world.wikisort.org - USA

New Iberia (French: La Nouvelle-Ibérie; Spanish: Nueva Iberia) is the largest city in and parish seat of Iberia Parish in the U.S. state of Louisiana.[2] The city of New Iberia is located approximately 21 miles (34 kilometers) southeast of Lafayette, and forms part of the Lafayette metropolitan statistical area in the region of Acadiana. The 2020 United States census tabulated a population of 28,555.[3] New Iberia is served by a major four lane highway, being U.S. 90 (future Interstate 49), and has its own general aviation airfield, Acadiana Regional Airport. Scheduled passenger and cargo airline service is available via the nearby Lafayette Regional Airport located adjacent to U.S. 90 in Lafayette.

New Iberia, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

City | |

| City of New Iberia | |

Downtown | |

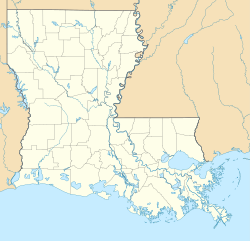

New Iberia Location in Louisiana  New Iberia New Iberia (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 30°0′13″N 91°49′6″W | |

| Country | United States |

| States | Louisiana |

| Parish | Iberia |

| Settled | 1779 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1839 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.25 sq mi (29.15 km2) |

| • Land | 11.14 sq mi (28.85 km2) |

| • Water | 0.11 sq mi (0.29 km2) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 28,555 |

| • Density | 2,563.06/sq mi (989.64/km2) |

| ZIP codes | 70560, 70562-70563 |

| FIPS code | 22-54035 |

| Website | www |

History

New Iberia dates its founding to the spring of 1779, when a group of some 500 colonists (Malagueños) from Spain, led by Lt. Col. Francisco Bouligny, came up Bayou Teche and settled around what became known as Spanish Lake.

The Spanish settlers called the town "Nueva Iberia" in honor of the Iberian Peninsula; French-speakers referred to the town as "Nouvelle Ibérie" while the English settlers arriving after the Louisiana Purchase called it "New Town." In 1814, the U.S. government opened a post office in the town, officially recognizing the name as New Iberia, but postmarks from 1802 show the town being called “Nova Iberia” (Latin for "new").[4] The town was incorporated as the "Town of Iberia" in 1839, but the state legislature amended the town's charter in 1847, recognizing New Iberia as the town's name.[5]

During the American Civil War, New Iberia was occupied by Union forces under General Nathaniel P. Banks. The soldiers spent the winter of 1862–1863 at New Iberia and, according to historian John D. Winters of Louisiana Tech University in his The Civil War in Louisiana, "found the weather each day more and more severe. The dreary days dragged by, and the men grumbled as they plowed through the freezing rain and deep mud in performing the regular routines of camp life."[6] Banks' men from New Iberia foraged for supplies in the swamps near the city.[7]

In 1868, Iberia Parish was established, and New Iberia became the seat of parish government. At first, only rented space served for the courthouse. State senator Samuel Wakefield and his family fled to New Orleans after their son was lynched by a white mob. By 1884 a new courthouse was completed on a landscaped lot in downtown New Iberia, at the present-day site of Bouligny Plaza. That courthouse served Iberia Parish until 1940. That year the current courthouse was built along Iberia Street, two blocks from the New Iberia downtown commercial district.

In September 2008, New Iberia was struck by Hurricane Ike. The lakes overflowed and filled the city, flooding it under several feet of dirty, brown water.[8]

Geography

New Iberia is located in southern Louisiana, in the Acadiana region. The city of New Iberia is a part of the Lafayette metropolitan area. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 10.6 square miles (27.4 km2), all land. In 2000, the population density was 3,088.8 people per square mile (1,192.8/km2). There were 12,880 housing units at an average density of 1,219.5 per square mile (470.9/km2). New Iberia lies approximately 16 to 20 feet above sea level.[9][10]

Among the lakes near the city is Lake Peigneur, which was formerly a 10-foot (3.0 m) deep freshwater lake until a 1980 disaster involving oil drilling and a salt mine. The lake is now a 1,300-foot (400 m) deep salt water lake, having been refilled by the Gulf of Mexico via the Delcambre Canal. There is also Lake Tasse, better known as Spanish Lake. This region has many natural features of interest, such as Avery Island, famous for its Tabasco sauce factory, deposits of rock salt, and Jungle Gardens.

Climate

New Iberia enjoys a sub-tropical climate with above average rainfall. As of 2021, annual average high temperature is 79 °F (26 °C) and the annual low is 59 °F (15 °C).[11]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 306 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,472 | — | |

| 1880 | 2,709 | 84.0% | |

| 1890 | 3,447 | 27.2% | |

| 1900 | 6,815 | 97.7% | |

| 1910 | 7,499 | 10.0% | |

| 1920 | 6,278 | −16.3% | |

| 1930 | 8,003 | 27.5% | |

| 1940 | 13,747 | 71.8% | |

| 1950 | 16,467 | 19.8% | |

| 1960 | 29,062 | 76.5% | |

| 1970 | 30,147 | 3.7% | |

| 1980 | 32,766 | 8.7% | |

| 1990 | 31,828 | −2.9% | |

| 2000 | 32,623 | 2.5% | |

| 2010 | 30,617 | −6.1% | |

| 2020 | 28,555 | −6.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 12,697 | 44.47% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 12,575 | 44.04% |

| Native American | 74 | 0.26% |

| Asian | 800 | 2.8% |

| Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.0% |

| Other/Mixed | 963 | 3.37% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,445 | 5.06% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 28,555 people, 11,030 households, and 7,338 families residing in the city. The 2019 American Community Survey estimated 29,456 people resided in the city limits.[14] At the 2010 U.S. census, the population of New Iberia was 30,617. At the census of 2000,[15] there were 32,623 people, 11,756 households, and 8,335 families residing in the city.

Of the population in 2019, New Iberians lived in 13,455 housing units; there were 11,030 households.[16] New Iberia's population had a sex ratio of 96.2 males per 100 females.[14] The city had a median age of 36.2 and 7,671 were under 18 years of age, 2,609 under 5 years, and 21,785 aged 18 and older. An estimated 4,268 households were married-couples living together, 784 cohabiting households, 2,273 male households with no female present, and 3,705 female households with no male present.[16] The average household size was 2.63 and the average family size was 3.24.

In 2000, there were 11,756 households, out of which 36.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.1% were married couples living together, 20.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.1% were non-families. 25.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.70 and the average family size was 3.24. In the city, the population was spread out, with 29.8% under the age of 18, 9.7% from 18 to 24, 26.8% from 25 to 44, 20.4% from 45 to 64, and 13.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.6 males.

The 2019 census estimates determined New Iberia a median income of $38,221 and mean income of $54,126.[17] At the 2000 census, the median income for a household in the city was $26,079, and the median income for a family was $30,828. Males had a median income of $30,289 versus $16,980 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,084. About 24.9% of families and 29.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 40.8% of those under age 18 and 20.8% of those age 65 or over.

Race and ethnicity

New Iberia had a racial and ethnic makeup of 51.6% non-Hispanic whites, 40.7% Blacks or African Americans, 0.1% American Indians and Alaska Natives, 1.4% Asian, 2.1% some other race, and 2.1% multiracial Americans. Hispanics or Latin Americans of any race made up 3.8% of the total population in 2019.[14] At the 2000 census, the racial makeup of the city was 56.99% White, 38.42% African American, 0.21% Native American, 2.64% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.51% from other races, and 1.20% from two or more races; 1.49% of the population were Hispanic or Latin American of any race.

Religion

In common with most of Louisiana, the majority of New Iberians profess a religion.[18] New Iberia is dominated by Christianity, and the single largest Christian denomination in the city is the Roman Catholic Church, owing in part to the Spanish and French heritage of its residents. Catholics in New Iberia and the surrounding area are served by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Lafayette in Louisiana.[19] Of the religious population, 0.1% each practice Judaism or an eastern religion.

Economy

The city of New Iberia was the founding headquarters for Bruce Foods before their relocation to Lafayette; it was also the birthplace of Trappey's Hot Sauce. Currently, the economy is stimulated by small businesses, agriculture, New Iberia station, Louisiana Hot Sauce, and Acadiana Regional Airport.

Arts and culture

Places of interest

- Shadows-on-the-Teche historic former residence and plantation, now owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[20]

- The Bayou Teche Museum has exhibits on the history, culture, artists and industries of the Bayou Teche region. Location of artist George Rodrigue's last studio.[21]

- Avery Island, home of Tabasco sauce and claims to be the oldest salt mine in North America. In operation since 1862.[22]

- Jungle Gardens, botanical garden and bird sanctuary located in Avery Island.[23]

- Jefferson Island is a former salt mine, botanical garden, rookery, nursery, as well as the historic Victorian Joseph Jefferson House.[24]

- Conrad Rice Mill is on the National Register of Historic Places, oldest rice mill in operation since 1912, offering public tours.[25]

- The city used to hold a statue of the Roman emperor, Hadrian. It was located on the corner of Weeks and St. Peter Streets, until approx. 2008 when it was sold.[26]

Festivals

New Iberia hosts the Louisiana Sugar Cane Festival in September.[27] The Sugar Cane Festival celebrates the commencement of the sugar cane harvest, locally referred to as grinding. Sugar cane is a principal crop grown by New Iberia farmers. The city also hosts El Festival Español de Nueva Iberia, which honors the area's Spanish heritage.[28] Other notable festivals include the World Championship Gumbo Cook-Off, on the second full weekend in October;[29] and the Books Along the Teche Literary Festival, in April, which celebrates James Lee Burke and South Louisiana literature.[30]

Popular culture

New Iberia is home to fictional detective Dave Robicheaux and his creator, author James Lee Burke.[31] In the Electric Mist, a movie based on one of Burke's novels, was filmed in New Iberia in 2009 and starred Tommy Lee Jones.

Education

Public schools

Iberia Parish School System serves the city and parish area.

High schools

- New Iberia Senior High School

- Westgate High School

Middle schools

- Anderson Middle School

- Belle Place Middle School

- Iberia Middle School

Elementary schools

- Belle Place Elementary

- Caneview Elementary

- Center Street Elementary

- Coteau Elementary

- Daspit Elementary

- Jefferson Island Road Elementary

- John Hopkins Elementary

- Magnolia Elementary

- North Lewis Elementary

- North Street Elementary

- Park Elementary

- Pesson Elementary

- Sugarland Elementary

Private schools

- Acadiana Christian School is a private Nondenominatinal K-12 School in New Iberia.[32]

- Catholic High School (of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Lafayette in Louisiana) is a private Catholic high school in New Iberia.

- Highland Baptist Christian School is a private Baptist K-12 school in New Iberia.[33]

Colleges and universities

Iberia Parish is in the service area of Fletcher Technical Community College and of South Louisiana Community College.[34]

Notable people

This is a list of notable people from New Iberia, Louisiana. It includes people who were born/raised in, lived in, or spent portions of their lives in New Iberia, or for whom New Iberia is a significant part of their identity. This list is in order by career and in alphabetical order by last name.

Actors

- Joseph Jefferson, artist and stage actor, portrayed the role of Rip Van Winkle and built the Jefferson Mansion as a hunting lodge on Jefferson Island in 1870.[35]

- Yvonne Levy Kushner, French-Jewish American actress, socialite and philanthropist, born in New Iberia.[36]

Authors and journalists

- James Lee Burke, novelist, mystery writer.

- Glenn R. Conrad, author, professor, and historian of south Louisiana culture, a native of New Iberia.[37]

- Louis Lautier, the first African-American journalist admitted in 1955 to the White House Correspondents' Association,[38] born in New Iberia.[39]

Artists and designers

- Jamie Baldridge, artist, photographer, arts educator, writer.[40] Born and raised in New Iberia.

- Rosa Lee Brooks, artist, blues singer, arts educator, performer.[41] Born in New Iberia and raised in Los Angeles, California.[40]

- William Eckart, set designer for film, stage and television,[42] born in New Iberia.

- Alyce Frank, Southwestern landscapes painter born in New Iberia.[43]

- William Weeks Hall, painter and photographer; between the 1920s and 1950s he restored his family's historic home, the Shadows-on-the-Teche plantation.[44]

- George Rodrigue, artist and creator of the Blue Dog series of paintings

- Owen Southwell, architect, and native of New Iberia.[45]

Business

- William Dore, businessman, political donor, founder of Global Industries, Ltd., born and raised in New Iberia.[46]

- Paul Fleming, restaurateur and founder of P.F. Chang's Chinese Bistro, Fleming's Prime Steakhouse, Paul Martin's American Bistro and others, born in New Iberia.[47]

- Bryan Lourd, Partner, managing director and co-chairperson of CAA

Politics and civil service

- Taylor Barras, state representative for District 48; Speaker of the Louisiana House of Representatives , effective January 11, 2016

- Kathleen Blanco, former Governor of Louisiana from 2004 to 2008

- Edwin S. Broussard, U.S. senator from 1921 to 1933

- Robert F. Broussard, U.S. representative from 1897 to 1915 and U.S. senator from 1915 to 1918

- Patrick T. Caffery, attorney, member of the Louisiana House of Representatives from 1964 to 1968 and U.S. Representative from 1969 to 1973.

- W. Eugene Davis, U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge from 1983 until present.

- John Duhe, U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge from 1988 to 2011.

- Ted Haik, state representative from Iberia, St. Mary, and Vermilion parishes (1976–96); current New Iberia city attorney

- Billy Hewes, Mississippi politician

- Wilbert J. Le Melle, American diplomat, author and academician, United States Ambassador to the Republic of Kenya and United States Ambassador to the Republic of the Seychelles from 1977 to 1980, deputy representative for East and Central Africa of the Ford Foundation from 1970 to 1973.[48] Born in New Iberia.[48]

- Jeff Landry, attorney and Republican member of the United States House of Representatives (2011–12) Attorney General-State of Louisiana 2016–present.

Music

Sports

- Kermit Alexander, defensive back (San Francisco 49ers, 1963–69)

- Jon Emminger, professional wrestler working for WWE as Lucky Cannon

- Howie Ferguson, NFL player (Green Bay Packers, 1953–58)

- Damon Harrison, NFL player, former New York Jets player, currently with New York Giants

- Johnny Hector, running back (New York Jets, 1983–92)

- Willie Hector, NFL player

- Kerry Joseph, CFL quarterback

- Jared Mitchell, outfielder for the Chicago White Sox

- Mark Roman, NFL defensive back, played 2000–2003 with Cincinnati Bengals, 2004–2005 with Green Bay Packers, and 2006–2009 with San Francisco 49ers.

- Diontae Spencer, CFL wide receiver and return specialist, born in New Iberia.[51]

- Tyrunn Walker, NFL defensive lineman, former New Orleans Saints player, currently a free agent.

- Corey Raymond, cornerback for the NY Giants; LSU Defensive Backs Coach, Nebraska secondary coach.

Science

- Norman F. Carnahan, chemical engineer[52]

Sister cities

| City | Division | Country | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alhaurín de la Torre | [53] | ||

| Fuengirola | |||

| Saint-Jean-d'Angély | [54] | ||

| Woluwe-Saint-Pierre | |||

See also

- Louisiana Hot Sauce – a hot sauce brand manufactured in New Iberia

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Iberia Parish, Louisiana

References

- "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "QuickFacts: New Iberia city, Louisiana". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Kopersmith, Van, ed. (2016). "American Stampless Cover Catalog: Louisiana" (PDF). Indianapolis, Indiana: U.S. Philatelic Classics Society. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- "East Main Street Historic District - New Iberia, LA - U.S. National Register of Historic Places". Waymarking. April 4, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963; ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 300

- Winters, p. 237

- "2008- Hurricane Ike". Hurricanes: Science and Society. Retrieved 2018-01-08.

- "Map New Iberia - Louisiana Longitude, Altitude - Sunset". U.S. Climate Data. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "New Iberia, Iberia, United States on the Elevation Map. Topographic Map of New Iberia, Iberia, United States". Elevation Map. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Climate Data for New Iberia, Louisiana". U.S. Climate Data. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved 2021-12-29.

- "2019 American Community Survey Population Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "2019 Selected Characteristic Estimates for New Iberia". U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "2019 Income Characteristics for New Iberia". U.S. Census Bureau. 2019. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Religion in New Iberia, Louisiana". Sperling's BestPlaces. 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "South Deanery". Roman Catholic Diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- "The Shadows". The Shadows. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- firefly-wp. "Bayou Teche Museum - New Iberia, Louisiana". Bayou Teche Museum. Retrieved 2021-08-05.

- "Avery Island". NESTA. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- "Jungle Gardens". City of New Iberia, Louisiana. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- "Jefferson Island". Iberia Parish Convention & Visitors Bureau. 25 September 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- "Konriko Rice Mill and Company Store". Conrad Rice Mill. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Leleux-Thurbon, Holly (December 3, 2008). "Hadrian statue ready for sale". The Daily Iberian. iberianet.com.

- "HiSugar | Louisiana Sugar Cane Festival". Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- "El Festival Espanol de Nueva Iberia". Iberia Travel. 9 May 2017. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "World Championship Gumbo Cookoff | Greater Iberia Chamber of Commerce". iberiachamber.org. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- "Books Along the Teche Literary Festival | New Iberia LA – Celebrating New Iberia, Dave Robicheaux's Hometown, and Great Southern Writers". Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- tgg-staff (2012-09-19). "James Lee Burke". Iberia Travel. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- "About". Acadiana Christian School. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Home". Highland Baptist Christian School. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "Our Colleges". Louisiana's Technical and Community Colleges. Retrieved 2021-06-03.

- "Jefferson Island History | New Iberia, LA". Rip Van Winkle Gardens. Retrieved 2021-08-06.

- "Yvonne Levy Kushner Obituary". Washington Post. 1990-02-09. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- "Living Legends: Glen Conrad". The Acadian Museum. Retrieved 2019-02-11.

- Kelly, John (2017-07-05). "Perspective, Remembering when politicians didn't seem to hate journalists quite so much". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- "The World Today". The Pittsburgh Courier. May 19, 1962. p. 1. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- Bookhardt, D. Eric (2008-04-03). "Image Conscious". Gambit. Retrieved 2018-02-15.

- https://rosaleebrooks.com/.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "The Press: Color Bar". Time Magazine. 1955-01-31. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- "Legends of Fine Art | Alyce Frank - Southwest Art Magazine". Southwest Art Magazine. 1970-01-01. Retrieved 2018-02-15.

- "William Weeks Hall Has A Final Resting Place At The Shadows". Newspapers.com. The Daily Advertiser. 27 June 1961. p. 9. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Owen J. Southwell Papers". Edith Garland Dupré Library. University of Louisiana at Lafayette. 2014-10-13. Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- "2016 Louisiana Legends Honorees". Louisiana Public Broadcasting. 2016. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- Farkas, David; Ramos, Bethany. "Conceptual Thinking: P.F. Chang's Founder Forges Ahead in Restaurant Innovation". BuyerZone. BuyerZone.com, LLC. A Purch Brand. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- "Jimmy Carter: United States Ambassador to Kenya and Seychelles - Nomination of Wilbert J. Le Melle". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- "Bunk Johnson". Know Louisiana. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities at Turners' Hall. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- "Eulis 'Soko' Richardson Obituary". The Daily Iberian. 2004-02-06. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- "Diontae Spencer". Ottawa Redblacks. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "Norman Carnahan". Acadian Museum. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- Celine (2015-10-19). "New Iberia's Spanish Twinning: A Spaniard's Perspective". Iberia Travel. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- Brégowy, Philippe (13 January 2016). "Saint-Jean-d'Angély : pas d'hibernation pour les jumelages". SudOuest.fr (in French). Retrieved 2021-05-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to New Iberia, Louisiana. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article "New Iberia". |

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии