfahan is one of the largest city squares in the world, and UNESCO has designated it a World Heritage Site.[9]

Etymology

Isfahan is derived from Middle Persian Spahān, which is attested to by various Middle Persian seals and inscriptions, including that of the Zoroastrian magi Kartir.[10] The present-day name is the Arabicized form of Ispahan (unlike Middle Persian, but similar to Spanish, New Persian does not allow initial consonant clusters such as sp[11]). The region is denoted by the abbreviation GD (Southern Media) on Sasanian coins. In Ptolemy's Geographia, it appears as Aspadana (Ἀσπαδανα), which translates to "place of gathering for the army". It is believed that Spahān derived from spādānām "the armies", the Old Persian plural of spāda, from which is derived spāh (𐭮𐭯𐭠𐭧) 'army' and spahi (سپاهی, 'soldier', literally 'of the army') in Middle Persian. Some of the other ancient names include Gey, Jey (old form Zi),[12] Park, and Judea.[13][14]

History

Human habitation of the Isfahan region can be traced back to the Palaeolithic period. Archaeologists have recently found artifacts dating back to the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic, Bronze, and Iron ages.

Bronze Age

What became the city of Isfahan likely emerged and gradually developed over the course of the Elamite civilisation (2700–1600 BCE).

Zoroastrian era

Under Median rule, a commercial entrepôt began to show signs of more sedentary urbanism, steadily growing into a noteworthy regional center that benefited from the exceptionally fertile soil on the banks of the Zayandehrud River, in a region called Aspandana or Ispandana.

When Cyrus the Great unified Persian and Median lands into the Achaemenid Empire, the religiously and ethnically diverse city of Isfahan became an early example of the king's fabled religious tolerance. It was Cyrus who, having just taken Babylon, made an edict in 538 BCE declaring that Jews in Babylon could return to Jerusalem.[15] Later, some of the freed Jews settled in Isfahan instead of returning to their homeland. The 10th-century Persian historian Ibn al-Faqih wrote:

When the Jews emigrated from Jerusalem, fleeing from Nebuchadnezzar, they carried with them a sample of the water and soil of Jerusalem. They did not settle until they reached the city of Isfahan, whose soil and water was deemed to resemble that of Jerusalem. Thereupon they settled there, cultivated the soil, raised children and grandchildren, and today the name of this settlement is Yahudia.[16]

The Parthians (247 BCE–224 CE), continued the tradition of tolerance after the fall of the Achaemenids, fostering a Hellenistic dimension within Iranian culture and the political organization introduced by Alexander the Great's invading armies. Under the Parthians, Arsacid governors administered the provinces of the nation from Isfahan, and the city's urban development accelerated to accommodate the needs of a capital city.

The next empire to rule Persia, the Sassanids (224 CE–651 CE), presided over massive changes in their realm, instituting sweeping agricultural reforms and reviving Iranian culture and the Zoroastrian religion. Both the city and region were then called by the name Aspahan or Spahan. The city was governed by a group called the Espoohrans, who descended from seven noble Iranian families. Extant foundations of some Sassanid-era bridges in Isfahan suggest that the Sasanian kings were fond of ambitious urban-planning projects. While Isfahan's political importance declined during this period, many Sassanid princes would study statecraft in the city, and its military role increased. Its strategic location at the intersection of the ancient roads to Susa and Persepolis made it an ideal candidate to house a standing army, which would be ready to march against Constantinople at any moment. The words "Aspahan" and "Spahan" are derived from the Pahlavi or Middle Persian meaning 'the place of the army'.[17]

Although many theories have mentioned the origins of Isfahan, little is known of it before the rule of the Sasanian dynasty. The historical facts suggest that, in the late 4th and early 5th centuries, Queen Shushandukht, the Jewish consort of Yazdegerd I (reigned 399–420), settled a colony of Jews in Yahudiyyeh (also spelled Yahudiya), a settlement 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) northwest of the Zoroastrian city of Gabae (its Achaemid and Parthian name; Gabai was its Sasanic name, which was shortened to Gay (Arabic 'Jay') that was located on the northern bank of the Zayanderud River (the colony's establishment was also attributed to Nebuchadrezzar, though that's less likely).[18] The gradual population decrease of Gay (Jay) and the simultaneous population increase of Yahudiyyeh and its suburbs, after the Islamic conquest of Iran, resulted in the formation of the nucleus of what was to become the city of Isfahan. The words "Aspadana", "Ispadana", "Spahan", and "Sepahan", all from which the word Isfahan is derived, referred to the region in which the city was located.

Isfahan and Gay were supposedly both circular in design, which was characteristic of Parthian and Sasanian cities.[19] However, this reported Sasanian circular city of Isfahan has not yet been uncovered.[20]

Islamic era

- Persian pottery from the city of Isfahan, 17th century

- Isfahan, capital of the Kingdom of Persia

- Si-o-se-pol Bridge by Cornelis de Bruijn, 1705

- Isfahan to the south side, drawing by Eugène Flandin

- Ali minaret, 1840, drawing by Eugène Flandin

- Russian army in Isfahan in the 1890s

When the Arabs captured Isfahan in 642, they made it the capital of al-Jibal ("the Mountains") province, an area that covered much of ancient Media. Isfahan grew prosperous under the Persian Buyid (Buwayhid) dynasty, which rose to power and ruled much of Iran when the temporal authority of the Abbasid caliphs waned in the 10th century. The city walls of Isfahan are thought to have been constructed during the tenth century.[21][22][23] The Turkish conqueror and founder of the Seljuq dynasty, Toghril Beg, made Isfahan the capital of his domains in the mid-11th century; but it was under his grandson Malik-Shah I (r. 1073–92) that the city grew in size and splendour.[24]

After the fall of the Seljuqs (c. 1200), Isfahan temporarily declined and was eclipsed by other Iranian cities, such as Tabriz and Qazvin. During his visit in 1327, Ibn Battuta noted that "The city of Isfahan is one of the largest and fairest of cities, but it is now in ruins for the greater part."[25]

In 1387, Isfahan surrendered to the Turko-Mongol warlord Timur. Initially treated with relative mercy, the city revolted against Timur's punitive taxes by killing the tax collectors and some of Timur's soldiers. In retribution, Timur ordered the massacre of the city residents, his soldiers killing a reported 70,000 citizens. An eye-witness counted more than 28 towers, each constructed of about 1,500 heads.[26]

Isfahan regained its importance during the Safavid period (1501–1736). The city's golden age began in 1598 when the Safavid ruler Abbas I of Persia (reigned 1588–1629) made it his capital and rebuilt it into one of the largest and most beautiful cities in the 17th-century world. In 1598, Abbas I moved his capital from Qazvin to the more central Isfahan. He introduced policies increasing Iranian involvement in the Silk Road trade.[27] Turkish, Armenian, and Persian craftsmen were forcefully resettled in the city to ensure its prosperity.[28] Their contributions to the economic vitality of the revitalized city supported the recovery of Safavid glory and prestige, after earlier losses to the Ottomans and Kızılbaş tribes,[28] ushering in a golden age for the city, when architecture and Persian culture flourished.

As part of Abbas's forced resettlement of peoples from within his empire, as many as 300,000 Armenians (primarily from Jugha) were resettled in Isfahan during Abbas' reign.[29][30])[30] In Isfahan, he ordered the establishment of a new quarter for these resettled Armenians from Old Julfa, and thus the Armenian Quarter of Isfahan was named New Julfa (today one of the largest Armenian quarters in the world).[29][30]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of deportees and migrants from the Caucasus settled in the city. Following an agreement between Shah Abbas I and his Georgian subject Teimuraz I of Kakheti ("Tahmuras Khan"), whereby the latter converted to Islam and submitted to Safavid rule in exchange for being allowed to rule as the region's wāli (governor), with his son serving as dāruḡa (prefect) of Isfahan.[31] He was accompanied by a troop of soldiers,[31] some of whom were Georgian Orthodox Christians.[31] The royal court in Isfahan had a great number of Georgian ḡolāms (military slaves), as well as Georgian women.[31] Although they spoke both Persian and Turkic, their mother tongue was Georgian.[31] Now the city had enclaves of those of Georgian, Circassian, and Daghistani descent.[31] Engelbert Kaempfer, who dwelt in Safavid Persia in 1684–85, estimated their number at 20,000.[31][32]

During Abbas's reign, Isfahan became famous in Europe, and many European travellers, such as Jean Chardin, gave accounts of their visits to the city. The city's prosperity lasted until it was sacked by Afghan invaders in 1722, during a marked decline in Safavid influence. Thereafter, Isfahan experienced a decline in importance, culminating in moving the capital to Mashhad and Shiraz during the Afsharid and Zand periods, respectively, until it was finally moved to Tehran, in 1775, by Agha Mohammad Khan, the founder of the Qajar dynasty.

In the early years of the 19th century, efforts were made to preserve some of Isfahan's archeologically important buildings. The work was started by Mohammad Hossein Khan, during the reign of Fath Ali Shah.[33]

Modern age

- Street from above

Isfahan in 1924

Isfahan in 1924- Foolad Mobarakeh Steel Mill

- Map of Isfahan by Pascal Coste

In the 20th century, Isfahan was resettled by many people from southern Iran: especially during the population migrations at the start of the century, and in the 1980s, following the Iran–Iraq War. During the war, 23,000 from Isfahan were killed; and there were 43,000 veterans.[34]

Today, Isfahan produces fine carpets, textiles, steel, handicrafts, and traditional foods, including sweets. Isfahan is noted for its production of the Isfahan rug, a type of Persian rug typically made of merino wool and silk. There are nuclear experimental reactors as well as uranium conversion facilities (UCF) for producing nuclear fuel in the environs of the city.[35] Isfahan has one of the largest steel-producing facilities in the region, as well as facilities for producing special alloys. The Mobarakeh Steel Company is the biggest steel producer in the whole of the Middle East and Northern Africa, and it is the biggest DRI producer in the world.[36] The Isfahan Steel Company was the first manufacturer of constructional steel products in Iran, and it remains the largest such company today.[37]

There is a major oil refinery and a large air-force base outside the city. HESA, Iran's most advanced aircraft manufacturing plant, is located just outside the city.[38][39] Isfahan is also attracting international investment.[40] Isfahan hosted the International Physics Olympiad in 2007. In 2020, the Iran-Qatar Joint Economic Commission met in the city.[41]

Geography

The city is located on the plain of the Zayandeh Rud (Fertile River) and the foothills of the Zagros mountain range. The nearest mountain is Mount Soffeh (Kuh-e Soffeh), just south of the city.

Hydrography

An artificial network of canals, whose components are called madi, were built during the Safavid dynasty for channeling water from Zayandeh Roud river into different parts of the city. Designed by Sheikh Bahaï, an engineer of Shah Abbas, this network has 77 madis in the northern course, and 71 in the southern course of the Zayandeh Rud. In 1993, this centuries-old network provided 91% of agricultural water, 4% of industrial needs, and 5% of city needs.[42] 70 emergency wells were dug in 2018 to avoid water shortages.[43][44][45]

Media related to Canals in Isfahan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Canals in Isfahan at Wikimedia Commons

Ecological issues

Towns and villages around Isfahan have been hit so hard by drought and water diversion that they have emptied out and people who lived there have moved.[46][47] An anonymous journalist said that what's called drought is more often the mismanagement of water.[48][49][50] The subsidence rate is dire, and the aquifer level decreases by one meter annually.[51] As of 2020, the city had the worst air quality between major Iranian cities.[52][53][54][55]

Flora and fauna

The Damask rose cultivar Rosa 'Ispahan' is named after the city.

Media related to Rosa Ispahan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rosa Ispahan at Wikimedia Commons

Cows endemic to Isfahan became extinct in 2020.[56]

Wagtails are often seen in farmlands and parks.[57]

The mole cricket is one of the major pests of plants, especially grass roots.[58][59]

Sheep and rams are symbols of Isfahan.[60]

Climate

| Esfahan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Situated at 1,590 metres (5,217 ft) above sea level on the eastern side of the Zagros Mountains, Isfahan has a cold desert climate (Köppen BWk). No geological obstacles exist within 90 kilometres (56 miles) north of the city, allowing cool winds to blow from this direction. Despite its altitude, Isfahan remains hot during the summer, with maxima typically around 35 °C (95 °F). However, with low humidity and moderate temperatures at night, the climate is quite pleasant. During the winter, days are cool while nights can be very cold. Snow falls an average of 6.7 days each winter.[61] However, generally Isfahan's climate is extremely dry. Its annual precipitation of 125 millimetres (4.9 in) is only about half that of Tehran or Mashhad and only a quarter that of more exposed Kermanshah.

The Zayande River starts in the Zagros Mountains, flowing from the west through the heart of the city, then dissipates in the Gavkhouni wetland. Planting olive trees in the city is economically viable, because such trees can survive water shortages.[62]

The highest recorded temperature was 43 °C (109 °F) on 11 July 2001 and the lowest recorded temperature was −19.4 °C (−3 °F) on 16 January 1996.

| Climate data for Isfahan (1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.8 (69.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

42.1 (107.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

42.0 (107.6) |

39.0 (102.2) |

33.2 (91.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

21.6 (70.9) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

22.7 (72.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

34.4 (93.9) |

36.8 (98.2) |

35.6 (96.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

17.0 (62.6) |

10.9 (51.6) |

23.5 (74.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

16.0 (60.8) |

21.1 (70.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

16.3 (61.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.1 (70.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

14.8 (58.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

9.1 (48.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −19.4 (−2.9) |

−12.2 (10.0) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−19.4 (−2.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 19.7 (0.78) |

15.5 (0.61) |

21.6 (0.85) |

19.9 (0.78) |

8.5 (0.33) |

1.2 (0.05) |

1.6 (0.06) |

0.3 (0.01) |

0.1 (0.00) |

3.7 (0.15) |

13.0 (0.51) |

19.9 (0.78) |

125 (4.91) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 3.9 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 3.6 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 23.5 |

| Average snowy days | 3.1 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 1.6 | 6.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 60 | 50 | 42 | 39 | 34 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 28 | 37 | 50 | 60 | 40 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 204.6 | 216.6 | 246.4 | 250.9 | 308.3 | 348.8 | 349.3 | 341.1 | 312.5 | 281.3 | 223.7 | 196.3 | 3,279.8 |

| Source: Iran Meteorological Organization (records),[63] (temperatures),[64] (precipitation),[65] (humidity),[66] (days with precipitation and snow),[67] (sunshine)[68] | |||||||||||||

Transportation

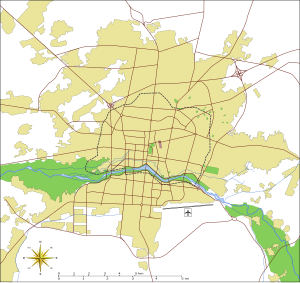

Roads and freeways

Over the past decade, Isfahan's internal highway network has been undergoing a major expansion. Much care has been taken to prevent damage to valuable, historical buildings. Modern freeways connect the city to Iran's other major cities, including the capital Tehran, 400 kilometres (250 mi) to the north, and Shiraz, 200 kilometres (120 mi) to the south. Highways also service satellite cities surrounding the metropolitan area.[69]

The Isfahan Eastern Bypass Freeway is under construction.

In 2021, a new AVL system was deployed in the city.[70][71][72]

Bridges

The bridges over the Zayanderud comprise some of the finest architecture in Isfahan. The oldest is the Shahrestan Bridge, whose foundations were built during the Sasanian Empire (3rd–7th century Sassanid era); it was repaired during the Seljuk period. Further upstream is the Khaju Bridge, which Shah Abbas II built in 1650. It is 123 metres (404 feet) long, with 24 arches; and it also serves as a sluice gate.

Another bridge is the Choobi (Joui) Bridge, which was originally an aqueduct to supply the palace gardens on the north bank of the river. Further upstream again is the Si-o-Seh Pol or bridge of 33 arches. It was built during the reign of Shah Abbas the Great by Sheikh Baha'i and connected Isfahan with the Armenian suburb of New Julfa. It is by far the longest bridge in Isfahan at 295 m (967.85 ft).

Another notable bridge is the Marnan Bridge.

Ride sharing

Snapp! and Tapsi[73][74] are two of the carpooling apps in the city.[75][76] The city has built 42 bicycle-sharing stations and 150 kilometres (93 mi) of paved bicycle paths.[77][78] As part of Iran's religious laws, women are forbidden to use the public bicycle-sharing network, as decreed by the representative of the Supreme Leader in Isfahan, Ayatollah Yousef Tabatabai Nejad, and General Attorney Ali Esfahani.[79]

Mass transit

The Isfahan and Suburbs Bus Company operates transit buses in the city. East-West BRT Bus Rapid Transit Line buses carry up to 120,000 passengers daily.[80]

The municipality has signed a memorandum with Khatam-al Anbiya to construct a tram network in the city.[81]

The Isfahan Metro was opened on 15 October 2015. It currently consists of one north–south line with a length of 11 kilometres (6.8 mi), and two more lines are currently under construction, alongside three suburban rail lines.[82]

The city is served by a railway station, with the Islamic Republic of Iran Railways running trains to Bandarabbas and Mashhad. The first high-speed railway in Iran, the Tehran-Qom-Isfahan line is currently being constructed and will connect Isfahan to Tehran and Qom.[83]

Airports

Isfahan is served by Isfahan International Airport, which in 2019 was the 7th busiest airport in Iran.[84][85]

Economy

In 2014, industry, mines, and commerce in Isfahan province accounted for 35% to 50% (almost $229 billion) of the Iranian Gross Domestic Product.[86][87] In 2019, Isfahan province's governorate said that tourism is the number one priority.[88]

According to Isfahan province's administrator for Department of Cooperatives, Labour, and Social Welfare, Iran has the cheapest labor workforce anywhere in the world; and this attracts foreign investors. The labor force has continually grown over the last three decades.[89][90] However, in 2018 the unemployment rate was 15%.[91]

The Esfahan Province Electricity Distribution Company, established in 1992, maintains a privatized power grid in the city.[92][93]

As of September 2020, the handicrafts industry of Isfahan Province was contributing $500 million annually to the economy.[94]

The municipality has implemented internet payment software.[95][96]

Isfahan Fair, a 22-hectare (54-acre) exhibition center aimed at increasing tourism, is under construction.

Aquaculture and agriculture

Isfahan city produces 1,300 tons of salmon. More than 28% of the country's ornamental fish is supplied from Isfahan province, from 780 farms, which in 2017 farmed 65.5 million fish.[97]

Opium was produced and exported from Isfahan from 1850 until it became illegal, and was an important source of income.[98] Isfahan has a large number of aqueducts, farmers having to divert water from the river to farms by canal.[99] Niasarm is one of the largest canals.[100] From 2012 to 2013 there were large protests by farmers against the Isfahan-Yazd water tunnel. In 2019, eastern city farmers demanded water, otherwise they would sabotage water transfer pipes.[101][102] Fruits and vegetables central market is where farmers sell their product wholesale, selling 10,000 tons a day.[103]

High tech and heavy industries

The industrialization of Isfahan dates from the Pahlavi period, as in all of Iran, and was marked by the strong growth of the textile industry, which earned the city the nickname "Manchester of Persia".[104] There are 9,200 industrial units in the city; 40% of the Iranian textile industry is in Isfahan.[105]

The Telecommunication Company of Iran and the Mobile Telecommunication Company of Iran provide 4G, 3G, broadband, and VDSL.[106][107]

The Isfahan Scientific and Research Town started in 2001, to act as a mediator between government, industry, and academia in establishing a knowledge-based economy.[108]

Isfahan is the third-largest medicine manufacturing hub in Iran.[109]

Recreation and tourism

In 2018–2019 some 450,000 foreign nationals visited the city. Some 110 trillion rials (over $2 billion at the official rate of 42,000 rials in 2020) have been invested in the province's tourism sector.[110]

Nazhvan Park hosts a reptile zoo with 40 aquariums.[111] There are the Saadi water park and the Nazhvan water park for children.[112][citation needed]

There are many luxury party gardens and wedding halls.[113][114][115]

Medical tourism

The Isfahan Healthcare city complex, built on a 300 hectares (740 acres) site near the Aqa Babaei Expressway, is intended to boost the city's medical tourism revenues.[116]

Shopping

The city is served by Refah Chain Stores Co., Iran Hyper Star, Isfahan City Center, Shahrvand Chain Stores Inc., Kowsar Market,[117] and the Isfahan Mall.

Cinemas

There are nine cinemas.[118] Historically, cinemas in old Isfahan were entertainment for the worker class while religious people considered cinema to be mostly an impure place and going to the cinema to be haram. During the 1979 revolution, many cinemas in Isfahan were burned down. Cinema Iran, now a ruin, was one of the oldest cinemas in the city. Great filmmakers such as Agnès Varda and Pier Paolo Pasolini shot scenes from their films in Isfahan.[119][120][121]

Sports

Isfahan has three association football clubs that play professionally. These are:

- Sepahan S.C.

- Zob Ahan Isfahan F.C.

- Sanaye Giti Pasand F.C.

- Polyacryl Esfahan F.C. (historic)

Sepahan has won the most league football titles among Iranian clubs (2002–03, 2009–10, 2010–11, 2011–12 and 2014–15).[122] The Foolad Mobarakeh Sepahan handball team plays in the Iranian handball league. Sepahan has a youth women running team that became national champions in 2020.[123]

Giti Pasand has a futsal team, Giti Pasand FSC, which is one of the best in Asia. They won the AFC Futsal Club Championship in 2012 and were runners-up in 2013. Giti Pasand also fields a women's volleyball team, Giti Pasand Isfahan VC, that plays matches in the Iranian Women's Volleyball League.[124]

Basketball clubs include Zob Ahan Isfahan BC and Foolad Mahan Isfahan BC.[125]

There are Pahlevani zoorkhanehs in the city.[126][127]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 60,000 | — |

| 1890 | 90,000 | +2.05% |

| 1900 | 100,000 | +1.06% |

| 1920 | 80,000 | −1.11% |

| 1933 | 100,100 | +1.74% |

| 1942 | 204,600 | +8.27% |

| 1956 | 254,700 | +1.58% |

| 1968 | 444,000 | +4.74% |

| 1976 | 671,800 | +5.31% |

| 1986 | 986,800 | +3.92% |

| 1991 | 1,182,735 | +3.69% |

| 1996 | 1,327,283 | +2.33% |

| 2001 | 1,502,567 | +2.51% |

| 2006 | 1,689,392 | +2.37% |

| 2011 | 1,853,293 | +1.87% |

| 2016 | 1,961,260 | +1.14% |

| source:[128] | ||

In 2019, the mean age for first marriages was 25 years for females and 30 years for males.[129][130]

There are almost 500,000 people living in slums, including in the northern part, and especially in the eastern sector of the city.[131]

Esfahani is one of the main dialects of Western Persian.[132][133] Jewish districts speak a unique dialect.[134]

Religion

There are many churches and synagogues in the city, with the churches being for the most part in New Julfa.

Mosques

- Agha Nour mosque (16th century)

- Hakim Mosque

- Ilchi mosque

- Jameh Mosque[135]

- Jarchi mosque (1610)

- Lonban mosque

- Maghsoudbeyk mosque (1601)

- Mohammad Jafar Abadei mosque (1878)

- Rahim Khan mosque (19th century)

- Roknolmolk mosque

- Seyyed mosque (19th century)

- Shah Mosque (1629) - It was damaged in 2022[136]

- Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque (1618)

Imamzadehs (shrine tombs)

- Imamzadeh Ahmad

- Imamzadeh Esmaeil and Isaiah mausoleum

- Imamzadeh Haroun-e-Velayat

- Imamzadeh Ja'far

- Imamzadeh Shah Zeyd

Churches and cathedrals

Churches are mostly located in the New Julfa region. The oldest is St. Jakob Church (1607). Some other historically important ones are St. Georg Church (17th century), St. Mary Church (1613), Bedkhem Church (1627), and Vank Cathedral (1664).

Pacifique de Provins established a French mission in the city in 1627.

Synagogues

- Kenisa-ye Bozorg (Mirakhor's kenisa)

- Kenisa-ye Molla Rabbi

- Kenisa-ye Sang-bast

- Mullah Jacob Synagogue

- Mullah Neissan Synagogue

- Kenisa-ye Keter David

Civic administration

Isfahan has a smart city program, a unified human resources administration system, and a transport system.[137][138][139][140][141]

In 2015, the comprehensive atlas of the Isfahan metropolis, an online statistical database in Farsi, was made available, to help in planning.[142][143][144]

In 2020, the municipality directly employed 6,250 people with an additional 3,000 people in 16 subsidiary organizations.[145]

In 2020, the municipality created a document outlining future development programs for the city.[146]

The color theme for the city has been turquoise for some time.[147]

Municipal government

The mayor is Ghodratollah Noroozi.[148]

The chairman of the city council is Alireza Nasrisfahani. There is also a leadership council within the city council.[149][150]

The representative of the Supreme Leader of Iran, as well as the representative from Isfahan in the Assembly of Experts, is Yousef Tabatabai Nejad.[151]

The city is divided into 15 municipal districts.

| Municipal districts of Isfahan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public works

City waste is processed and recycled at the Isfahan Waste Complex.[152]

The Isfahan Water and Sewage Company is responsible for piping water, waterworks installation and repair, maintaining sewage equipment, supervising sewage collection, and treatment and disposal of sewage in the city.[153][154]

Human resources and public health

As of June 2020, 65% of the population of Isfahan province has social security insurance.[155]

Isfahan is known as the Multiple sclerosis capital of the world due to the presence of polluting industries.[156]

In 2015, almost 15% of the people suffered from depression, from being cut off from the Zayandeh River, due to severe drought.[157]

Armed forces base

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Aerospace Force (IRGC AF) has an airbase in the city[158][85] and has undertaken a cloud seeding contract project using UAVs in Isfahan.[159] The Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force (IRIAF) has an airbase, the 8th Predator Tactical Fighter Base (TFB.8), which is the home base for Iranian F-14s.[160][161][162][163] The local Sepah Pasdaran is named "Master of the Era" ("Saheb al zaman" in Arabic and Farsi), after the Mahdi.[164] The Amir Al-Momenin University of Military Sciences and Technology is based in the city.

Education and science

The first elementary schools in the city were maktabkhanehs.[165][166][167][168] In World War II, Polish children sought refuge in the city; eight primary and technical trade schools were established. Between 1942 and 1945, approximately 2,000 children passed through, with Isfahan briefly gaining the nickname "City of Polish Children".[169][170] In 2019, there were 20 schools for trainees attended by 5,000 children.[171]

Notable schools

- Chahar Bagh School (early 17th century)

- Harati

- Kassegaran school (1694)

- Khajoo Madrasa

- Nimavar School (1691)

- Sadr Madrasa (19th century)

In total, there are more than 7,329 schools in Isfahan province.[172]

Colleges

In 1947, the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences was established; it now has almost 9,200 students and interns.[173] In 1973, the American School of Isfahan was built; it closed during the 1978–79 revolution. In 1974, the first technical university in Iran, the Isfahan University of Technology, was established in the city.[174] It focuses on science, engineering, and agriculture programs.[175] In 1977, the Isfahan University of Art was established. It was temporarily closed after the 1979 revolution, and was reopened in 1984, after the Iranian Cultural Revolution.[176]

Aside from seminaries and religious schools, the other public, private major universities of the Isfahan metropolitan area include: the Mohajer Technical And Vocational College of Isfahan, Payame Noor University, the Islamic Azad University of Isfahan, the Islamic Azad University of Najafabad, and the Islamic Azad University of Majlesi.

There are also more than 50 technical and vocational training centres in the province, under the administration of the Isfahan Technical and Vocational Training Organization (TVTO), that provide free, non-formal, workforce-skills training programs.[177] As of 2020, 90% of workforce-skills trainees are women.[178]

Notable philosophers

Major philosophers include Mir Damad, known for his concepts of time and nature, as well as for founding the School of Isfahan,[179] and Mir Fendereski, who was known for his examination of art and philosophy within a society.[180]

Culture

Ancient traditions included Tirgan, Sepandārmazgān festivals, and historically, men used to wear the Kolah namadi.[181][182]

The Isfahan School of painting flourished during the Safavid era.[183][184][185]

The annual Isfahan province theatre festival takes place in the city.[186] Theater performances began in 1919 (1297 AH), and currently there are 9 active theaters.[187][188][189]

The awarding of an Isfahan annual literature prize began in 2004.[190][191]

Since 2005, November 22 is Isfahan's National Day, commemorated with various events.[192]

New Art Paradise, built in District 6 in 2019, has the biggest open-air amphitheatre in the country.[193]

Based on a statue creators' symposium in 2020, the city decided to add 11 permanent art pieces to the city's monuments.[194]

The Isfahan international convention center is under construction.[195]

Cuisine

Gosh-e fil and Doogh are famous local snacks.[196][197] Other traditional breakfasts, desserts, and meals include Khoresht mast, Beryani, and meat with beans and pumpkin aush.[198][199][200][201][202][203][204] Gaz & Poolaki are two popular Iranian candies types that originated in Isfahan.

Teahouses are supervised and allowed to offer Hookah until 2022.[205] As of 2020, there are almost 300 teahouses with permits.[206]

Music

The Bayat-e Esfahan is one of the modes used in Iranian traditional music.

On 12 and 13 January 2018, the Iranian singer Salar Aghili performed in the city without the female members of his band, due to interference by local officials at the Ministry of Islamic Culture and Guidance.[207]

News media

During the Qajar era, Farhang, the first newspaper publication in the city, was printed for 13 years.[208] Iran's Metropolitan News Agency (IMNA), formerly called the Isfahan Municipality News Agency, is based in the city.[209]

The state-controlled Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting system (IRIB) has a TV network and radio channel in the city.[210]

Cultural sites

This article is in list format but may read better as prose. (October 2020) |

The city centre consists of an older section centered around the Jameh Mosque, and the Safavid expansion around Naqsh-e Jahan Square, with nearby palaces, bazaars, and places of worship,[211] which is called Seeosepol.[212]

Baths

Ancient baths include the Jarchi hammam and the bathhouse of Bahāʾ al-dīn al-ʿĀmilī; a public bath called "Garmabeh-e-shaykh" in Isfahan, which for many years was running and providing hot water to the public without any visible heating system which would usually need tons of wood, was built by Baha' al-din al-'Amili.[213][214][215][216] The Khosro Agha hammam was demolished by unknown persons in 1992. The Ali Gholi Agha hammam is another remaining bathhouse. Chardin writes that the number of baths in Isfahan in the Safavid era was 273.[217]

Bazaars

The Grand Bazaar, Isfahan, and its entrance, the Qeysarie Gate, were built in the 17th century. Social hubs were opium dens and coffeehouses clustered around the Chahar bagh and the Chehel Sotoun. The best-known traditional coffeehouse is Qahva-ḵāna-ye Golestān.[218][217][219][220][221][222] There is also the Honar Bazaar.

Cemeteries

The Bagh-e Rezvan Cemetery is one of the biggest and most advanced in the country.[223] Other cemeteries include the New Julfa Armenian Cemetery and the Takht-e Foulad.

Gardens and parks

The Pardis Honar Park, in District 6, has cost 30 billion toman as of 2018.[224] Some other zoological gardens and parks (including public and private beach parks, and non-beach parks) are: Birds Garden, Flower Garden of Isfahan, Nazhvan Recreational Complex, Moshtagh, Shahre royaha amusement park, and the East Park of Isfahan.[225]

Historical houses

- Alam's House

- Amin's House

- Malek Vineyard

- Qazvinis' House

- Sheykh ol-Eslam's House

- Constitution House of Isfahan

Mausoleums and tombs

- Al-Rashid Mausoleum (12th century)

- Baba Ghassem Mausoleum (14th century)

- Mausoleum of Safavid Princes

- Nizam al-Mulk Tomb (11th century)

- Saeb Mausoleum

- Shahshahan mausoleum (15th century)

- Soltan Bakht Agha Mausoleum (14th century)

Minarets

Menar Jonban was built in the 14th century. The tomb is an Iwan measuring 10 metres (33 ft) high.[226] Other menars include Ali minaret (11th century), Bagh-e-Ghoushkhane minaret (14th century), Chehel Dokhtaran minaret (12 century), Dardasht minarets (14th century), Darozziafe minarets (14th century), and Sarban minaret.

Museums

- Museum of Contemporary Art (17th-century building)

- Isfahan City Center museum (mall established 2012)

- Museum of Decorative Arts (1995)

- Natural History Museum of Isfahan (1988, 15th-century building)

Palaces and caravanserais

- Ali Qapu (Imperial Palace, early 17th century)

- Chehel Sotoun (Palace of Forty Columns, 1647)

- Hasht Behesht (Palace of Eight Paradises, 1669)

- Talar-e-Ashraf (Palace of Ashraf) (1650)

- Shah Caravanserai

Squares and streets

Other sites

International relations

There is a plan to create a diplomatic district next to the Imam Khamenei international convention center where foreign countries would locate their consulates.[81]

The Chinese have expressed readiness to be the first country that opens a consulate in a diplomatic zone in the central city.[236]

The building housing the General Consulate of the Russian Federation in Isfahan is a registered cultural heritage site.[237]

The residence of Afghan nationals is allowed in Isfahan city.

Since 1994, Isfahan has been a member of the League of Historical Cities and a full member of Inter-City Intangible Cultural Cooperation Network.[238][239]

The Isfahan municipality created a citizen diplomacy service program to boost establishing connections with sister cities around the world.[240][241][242][243]

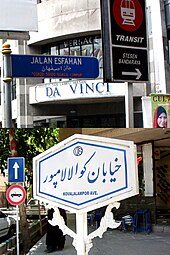

Twin towns – sister cities

Isfahan is twinned with:[244]

Baalbek, Lebanon (2010)

Baalbek, Lebanon (2010) Dakar, Senegal (2009)

Dakar, Senegal (2009) Florence, Italy (1998)

Florence, Italy (1998) Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany (2000)

Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany (2000) Havana, Cuba (2001)

Havana, Cuba (2001) Iași, Romania (1999)

Iași, Romania (1999) Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (1997)

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (1997) Kuwait City, Kuwait (2000)

Kuwait City, Kuwait (2000) Lahore, Pakistan (2004)

Lahore, Pakistan (2004) Saint Petersburg, Russia (2004)

Saint Petersburg, Russia (2004) Yerevan, Armenia (2000)

Yerevan, Armenia (2000) Xi'an, Shaanxi, China (1989)

Xi'an, Shaanxi, China (1989)

Cooperation agreements

Isfahan cooperates with:

In addition, the New Julfa quarter of Isfahan has friendly relations with:[247]

Issy-les-Moulineaux, France (2018)

Issy-les-Moulineaux, France (2018)

Notable people

This list of "famous" or "notable" persons has no clear inclusion or exclusion criteria. Please help to define clear inclusion criteria and edit the list to contain only subjects that fit those criteria. (October 2020) |

- Music

- Jalal Taj Esfahani (1903–1981)[248]

- Alireza Eftekhari (1956–), singer[249]

- Leila Forouhar (1959–), pop singer[250]

- Hassan Kassai (1928–2012), musician[251]

- Hassan Shamaizadeh, songwriter and singer[252]

- Jalil Shahnaz (1921–2013), tar soloist, a traditional Persian instrument[253]

- Film

- Rasul Sadr Ameli (1953–), director

- Sara Bahrami (1983–), actor[254]

- Homayoun Ershadi (1947–), Hollywood actor and architect

- Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari (1956–2001), the former princess of Iran and actress

- Bahman Farmanara (1942–), director

- Jahangir Forouhar (1916–1997), actor and father of Leila Forouhar (Iranian singer)

- Mohamad Ali Keshvarz (1930–2020), actor[255]

- Mahdi Pakdel (1980–), actor[256]

- Nosratollah Vahdat (1925–2020), actor[257]

- Craftsmen and painters

- Mahmoud Farshchian (1930–), painter and miniaturist[258]

- Bogdan Saltanov (1630s–1703), Russian icon painter of Isfahanian Armenian origin

- Political figures

- Ahmad Amir-Ahmadi (1906–1965), military leader and cabinet minister

- Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti (1928–1981), cleric, Chairman of the Council of Revolution of Iran[259]

- Nusrat Bhutto, Chairman of Pakistan Peoples Party from 1979 to 1983; wife of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto; mother of Benazir Bhutto

- Hossein Fatemi, PhD (1919–1954), politician; foreign minister in Mohamed Mossadegh's cabinet

- Mohammad-Ali Foroughi (1875–1942), a politician and Prime Minister of Iran in the World War II era[260]

- Dariush Forouhar (August 1928 – November 1998), a founder and leader of the Hezb-e Mellat-e Iran (Nation of Iran Party)

- Hossein Kharrazi, chief of the army in the Iran–Iraq War[261]

- Mohsen Nourbakhsh (1948–2003), economist, Governor of the Central Bank of Iran

- Mohammad Javad Zarif (1960–), Minister of Foreign Affairs and former Ambassador of Iran to the United Nations[262]

- Religious figures

- Lady Amin (Banou Amin) (1886–1983), Iran's most outstanding female jurisprudent, theologian and great Muslim mystic (‘arif), a Lady Mujtahideh

- Amina Begum Bint al-Majlisi was a female Safavid mujtahideh

- Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti (1928–1981), cleric, Chairman of the Council of Revolution of Iran[259]

- Allamah al-Majlisi (1616–1698), Safavid cleric, Sheikh ul-Islam in Isfahan

- Salman the Persian

- Muhammad Ibn Manda (d. 1005 / AH 395), Sunni Hanbali scholar of hadith and historian

- Abu Nu'aym Al-Ahbahani Al-Shafi'i (d. 1038 / AH 430), Sunni Shafi'i Scholar

- Seyyed Ali Qazi Askar (1954) Iran's supreme leader representative, in Haj

- Sportspeople

- Mohammad-Ali Asgari (1954–), Iranian football administrator

- Abdolali Changiz, football star of Esteghlal FC in the 1970s

- Mansour Ebrahimzadeh, former player for Sepahan FC, former head coach of Zobahan

- Ghasem Haddadifar, captain of Zobahan FC

- Arsalan Kazemi, forward for the Oregon Ducks men's basketball team and the Iran national basketball team

- Rasoul Korbekandi, goalkeeper of the Iranian National Team

- Moharram Navidkia, captain of Sepahan FC

- Mohammad Talaei, world champion wrestler

- Mahmoud Yavari (1939–), football player, coach of Iranian National Team

- Sohrab Moradi (1988–), Olympic weightlifting gold medalist, world record holder of 105 kg category

- Milad Beigi (1991–) Olympic taekwando bronze medalist, world champion

- Sina Karimian, K-1 cruiserweight kickboxing champion

- Writers and poets

- Mohammad-Ali Jamālzādeh Esfahani (1892–1997), author

- Hatef Esfehani, Persian Moral poet in the Afsharid Era

- Kamal ed-Din Esmail (late 12th century – early 13th century)

- Houshang Golshiri (1938–2000), writer and editor

- Hamid Mosadegh (1939–1998), poet and lawyer

- Mirza Abbas Khan Sheida (1880–1949), poet and publisher

- Saib Tabrizi

- Others

- Ispahani family, Perso-Bangladeshi business family

- Abd-ol-Ghaffar Amilakhori, 17th-century noble

- Adib Boroumand (1924–), poet, politician, lawyer, and leader of the National Front

- George Bournoutian, professor, historian, and author

- Jesse of Kakheti, king of Kakheti in eastern Georgia from 1614 to 1615

- Simon II of Kartli, king of Kartli in eastern Georgia from 1619 to 1630/1631

- David II of Kakheti, king of Kakheti in eastern Georgia from 1709 to 1722

- Constantine II of Kakheti, king of Kakheti in eastern Georgia from 1722 to 1732

- Nasser David Khalili (1945–), property developer, art collector, and philanthropist

- Arthur Pope (1881–1969), American archaeologist, buried near Khaju Bridge

- Alexandre de Rhodes (1591–1660), French Jesuit, designer of Vietnamese alphabet, buried in the city's Armenian cemetery

See also

- 15861 Ispahan

- Acid attacks on women in Isfahan

- Courts of Isfahan

- Isfahan National Holy Association

- Isfahan Seminary

- Islamic City Council of Isfahan

- List of the historical structures in the Isfahan province

- New Julfa

- Prix d'Ispahan

References

Citations

- [permanent dead link]

- "Esfahan Population 2022 (Demographics, Maps, Graphs)".

- "Major Agglomerations of the World - Population Statistics and Maps". citypopulation.de. 13 September 2018. Archived from the original on 13 September 2018.

- Shams, H. "Isfahan Climate". Iran Gazette. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- "Distance Tehran > Isfahan - Air line, driving route, midpoint". www.distance.to. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- "world population review". Archived from the original on 22 August 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- "اخبار راه آهن ایران: فهرست ایستگاههای راهآهن ایران". rail-news.ir. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- McKown, Robin (2 November 1975). "Isfahan Is Half The World". New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "Meidan Emam, Esfahan". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- "Isfahan, Pre-Islamic-Period". Encyclopædia Iranica. 15 December 2006. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Strazny, P. (2005). Encyclopedia of linguistics (p. 325). New York: Fitzroy Dearborn.

- "گاو، اسب و اینک اصفهان!". 13 March 2019.

- "وجه تسمیه اصفهان". daneshnameh.roshd.ir. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "::: سازمان تبلیغات اسلامی استان اصفهان :::". 8 May 2008. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- see Ezra ch. 1

- Gharipour Mohammad (14 November 2014). Sacred Precincts: The Religious Architecture of Non-Muslim Communities Across the Islamic World. Brill. p. 179.

- "Ishafan". ArchNet. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- "Esfahan | History, Art, Population, & Map". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 10 March 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- Jayyusi, Salma K.; Holod, Renata; Petruccioli, Attilio; André, Raymond (2008). The City in the Islamic World. Leiden: Brill. p. 174. ISBN 9789004162402.

- Huff, D. "Architecture iii. Sasanian Period". www.iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "City Walls of Isfahan". Archnet. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- Golombek, Lisa (1974). "Urban Patterns in Pre-Safavid Isfahan". Iranian Studies. 7 (1/2): 18–44. doi:10.1080/00210867408701454. ISSN 0021-0862. JSTOR 4310152.

- Isstaif, Abdul-Nabi (1997). "Review of Al-Muqaddasī: The Best Divisions for Knowledge of the Regions: Aḥsan al-Taqāsīm fī Ma'rifat al-Aqālīm". Journal of Islamic Studies. 8 (2): 247–250. doi:10.1093/jis/8.2.247. ISSN 0955-2340. JSTOR 26198094. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- "Britannica.com". Archived from the original on 23 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. p. 68. ISBN 9780330418799.

- Fisher, W.B.; Jackson, P.; Lockhart, L.; Boyle, J.A. : The Cambridge History of Iran, p. 55.

- Iskandaryan, Gohar (2019). "The Armenian community in Iran: Issues and emigration" (PDF). Global Campus Human Rights Journal. 3 (1): 129. ISSN 2532-1455. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. p. 41.

- Aslanian, Sebouh (2011). From the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean: The Global Trade Networks of Armenian Merchants from New Julfa. California: University of California Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0520947573.

- Bournoutian, George (2002). A Concise History of the Armenian People: (from Ancient Times to the Present) (2 ed.). Mazda Publishers. p. 208. ISBN 978-1568591414.

- "Isfahan vii. Safavid Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Matthee 2012, p. 67.

- Iran Almanac and Book of Facts. Vol. 8. Echo Institute. 1969. p. 71. OCLC 760026638. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "شهرداری اصفهان از طرح "خادمیاران شهدا" حمایت میکند - ایمنا". 9 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020.

- "Esfahan / Isfahan - Iran Special Weapons Facilities". fas.org. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "MSC at a Glance". Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- "Esfahan Steel Company A Pioneer in The Steel Industry of Iran". Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Hesaco.com Archived 9 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine (from the HESA official company website)

- Pike, John. "HESA Iran Aircraft Manufacturing Industrial Company". Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- "International conference held on investment opportunities in Iran tourism industry". Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- "Iran, Qatar Move to Broaden Economic Ties - Economy news". Tasnim News Agency. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Karimi, A.; Delavar, M. R. "Monitoring the Devastation of Isfahan Artificial Water Channels Using Remote Sensing and GIS" (PDF). The International Symposium on Spatio-Temporal Modeling ,2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- "حفر و تجهیز 70 حلقه چاه جدید برای جبران کمبود آب آشامیدنی اصفهان". kayhan.ir. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "اصفهان| خشکسالی پیدرپی در اصفهان چاههای فلمن را هم خشک کرد- اخبار استانها تسنیم - Tasnim". خبرگزاری تسنیم - Tasnim (in Persian). Archived from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Isfahan's Organic and Planned Form of Urban. Greenways in Safavid Period" (PDF). www.sid.ir. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- Kowsar, Nik; Nader, Alireza. "Iran Is Committing Suicide by Dehydration". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "Workers demand months of unpaid wages in 9 Iran protests". Iran News Wire. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Maxwell, Mary Jane (3 August 2018). "Iran arrests scientists trying to solve water crisis". ShareAmerica. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- Dehghanpisheh, Babak (29 March 2018). "Water crisis spurs protests in Iran". Reuters. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "اعتراضات جدید کشاورزان اصفهان به معضل کمآبی و حقآبه | صدای آمریکا فارسی". ir.voanews.com (in Persian). Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- وضعیت وخیم استان اصفهان در زیرِ زمین [Isfahan Province's Dire Status Underground]. IRIB News (in Persian). 3 October 2016. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- "هیچ کلانشهری در ایران به اندازه اصفهان آلوده نیست". Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Heydarian, Homeira (1 December 2016). اجرای طرح زوج و فرد خودروها تا پایان دی ماه ؛ اصفهان آلوده ترین روز سال ۹۹ را پشت سر گذاشت [Implementation of even and odd car plans until the end of January: Isfahan has passed the most polluted day of 1999]. Magiran (in Persian). Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- "کلاف سردرگم آلودگی هوای اصفهان و مقصرانی که زیربار نمیروند / منشأ آلودگی هوا کجاست؟ + فیلم". Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- "اینجا هوا کم است". Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- گاوهای بومی اصفهان منقرض شد / خطر در کمین بز و گوسفند بومی [Indigenous cattle of Isfahan have become extinct / Danger lurking for native goats and sheep]. 18 October 2020. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- پرندهای با دمجنبانزیبا [A beautiful bird with a lively tail!]. Isfahan-e-Ziba. 7 August 2019. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- "CAB Direct". Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- "Biological Control of Insect Parasitic Nematodes Using Grass" (PDF). New Ideas in Agriculture. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- "1 - Iran Travel, Trip to Iran". www.irangazette.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- "Isfahan, Iran - Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast". Weather Atlas. Yu Media Group. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "کاشت درخت زیتون در اصفهان صرفه اقتصادی دارد". ایمنا (in Persian). 4 October 2018. Archived from the original on 10 February 2019. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

-

- "Highest record temperature in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- "Lowest record temperature in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

-

- "Average Maximum temperature in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- "Average Mean Daily temperature in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- "Average Minimum temperature in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

-

- "Monthly Total Precipitation in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on March 30, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

-

- "Average relative humidity in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

-

- "No. Of days with precipitation equal to or greater than 1 mm in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- "No. of days with snow or sleet in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

-

- "Monthly total sunshine hours in Esfahan by Month 1951–2010". Iran Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- Assari, Ali; Erfan Assari (2012). "Urban spirit and heritage conservation problems: case study Isfahan city in Iran" (PDF). Journal of American Science. 8 (1): 203–209. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "گروه خبر / | پویش مردمی ترافیک شهر اصفهان". Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "Application of Smart AVL and AFC Systems in the Management and Utilization of the Bus Transit Network | Department of Transportation Engineering". Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- "سازمان سرمایه گذاری و مشارکتهای شهرداری اصفهان | شهردار اصفهان: سامانه های ( AVL ) و ( AFC ) پروژه های مشارکتی غیر مشهود اما پر اثر در حوزه حمل و نقل" (in Persian). Invest.isfahan.ir. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- "رانندگان تپسی : اینکرایهها نمیصرفد". Archived from the original on 5 June 2019.

- "تپسی در اصفهان فعال شد". ITIRAN | آی تی ایران (in Persian). 12 April 2017. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- "آمارهای اسنپ از سال 98". روزنامه دنیای اقتصاد (in Persian). Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "Snapp Taxi App Download | IOS & Andoid | Snapp Iran version of Uber". HI Tehran Hostel. 1 April 2019. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "واگنها جدید مترو در راه اصفهان/رفع مشکل ۲۵ ساله ناژوان در انتظار مصوبه شورای عالی شهرسازی". ایمنا (in Persian). 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- "تحول ۷۷۷ کیلومتری در شهر اصفهان". ایمنا (in Persian). 9 December 2020. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- "امام جمعه اصفهان: دوچرخه سواری زنان را ترویج نکنید / علما می گویند جایز نیست". 15 July 2020. Archived from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "تکمیل فاز نخست خط شرقی- غربی BRT اصفهان در آینده نزدیک". ایمنا (in Persian). 20 October 2020. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- "تبدیل مرکز همایشها به یک منطقه دیپلماتیک/ تراموا به اصفهان میآید". ایمنا (in Persian). 24 June 2020. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- "Esfahan metro opens". Railway Gazette. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- "China Finances Tehran-Isfahan High-Speed Railroad". Financial Tribune. 21 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- Iran Airports Company. 2019 Statistics (Report). گروه آمار و اطلاعات هوانوردی و فرودگاهی. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- "اصفهان - تاريخچه". isfahan.airport.ir. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "Statistical Center of Iran > Iran at a glance > Esfahan". Archived from the original on 16 November 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ۳۵ درصد تولید ناخالص ملی به استان اصفهان اختصاص دارد. 26 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- گردشگری اولویت اول استان اصفهان است [Tourism is the first priority of Isfahan province]. Isfahan Governorate (in Persian). 12 November 2019. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- "Isfahan xiv. Modern Economy and Industries". iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- "Isfahan xiv. Modern Economy and Industries". iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- دستمزد پایین کارگر در ایران باعث جذب سرمایهگذاران خارجی شده است. ایسنا (in Persian). 8 May 2019. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- معرفی شرکت [Introducing the Company]. Esfahan Province Electricity Distribution Company (EPEDC) (in Persian). Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- تاثیر مثبت نمایشگاه جدید اصفهان بر بهبود معیشت مردم. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- درآمد سالانه ۵۰۰ میلیون دلاری صنایع دستی استان اصفهان. ایمنا (in Persian). 30 September 2020. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- کیف پول الکترونیکی شهرداری اصفهان (اصکیف) رونمایی شد [Isfahan Municipality (ASKIF) e-wallet was unveiled]. Isfahan Mayor's Official Site (in Persian). Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- اصکیف-کیف-پول-شهرداری-اصفهان [Askif Wallet – City Hall, Isfahan]. Rasekhoon.net (in Persian). 2021. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- سهم استان اصفهان از تولیدات ماهی کشور در سال گذشته. ایمنا (in Persian). 23 December 2018. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "Afyūn". Encyclopedia Iranica. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 26 May 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- مادی های اصفهان، شریان زندگی - ایمنا. 7 February 2019. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- مادی پر آب نیاصرم؛ غصه دار زاینده رود. ایمنا (in Persian). 23 July 2016. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "Angry Farmers In Isfahan Sabotage Water Supply To Neighboring Yazd". 3 July 2021. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- کشاورزان معترض در نماز جمعه اصفهان به خطیب جمعه پشت کردند. 30 June 2020. Archived from the original on 30 June 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- معاون استاندار: میدان مرکزی میوه و ترهبار اصفهان نیازمند مدیریت مدرن است [Deputy governor: Isfahan fruit and vegetable center square needs modern management]. IRNA (in Persian). September–October 2019. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- "Newsletter" (PDF). Center for Iranian Studies–SIPA. Vol. 19, no. 1. Spring 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- صنعت نساجی اصفهان در تکاپوی بازگشت به عصر رونق [The textile industry of Isfahan is trying to return to the era of prosperity]. Tasnim News Agency (in Persian). 2019. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- افزایش پهنای باند اینترنت. ایمنا (in Persian). 27 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "یک میلیون پورت VDSL در اصفهان و قم راه اندازی می شود". 12 August 2020. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- خلاصه معرفی و تاریخچه. www.istt.org. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- دستاوردهای داروسازی؛ اصفهان قطب سوم داروسازی کشور [Pharmaceutical achievements; Isfahan is the third pharmaceutical hub of the country]. IRINN (in Persian). 6 September 2017. Archived from the original on 11 September 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Foreign arrivals in Isfahan rise sevenfold in 7 years". Tehran Times. 2 September 2020. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "باغ خزندگان اصفهان". Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- "Nazhvan Cultural & Recreational Resort | Esfahan, Iran Attractions". Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- بهترین باغ تالار عروسی اصفهان در سال 1400 [The best wedding hall garden in Isfahan in 1400]. Afraz Talar (in Persian). 20 August 2020. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- "فعالیت تالارهای اصفهان با رعایت دستورالعملهای بهداشتی". fa (in Persian). Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- "تخلف تالارهای پذیرایی در اصفهان/توقف مراسم عروسی با ۱۰۰۰ مهمان". ایمنا (in Persian). 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- "Promising Future for Isfahan Healthcare Hub". Financial Tribune. 22 August 2017. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- "راه اندازی سامانه خرید اینترنتی فروشگاههای کوثر اصفهان". fa (in Persian). Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- "برنامه سینماهای اصفهان". اصفهان امروز (in Persian). Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "سینما در اصفهانِ قدیم تفریح کارگران بود/ رابطهی معنادار میان ظهور و افول سینما با قدرت سیاسی و اقتصادی در اصفهان". خبرگزاری ایلنا (in Persian). Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- "تخریب قدیمی ترین سینمایی اصفهان؛ بازسازی یا تغییر کاربری". ایرنا (in Persian). 13 September 2018. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- "سينماهای قديمی اصفهان را از گنجه بيرون بياوريد". ایمنا (in Persian). 15 May 2011. Archived from the original on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- "گزارشی از تاریخ قهرمانان ایران؛ پرسپولیس بهترین تیم تاریخ، سپاهان برترین تیم لیگ/ یک آبی در صدر". Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "سپاهان قهرمان لیگ دوومیدانی زنان شد(عکس)". Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- "تیم گیتی پسند اصفهان قهرمان لیگ والیبال بانوان کشور شد/ راهیابی به مسابقات آسیایی - خبرگزاری مهر | اخبار ایران و جهان | Mehr News Agency". 8 June 2019. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- "سپاهان در بسکتبال تیمداری می کند". ایمنا (in Persian). 7 September 2020. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- "اصفهان نسبت به تهران بیشترین تعداد زورخانه را دارد- اخبار استانها تسنیم - Tasnim". خبرگزاری تسنیم - Tasnim (in Persian). Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- "5 زورخانه معروف اصفهان را بشناسید". روزنامه دنیای اقتصاد (in Persian). Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- "Iran: Provinces and Cities population statistics". Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "جوانان اصفهانی در هفتخان ازدواج". 6 August 2019. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- "سنازدواج در کدام شهرها بالاتر است؟". Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- "زنگ خطر آسیب های اجتماعی در مناطق حاشیه نشین نصف جهان". 9 February 2020. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Hammarström, Harald; et al. "Spoken L1 Language: Western Farsi". Glottolog. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- "پژوهشي رَوِشمند درگُستره يي زبان شناختي | Foundation for Iranian Studies". www.fis-iran.org. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- "Isfahan xix. Jewish Dialect". iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- "Isfahan Jame(Congregative) mosque – BackPack". Fz-az.fotopages.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- "Isfahan's Shah Mosque: Important Iranian site damaged in restoration - BBC News". Bbc.com. 13 August 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- "بزرگترین پروژه IT و شهر هوشمند در اصفهان آماده بهرهبرداری است". ایمنا (in Persian). 18 April 2021. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- "سیستم مدیریت یکپارچهسازی منابع انسانی اجرایی شد". ایمنا (in Persian). 12 May 2021. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- "به درگاه الکترونیکی شهرداری اصفهان - شهر هوشمند خوش آمدید | درگاه الکترونیکی شهرداری اصفهان - شهر هوشمند". smartcity.isfahan.ir. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- "اصفهان به برترین شهر هوشمند ایران تبدیل شود". ایمنا (in Persian). 22 September 2019. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- "پیش به سوی شهر هوشمند | اصفهان زیبا". isfahanziba.com. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- اطلس اصفهان. new.isfahan.ir (in Persian). Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- رونمايي از اطلس شهر اصفهان [Unveiling of the Atlas of Isfahan]. Iran's Metropolitan News Agency (IMNA) (in Persian). 27 August 2015. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- اطلس کلانشهر اصفهان را در پورتال شهرداری ببینید [See the Atlas of Isfahan metropolis on the municipal portal]. Iran's Metropolitan News Agency (IMNA) (in Persian). 9 December 2017. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- "لزوم توجه به هماهنگسازی حقوق و دستمزد در شهرداری اصفهان". ایمنا (in Persian). 19 July 2020. Archived from the original on 5 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "رویکرد نوین". برنامه جامع شهر اصفهان (in Persian). Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "تم رنگی اصفهان مشخص می شود". ایمنا (in Persian). 17 December 2015. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "قدرتالله نوروزی" شهردار اصفهان شد ["Ghodratollah Noroozi" became the mayor of Isfahan]. Tasnim News Agency (in Persian). August 2016. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "شورای راهبری". برنامه جامع شهر اصفهان (in Persian). Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "اعضای هیئت رئیسه شورای شهر اصفهان مشخص شدند/ نصراصفهانی رئیس ماند". 4 August 2020. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "نماینده ولی فقیه در استان اصفهان: تشكیل شورای رهبری، ایده صحیحی نیست". 20 December 2015. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- "تکمیل مجتمع پسماند اصفهان نیازمند ۵۰ میلیارد تومان تسهیلات است". 20 May 2020. Archived from the original on 15 June 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "About Us". Isfahan Water and Wastewater Company. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- "Responsibilities". Isfahan Water and Wastewater Company. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- "۶۵ درصد جمعیت استان اصفهان بیمه تأمین اجتماعی دارند". 29 August 2020. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "اصفهان پایتخت بیماری ام اس دنیا". 9 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "افسردگی 15 درصد اصفهانیها با خشکی زاینده رود | سایت انتخاب". 9 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "Khatami Air Base". GlobalSecurity.org. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "بارورسازی ابرها در 10 استان کشور با پهپاد- اخبار اقتصادی تسنیم - Tasnim". خبرگزاری تسنیم - Tasnim (in Persian). Archived from the original on 7 January 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- این موشک قدرتمند ایرانی آمریکایی ها را به وحشت انداخت + مشخصات و عکس [This powerful Iranian missile terrified the Americans + specifications and photos]. Donya-e-Eqtesad (in Persian). 17 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "The First Time the F-14 Tomcat Killed in Battle (But Not for America)". The National Interest. 12 June 2019. Archived from the original on 13 June 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Leone, Dario (8 July 2019). "Whoops: During the Iran-Iraq War, Baghdad Shot down an Iranian F-14A That Was Trying to Defect". The National Interest. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- انتصاب فرمانده پایگاه هشتم شکاری شهید بابایی اصفهان. www.iribnews.ir. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- مراسم معارفه فرمانده سپاه صاحب الزمان (عج) استان اصفهان به روایت تصاویر- اخبار اصفهان - اخبار استانها تسنیم - [The introductory ceremony of the commander of the Sahib al-Zaman Corps (AS) of Isfahan province, according to pictures - Isfahan News]. Tasnim News Agency. 9 September 2020. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- مکتبِ مکتبخانههای اصفهان | اصفهان زیبا. isfahanziba.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- مکتبخانه هاي قديم در اصفهان احياء مي شوند. old.ido.ir. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- در مکتبخانهها چه میگذشت؟. ایرنا (in Persian). 24 October 2020. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- آموزش و پرورش در ایران باستان. ایسنا (in Persian). 23 March 2020. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- "The life of Polish refugees in Iran seen through rare photographs , 1942-1945 - Rare Historical Photos". 8 December 2016.

- "The City of Polish Children". blogs.bl.uk.

- ۵۰۰۰ دانشآموز استثنایی اصفهان ۲۰ مدرسه استاندارد دارند! [5000 exceptional students of Isfahan have 20 standard schools!]. Iran's Metropolitan News Agency (IMNA). 28 May 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- "پایگاه مدارس استان اصفهان". old.roshd.ir. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "The University Campus | Isfahan University of Medical Sciences". english.mui.ac.ir. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "درباره دانشگاه | دانشگاه صنعتی اصفهان". www.iut.ac.ir. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "Isfahan University of Technology | Isfahan University of Technology". www.iut.ac.ir. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "درباره دانشگاه". aui.ac.ir. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "Isfahan Technical and Vocational Training Organisation". 8 October 2007. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- "اصفهان در گام نخست کسب عنوان پایتخت مهارت کشور". 8 July 2020. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- "Mir Damad, Muhammad Baqir (d. 1631)". www.muslimphilosophy.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Mri Fendereski". iranicaonline.org. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "آداب و رسوم مردم اصفهان". www.beytoote.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- "بهنام". www.ichodoc.ir. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- "آشنایی با مکتب اصفهان". همشهری آنلاین (in Persian). 12 July 2011. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- تبیان, موسسه فرهنگی و اطلاع رسانی. "مکتب اصفهان". article.tebyan.net (in Persian). Archived from the original on 17 April 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Reza, Khajeh Ahmad Attari Ali; Habibollah, Ayatollahi; Asghar, Shirazi Ali; Mohsen, Marasi; Khashayar, Ghazizadeh (1 January 2013). "The Study of Human Iconography in the Painting School of Isfahan 10-11/16-17". Motaleate Tatbighi Honar. 2 (4): 81–92. ISSN 2345-3842. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2022 – via Scientific Information Database.

- "از جشنوارۀ تئاتر اصفهان چه خبر؟". ایسنا (in Persian). 19 December 2020. Archived from the original on 19 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "تاریخچه تئاتر اصفهان". پایگاه خبری نمانامه (in Persian). 7 October 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "انسان شناسی و فرهنگ | انسانشناسی، علمیترین رشته علوم انسانی و انسانیترین رشته در علوم است". anthropology.ir. Archived from the original on 19 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "Iranian theaters" (PDF). Esfahan Theater. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.