world.wikisort.org - USA

Boyle Heights, historically known as Paredón Blanco,[2][3][4] is a neighborhood in Los Angeles, California, located east of the Los Angeles River. It is one of the city's most notable and historic Chicano/Mexican-American communities and is known as a bastion of Chicano culture, hosting cultural landmarks like Mariachi Plaza and events like the annual Día de los Muertos celebrations.[5]

Boyle Heights | |

|---|---|

Neighborhood of Los Angeles | |

|

Top: Mariachi Plaza; St. Mary's Church; bottom: Calvary Church; LAC+USC Medical Center. | |

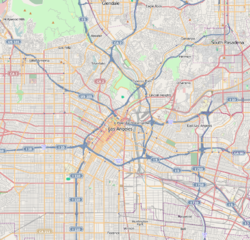

Boundaries of Boyle Heights as drawn by the Los Angeles Times | |

Boyle Heights Location within Los Angeles | |

| Coordinates: 34.03389°N 118.20444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Los Angeles |

| City | Los Angeles |

| Government | |

| • City Council | Kevin de León (D) |

| • State Assembly | Miguel Santiago (D) |

| • State Senate | Maria Elena Durazo (D) |

| • U.S. House | Jimmy Gomez (D) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6.5 sq mi (17 km2) |

| Population (2000)[1] | |

| • Total | 92,785 |

| • Density | 14,262/sq mi (5,507/km2) |

| ZIP Codes | 90023, 90033, 90063 |

| Area code(s) | 213/323 |

History

Boyle Heights was called Paredón Blanco ("White Bluff") during the Spanish, Mexican, and early American periods.[6] During Mexican rule, what would become Boyle Heights became home to a small settlement of relocated Tongva refugees from the village of Yaanga in 1845.[7] The villagers were relocated to this new site known as Pueblito after being forcibly evicted from their previous location on the corner Alameda and Commercial Street by German immigrant Juan Domingo (John Groningen), who paid Governor Pío Pico $200 for the land.[8]

On August 13, 1846, Los Angeles was seized by invading American forces during the Mexican–American War.[9] Under American occupation, Indigenous elimination became a core principal of governance and the Pueblito site was razed to the ground in 1847: "the Indians were required to live in dispersed settlements or with their employers in the city."[8] The destruction of Pueblito was reportedly approved by the Los Angeles City Council and largely displaced the final generation of the villagers, known as Yaangavit, into the Calle de los Negros ("place of the dark ones") district.[10]

The area became named after Andrew Boyle, an Irishman born in Ballinrobe, who purchased 22 acres (8.9 ha) on the bluffs overlooking the Los Angeles River after fighting in the Mexican–American War for $4,000.[11] Boyle established his home on the land in 1858. In the 1860s, he began growing grapes and sold the wine under the “Paredon Blanc” name.[12] His son-in-law William Workman served as early mayor and city councilman and also built early infrastructure for the area.[13]

From 1889 through 1909 the city was divided into nine wards. In 1899 a motion was introduced at the Ninth Ward Development Association to use the name Boyle Heights to apply to all the highlands of the Ninth Ward, including Brooklyn Heights and Euclid Heights.[14] XLNT Foods had a factory making tamales here early in their history. The company started in 1894, when tamales were the most popular ethnic food in Los Angeles. The company is the oldest continuously operating Mexican food brand in the United States, and one of the oldest companies in Southern California.[15]

In the early 1910s, Boyle Heights was one of the only communities that did not have restricted housing covenants that discriminated against Japanese and other people of color.[16] The Japanese community of Little Tokyo continued to grow and extended to the First Street Corridor into Boyle Heights in the early 1910s.[17] Boyle Heights became Los Angeles’s largest residential communities of Japanese immigrants and Americans, apart from Little Tokyo. In the 1920s and 1930s, Boyle Heights became the center of significant churches, temples, and schools for the Japanese community. These include the Tenrikyo Junior Church of America, the Konko Church, and the Higashi Honganji Buddhist Temple; all designed by Yos Hirose. The Japanese Baptist Church was built by the Los Angeles City Baptist Missionary Society.[18] A hospital, also designed by Hirose, opened in 1929 to serve the Japanese American community.[19]

By the 1920s through the 1960s,[20] Boyle Heights was racially and ethnically diverse as a center of Jewish, Mexican and Japanese immigrant life in the early 20th century, and also hosted significant Yugoslav, Armenian, African-American and Russian populations.[21][22] Bruce Phillips, a sociologist who tracked Jewish communities across the United States, said that Jewish families left Boyle Heights not because of racism, but instead because of banks redlining the neighborhood (denying home loans) and the construction of several freeways through the community.[23]

In 1961, the construction of the East LA Interchange began. At 135 acres in size, the interchange is three times larger than the average highway system, even expanding at some points to 27 lanes in width.[24] The interchange handles around 1.7 million vehicles daily and has produced one of the most traffic congested regions in the world as well as one of the most concentrated pockets of air pollution in America.[24] Since the 1920s, both elite and working-class communities throughout Southern California have witnessed the enforcement of highly effective racial covenants and other exclusionary measures that aim to distinguish separate white and non-white neighborhoods. This resulted in the development of Boyle Heights, a multicultural, interethnic neighborhood in East Los Angeles whose celebration of cultural difference has made it a role model for democracy.[24]

In 2017, some residents were protesting gentrification of their neighborhood by the influx of new businesses,[25] a theme found in the TV series Vida and Gentefied, both set in the neighborhood.[26]

Demographics

As of the 2000 census, there were 92,785 people in the neighborhood, which was considered "not especially diverse" ethnically,[27] with the racial composition of the neighborhood at 94.0% Latino, 2.3% Asian, 2.0% White (non-Hispanic), 0.9% African American, and 0.8% other races. The median household income was $33,235, low in comparison to the rest of the city. The neighborhood's population was also one of the youngest in the city, with a median age of just 25.[1]

As of 2011, 95% of the community was Hispanic and Latino. The community had Mexican Americans, Mexican immigrants, and Central American ethnic residents. Hector Tobar of the Los Angeles Times said, "The diversity that exists in Boyle Heights today is exclusively Latino".[23]

Latino communities These were the ten cities or neighborhoods in Los Angeles County with the largest percentage of Latino residents, according to the 2000 census:[28]

- East Los Angeles, California, 96.7%

- Maywood, California, 96.4%

- City Terrace, California, 94.4%

- Huntington Park, California, 95.1%

- Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, 94.0%

- Cudahy, California, 93.8%

- Bell Gardens, California, 93.7%

- Commerce, California 93.4%

- Vernon, California, 92.6%

- South Gate, California, 92.1%

Latino political influence

The emergence of Latino politics in Boyle Heights influenced the diversity in the community. Boyle Heights was a predominantly Jewish community with "a vibrant, pre-World War II, Yiddish-speaking community, replete with small shops along Brooklyn Avenue, union halls, synagogues and hyperactive politics ... shaped by the enduring influence of the Socialist and Communist parties"[29] before Boyle Heights became predominantly associated with Mexicans/Mexican Americans. The rise of the socialist and communist parties increased the people's involvement in politics in the community because the "liberal-left exercised great influence in the immigrant community".[29]: 22-23 Even with an ever-growing diversity in Boyle Heights, "Jews remained culturally and politically dominant after World War II".[29]: 22

Nevertheless, as the Jewish community was moving westward into new homes, the largest growing group, Latinos, was moving into Boyle Heights because to them this neighborhood was represented as upward mobility. With Jews and Latinos both in Boyle Heights, these men, part of the Jewish Community Relations Council (JCRC) — Louis Levy, Ben Solnit, Pinkhas Karl, Harry Sheer, and Julius Levitt — helped to empower the Latinos who either lived among the Jewish people or who worked together in the factories.

The combination of Jewish people and Latinos in Boyle Heights symbolized a tight unity between the two communities. The two groups helped to elect Edward R. Roybal to the City Council over Councilman Christensen; with the help from the Community Service Organization (CSO). In order for Roybal to win a landslide victory over Christensen, "the JCRC, with representation from business and labor leaders, associated with both Jewish left traditions, had become the prime financial benefactor to CSO .. labor historically backed incumbents ... [and] the Cold War struggle for the hearts and minds of minority workers also influenced the larger political dynamic".[29]: 26

In the 1947 election, Edward Roybal lost, but Jewish community activist Saul Alinsky and the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) garnered support from Mexican Americans to bring Roybal to victory two years later 1949.[30](Bernstein, 243) When Roybal took office as city councilman in 1949, he experienced racism when trying to buy a home for his family. The real-estate agent told him that he could not sell to Mexicans, and Roybal's first act as councilman was to protest racial discrimination and to create a community that represented inter-racial politics in Boyle Heights.[30](Bernstein, 224).

This Latino-Jewish relationship shaped politics in that when Antonio Villaraigosa became mayor of Los Angeles in 2005, "not only did he have ties to Boyle Heights, but he was elected by replicating the labor-based, multicultural coalition that Congressman Edward Roybal assembled in 1949 to become Los Angeles's first city council member of Latino heritage".[29]: 23 Further, the Vladeck Center (named after Borukh Charney Vladeck) contributed to the community of Boyle Heights in a big way because it was not just a building, it was "a venue for a wide range of activities that promoted Jewish culture and politics".[29]: 22

Government and infrastructure

The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services operates the Central Health Center in Downtown Los Angeles, serving Boyle Heights.[31]

The United States Postal Service's Boyle Heights Post Office is located at 2016 East 1st Street.[32]

The Social Security Administration[33] is located at 215 North Soto Street Los Angeles, CA 90033 1-800-772-1213

Transportation

Boyle Heights is home to four stations of the LA Metro:

Education

Just 5% of Boyle Heights residents aged 25 and older had earned a four-year degree by 2000, a low percentage for the city and the county. The percentage of residents in that age range who had not earned a high school diploma was high for the county.[34]

Public

- SIATech Boyle Heights Independent Study, Charter High School, 501 South Boyle Avenue

- Extera Public School, Charter Elementary, 1942 E. 2nd Street and 2226 E. 3rd Street

- Extera Public School #2, Charter Elementary, 1015 S. Lorena Street

- Francisco Bravo Medical Magnet High School, alternative, 1200 North Cornwell Street

- Theodore Roosevelt High School, 456 South Mathews Street

- Mendez High School 1200 Playa Del Sol

- Animo Oscar De La Hoya Charter High School, 1114 South Lorena Street

- Boyle Heights Continuation School, 544 South Mathews Street* Central Juvenile Hall, 1605 Eastlake Avenue

- Hollenbeck Middle School, 2510 East Sixth Street

- Robert Louis Stevenson Middle School, 725 South Indiana Street

- KIPP Los Angeles College Preparatory, charter middle, 2810 Whittier Boulevard

- Murchison Street Elementary School, 1501 Murchison Street

- Evergreen Avenue Elementary School, 2730 Ganahl Street

- Sheridan Street Elementary School, 416 North Cornwell Street

- Malabar Street Elementary School, 3200 East Malabar Street

- Breed Street Elementary School, 2226 East Third Street

- First Street Elementary School, 2820 East First Street

- Second Street Elementary School, 1942 East Second Street

- Soto Street Elementary School, 1020 South Soto Street

- Euclid Avenue Elementary School, 806 Euclid Avenue

- Sunrise Elementary School, 2821 East Seventh Street

- Utah Street Elementary School, 255 Gabriel Garcia Marquez Street

- Bridge Street Elementary School, 605 North Boyle Avenue

- Garza (Carmen Lomas) Primary Center, elementary, 2750 East Hostetter Street

- Christopher Dena Elementary School, 1314 Dacotah Street

- Learning Works Charter School, 1916 East First Street

- Lorena Street Elementary School, 1015 South Lorena Street

- PUENTE Learning Center, 501 South Boyle Avenue

- East Los Angeles Occupational Center (Adult Education), 2100 Marengo Street[35]

- Endeavor College Preparatory Charter School, 1263 S Soto St, Los Angeles, CA 90023

Private

- Bishop Mora Salesian High School, 960 South Soto Street

- Santa Teresita Elementary School, 2646 Zonal Avenue

- Assumption Elementary School, 3016 Winter Street

- Saint Mary Catholic Elementary School, 416 South Saint Louis Street

- Our Lady of Talpa, elementary, 411 South Evergreen Avenue

- East Los Angeles Light and Life Christian School, 207 South Dacotah Street

- Santa Isabel Elementary School, 2424 Whittier Boulevard

- Dolores Mission School, elementary, 170 South Gless Street

- Cristo Viene Christian School, 3607 Whittier Boulevard

- Resurrection, elementary, 3360 East Opal Street

- White Memorial Adventist School, 1605 New Jersey Street

- PUENTE Learning Center, 501 South Boyle Avenue

Landmarks

Existing

- Breed Street Shul, which was declared a historic-cultural monument in 1988[36]

- Self-Help Graphics and Art, the first community-based organization in the country to create a free public celebration of Day of the Dead

- Los Angeles County+USC Medical Center/Keck School of Medicine of USC

- Los Angeles County Department of Coroner

- Estrada Courts Murals

- Evergreen Cemetery

- Hazard Park

- Mariachi Plaza

- Hollenbeck Park

- Linda Vista Community Hospital (Now Hollenbeck Terrace Apartments, former Santa Fe Coast Lines Hospital)

- Sears Building, Olympic Boulevard and Soto St.

- Malabar Public Library

- Lucha Underground Temple, where the television program Lucha Underground is taped.[37][38]

- St. Mary's Catholic Church (4th and Chicago Streets)

Demolished

- Soto-Michigan Jewish Community Center[39]

- Aliso Village

- Sisters Orphan Home, operated by Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, 917 S. Boyle Ave. demolished due to earthquake damage and construction of freeway[40]

Notable people

Politics

- Sheldon Andelson, first openly gay person to be appointed to the University of California Regents or any high position in state government[41]

- Hal Bernson, Los Angeles City Council member, 1979–2003[42]

- Martin V. Biscailuz, attorney and Common Council member, 1884–85[43][44]

- Howard E. Dorsey, City Council member, 1937[45]

- Oscar Macy, county sheriff and member of the Board of Supervisors[46]

- Edward R. Roybal, Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives for the 30th District and later for the 25th District of California; member of the Los Angeles City Council[47]

- Winfred J. Sanborn, City Council member, 1925–29[48]

- Antonio Villaraigosa, Mayor of Los Angeles[49]

- Zev Yaroslavsky, Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, 3rd District[50]

Sports

Crime

- Mickey Cohen, gangster[55]

Arts and culture

- Oscar Zeta Acosta, attorney, writer, community activist[56]

- Lou Adler, record producer, manager[57]

- Herb Alpert[58]

- Greg Boyle, Catholic priest, community activist[59][60]

- Norman Granz[61]

- Josefina López, writer[62]

- Anthony Quinn, actor[63]

- Andy Russell, international singing star[64]

- Julius Shulman, photographer[65]

- Taboo, rapper[66]

- will.i.am, recording artist and music producer[67][68]

Publishing

- Jack T. Chick, publisher of Chick tracts[69]

In popular culture

- 1917: Nuts in May[70]

- 1957: The Pajama Game[71][72]

- 1979: Boulevard Nights

- 1980: The Other Side of the Bridge (Spanish: Del Otro Lado del Puente)

- 1987: Born in East L.A.[citation needed]

- 1992: American Me[citation needed]

- 1993: Blood In Blood Out

- 1995: Dangerous Minds

- 1998–2009 Breaking the Magician's Code: Magic's Biggest Secrets Finally Revealed

- 2007: Under the Same Moon[73]

- 2008: The Take[74]

- 2011: A Better Life[73]

- 2014–present: Lucha Underground[38]

- 2015: East LA Interchange (documentary)[75]

- 2015/2016: No más bebés

- 2018–2020: Vida

- 2020–2021: Gentefied

- 2021: Night Teeth

See also

- List of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments on the East and Northeast Sides

- List of districts and neighborhoods in Los Angeles

References

- "Los Angeles Times Neighborhood Project". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 16, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- "Neighborhoods: Exploring the rich history and culture of Boyle Heights". KPCC - NPR News for Southern California - 89.3 FM.

- Anacapa:A society Upon a Place and Time

- "Water and Power Associates".

- Los Angeles Times Boyle Heights: Problems, Pride, and Promise

- George J. Sanchez (2004). "What's Good for Boyle Heights is Good for the Jews: Creating Multiculturalism on the Eastside during the 1950s". American Quarterly. 56 (3): 663–661. doi:10.1353/aq.2004.0042. S2CID 144365105.

- Estrada, William David (2009). The Los Angeles Plaza: Sacred and Contested Space. University of Texas Press. p. 56. ISBN 9780292782099.

In June 1845 this last remnant of Yaanga was relocated across the Los Angeles River to present-day Boyle Heights. Following the United States' takeover of Los Angeles, Indians continued to cluster along the edge of the pueblo.

- Morris, Susan L.; Johnson, John R.; Schwartz, Steven J.; Vellanoweth, Rene L.; Farris, Glenn J.; Schwebel, Sara L. (2016). The Nicoleños in Los Angeles: Documenting the Fate of the Lone Woman's Community (PDF). Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. pp. 94–97.

- Ríos-Bustamante, Antonio. Mexican Los Ángeles: A Narrative and Pictorial History, Nuestra Historia Series, Monograph No. 1. (Encino: Floricanto Press, 1992), 50–53. OCLC 228665328.

- Kudler, Adrian Glick (April 27, 2015). "Finding Yaangna, the Ancestral Village of LA's Native People". Los Angeles Curbed.

- Vigeland, Tess (March 14, 2013). "Neighborhoods: Exploring the rich history and culture of Boyle Heights". Take Two. KPCC. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- Morrison, Patt (November 1, 2022). "Long before citrus reigned in Southern California, L.A. made wine. Lots of it". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- Los Angeles's Boyle Heights. Japanese American National Museum: Arcadia Publishing. 2005. p. 11. ISBN 9780738530154.

- "What's in a Name? Ninth Ward Citizens Vote in Favor of Boyle Heights". Los Angeles Herald. May 24, 1899. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- Arellano, Gustavo (December 23, 2019). "The XLNT tamales go back 125 years, capturing nostalgia for Californians across the U.S." Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- Watanabe, Teresa (February 22, 2010). "Boyle Heights celebrates its ethnic diversity". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- "Japanese American Heritage". The Los Angeles Conservancy. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- "LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Japanese Americans in Los Angeles, 1869-1970" (PDF). Survey LA. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 22, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- Agrawal, Nina (January 4, 2020), "Japanese Hospital — symbol of defiance of racism — honored in Boyle Heights", Los Angeles Times, archived from the original on March 24, 2020, retrieved April 26, 2020

- "East LA Interchange: A Documentary Exploration of Boyle Heights - ProQuest". search.proquest.com. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- Reyes-Velarde, Alejandra (February 22, 2020). "Spanish-language newsstand, a 1940s Boyle Heights gem, braces for the end". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

...Boyle Heights went from a true polyglot melting pot of Mexican, Jewish, Italian, Eastern European, Japanese and other people to one of L.A.'s capitals of Mexican American culture.

- Cheng, Cheryl (May 25, 2021). "New digital exhibit explores Jewish history in Boyle Heights". UCLA. Archived from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- Tobar, Hector. "A look back at the Boyle Heights melting pot Archived 2011-12-10 at the Wayback Machine." Los Angeles Times. December 9, 2011. Retrieved on December 10, 2011.

- Estrada, Gilbert (October 2005). "If You Build It, They Will Move: The Los Angeles Freeway System and the Displacement of Mexican East Los Angeles, 1944-1972". Southern California Quarterly. 87 (3): 287–315. doi:10.2307/41172272. ISSN 0038-3929. JSTOR 41172272.

- Ruben Vives (July 18, 2017). "A community in flux: Will Boyle Heights be ruined by one coffee shop?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 9, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017.

- Lloyd, Robert (February 20, 2020). "No matter where you live, you'll relate to Netflix's L.A. gentrification comedy". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- Archived 2013-10-22 at the Wayback Machine Diversity "measures the probability that any two residents, chosen at random, would be of different ethnicities. If all residents are of the same ethnic group it's zero. If half are from one group and half from another it's .50." —Los Angeles Times

- "Latino" Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times

- Burt, Kenneth (May–June 2008). "Yiddish Los Angeles and the Birth of Latino Politics" (PDF). Jewish Currents. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- The Community Service Organization (CSO) helped Roybal win the election and to increase the multi-racial involvement in Boyle Heights.

- "Central Health Center Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine." Los Angeles County Department of Health Services. Retrieved on March 18, 2010.

- "Post Office Location - BOYLE HEIGHTS." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on December 7, 2008.

- "File Not Found - Social Security Administration". www.ssa.gov. Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ""Boyle Heights," Mapping L.A., Los Angeles Times". Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2013.

- "Welcome to east LA service area". Archived from the original on November 9, 2014.

- The City Project. "Historic - Cultural Monuments (HCM) Listing" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- Suarez, Lucia. "Mexican Lucha Libre gets American face time in new El Rey Network drama series". Fox News. Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- Queally, James (April 22, 2015). "Learn to speak lucha: The secret language of the squared circle". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- Tugend, Tom (March 10, 2006). "Boyle Heights JCC". Jewish Journal. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- Spitzzeri, Paul R. (November 7, 2011) "The Los Angeles Orphans' Asylum" Archived 2015-02-24 at the Wayback Machine Boyle Heights History Blog

- Roderick, Kevin (December 30, 1987). "Andelson Dies of AIDS; Gay Regent, Activist". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- Hayes, Dade (April 24, 1997). "Reward Offered in Sexual Assault Case". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 4, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- "Finding Aid of the Eugene Biscailuz scrapbooks 0216". www.oac.cdlib.org. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- "An Unofficial Guide to Los Angeles County Law Enforcement and Fire Department History Through Photos, Badges, and Patches". Archived from the original on August 11, 2012.

- Los Angeles Public Library reference file Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine This file was compiled in 1937 by Works Progress Administration worker Clare Wallace from an interview with Dorsey on June 23 of that year and from newspaper articles.

- Now part of North Cummings Street. Archived 2013-05-08 at the Wayback Machine Location of the Oscar Macy home here on Mapping L.A.

- "Southland Mourns Death of Edward Roybal". ABC-7 News. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- Devin Carroll, Brian Carroll and Wayne Raymond, Winfred and Mamie Sanborn (privately printed)

- Rebecca Spence (February 20, 2008). "L.A.'s Latino Mayor Welcomed as One of the Tribe". The Jewish Daily Forward. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- Klein, Amy (May 9, 2003). "Aliyah Perspectives". Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- "Games People Play: A Press Photo of Track and Field Star Lillian Copeland, Los Angeles, 21 May 1926". The Homestead Blog. May 22, 2020.

- "PASSINGS: Bill Harmatz". January 29, 2011. Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2019 – via Los Angeles Times.

- "How Three Jews Behind the AFL Invented the Modern Media Spectacle That is Pro Football Today". Tablet Magazine. February 3, 2011. Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- "Franz Lidz, "Up and Down in Beverly Hills," Sports Illustrated, April 17, 2000". Archived from the original on July 8, 2010. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- Tereba, Tere (2012). Mickey Cohen: The Life and Crimes of L.A.'s Notorious Mobster. ECW Press. ISBN 9781770902039.

- Martinez, Yoli (October 2, 2012). "Iconic Hispanic Angelenos in History: Oscar Zeta Acosta". KCET Departures. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013.

- David Kamp "Live at the Whisky" Archived 2013-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

- HAITHMAN, DIANE (March 15, 1998). "Herb Alpert's Brass Rings". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- Stark, Ray (May 12, 1993). "Father Boyle and Gangs". Letter to the Editor. Los Angeles Times. Beverly Hills. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- Mejia, Brittny (November 4, 2015). "Great Read: After 30 years of helping gang members, Father Greg Boyle is slowing a bit but still determined". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 23, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2019.

- John Thurber "Norman Granz, 83; Visionary of the Jazz World Was Producer, Promoter and Social Conscience" Archived 2013-10-23 at the Wayback Machine, "Los Angeles Times" November 24, 2001

- "Biography | Josefina Lopez". Archived from the original on February 17, 2015. Retrieved May 16, 2013. Lopez website

- "Actor - LifeChums: Be Chums 4 Life - Page 2". Archived from the original on April 20, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- Loza, Steven (1993). Barrio Rhythm: Mexican American Music in Los Angeles. University of Illinois Press. p. 148.

- Mary Melton, "Lens Master" Archived 2013-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, "Los Angeles Magazine" Jan 1, 2009

- Taboo; Steve Dennis (February 8, 2011). Fallin' Up: My Story. Touchstone. pp. 1, 3–4. ISBN 978-1-4391-9206-1.

- Dennis, Steve; Taboo (2011). Fallin' Up: My Story. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 56. ISBN 9781439192085. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- Will.i.am on Living in East Los Angeles | Exclusive Interview | NELA TV (Web video). Los Angeles, CA: egentertainment.net. February 17, 2011. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- "Jack Chick - Christian Comics Pioneer". www.christiancomicsinternational.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

- Ted Okuda, James L. Neibaur "Stan Without Ollie: The Stan Laurel Solo Films, 1917-1927" Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine, McFarland, 2012

- David Parkinson "The Rough Guide to Film Musicals" Archived 2016-11-30 at the Wayback Machine, Rough Guides, 2007

- "The Pajama Game (1957) - IMDb". Archived from the original on June 3, 2019. Retrieved September 19, 2017 – via www.imdb.com.

- "Hollywood Depicts Latinos Solely In Stereotypes". The Huffington Post. April 11, 2012. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved January 8, 2016.

- "The Take". September 12, 2007. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved April 5, 2014 – via www.imdb.com.

- Israel, Ira (October 21, 2015). ""East LA Interchange": Film Review". HuffPost. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

Further reading

- "Jewish American Heritage". The Los Angeles Conservancy. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- Boyle Heights: How a Los Angeles Neighborhood Became the Future of American Democracy. George F. Sanchez. Berkeley: Univ. of Calif. Press, 2021. ISBN 9780520237070

External links

- Boyle Heights Neighborhood Council

- Boyle Heights Beat

- Self Help Graphics & Art

- CASA 1010 Theater

- Boyle Heights: Power of Place

- History of Aliso Village

- Breed Street Shul Project, Inc.

- Boyle Heights Learning Collaborative

- Boyle Heights Historical Society

- Comments about living in Boyle Heights

- Boyle Heights crime map and statistics

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии